There’s a multibillion marketing practice in the pharmaceutical industry known as “detailing” in which representatives visit physicians’ offices to share information about their company’s newest drug in hopes of convincing them to prescribe it. While the practice has its critics, it’s been an effective way of boosting drug sales.

And now a Stanford researcher who has spent years examining the marketing practices of the pharmaceutical industry says it might be time for the National Institutes of Health to consider funding an independent form of “detailing” to educate physicians about treatments for which there is clear evidence of benefit for their patients.

Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, is the lead author of a study published today in the Archives of Internal Medicine on the subject. He and his colleagues examined a highly regarded 2002 clinical trial (known as the ALLHAT study) in which researchers determined that thiazide-type diuretics should be the initial drug of choice for reducing high blood pressure. Stafford said the diuretics are low-cost medication that have been on the market for years and have a good safety profile. However, many physicians and patients often incorrectly believe newer, costlier medications to be better than the old standbys.

To determine whether an educational effort would persuade physicians to follow the ALLHAT guidelines, Stafford and his colleagues analyzed an NIH-funded “academic detailing” effort in which 147 trained representatives made presentations to small groups of practitioners on the blood-pressure recommendations.

The result was that in the areas where the academic detailing effort was the most intense, prescriptions for the diuretics increased as much as 8.6 percent compared to areas where there was little or no educational outreach.

“The bottom line is that it made a difference, but it was a modest effect,” Stafford said. “It’s a testament to how difficult it is to change these physician practices, even when we have what seems like overwhelming evidence.”

With all of the money that the NIH spends on research, Stafford said he thinks it would be worth a further investment to make sure that physicians are prescribing drugs that are beneficial and cost-effective for their patients.

“Without academic detailing, clinical trials will have a suboptimal impact on physician prescribing patterns,” Stafford said. “But if you are going to do it, you need to put enough resources into the process to reach physicians, convince them that the data are reliable and help them change their prescribing patterns.”

Photo by Steve Fisch Photography

I was speaking recently with a friend who, concerned about his father’s health, accompanied his dad to the doctor’s office. The doctor asked his dad how he felt, and the dad replied that everything was fine. That seemed to satisfy the doctor until my friend spoke up, pointing out the weakness in one of his father’s arms as well as increased memory problems. Why wasn’t the doctor better able to spot the father’s problems during multiple visits in recent months, my friend wondered?

I was speaking recently with a friend who, concerned about his father’s health, accompanied his dad to the doctor’s office. The doctor asked his dad how he felt, and the dad replied that everything was fine. That seemed to satisfy the doctor until my friend spoke up, pointing out the weakness in one of his father’s arms as well as increased memory problems. Why wasn’t the doctor better able to spot the father’s problems during multiple visits in recent months, my friend wondered?

Science education isn’t faring well in many U.S. high schools, with American teenagers being outperformed by their counterparts in several other developed countries. But universities and colleges might be able to help change that.

Science education isn’t faring well in many U.S. high schools, with American teenagers being outperformed by their counterparts in several other developed countries. But universities and colleges might be able to help change that.

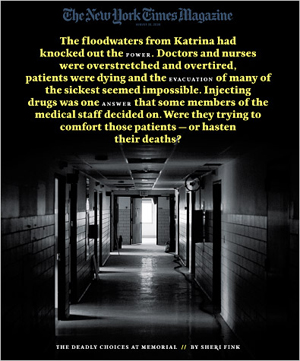

Four years after Hurricane Katrina hit the New Orleans area, Stanford medical school alum

Four years after Hurricane Katrina hit the New Orleans area, Stanford medical school alum