Ask Stanford Med: Director of Stanford Autism Center taking questions on research and treatment

on May 8th, 2013 No Comments

Among school-aged children in the United States an estimated one in 50 has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, according to a recent survey (.pdf) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition to raising concerns among researchers and parents about why the number of cases has increased, the findings underscored the need to do more autism research and to provide support and services for families caring for autistic children.

Among school-aged children in the United States an estimated one in 50 has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, according to a recent survey (.pdf) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition to raising concerns among researchers and parents about why the number of cases has increased, the findings underscored the need to do more autism research and to provide support and services for families caring for autistic children.

To help parents and others in the local community better understand the growing prevalence of autism and to learn about treatments and research advancements, the Stanford Autism Center at Packard Children’s Hospital will host its sixth annual Autism Spectrum Disorders Update on June 1. The event offers an opportunity for exchange between parents, caregivers and physicians and provides an overview of the center’s clinical services and ongoing autism research at the School of Medicine.

In anticipation of the day-long symposium, we’ve asked Carl Feinstein, MD, director of the center, to respond to your questions about issues related to autism spectrum disorder and to highlight how research is transforming therapies for the condition.

At the Stanford Autism Center, Feinstein works with a multidisciplinary team to develop treatments and strategies for autism spectrum disorders. In providing care and support for individuals with autism and their families, Feinstein and colleagues identify ways of targeting the primary autism symptoms, while also paying attention to associated behavior problems that may hold a child back from school or community involvement or seriously disrupt family life.

Questions can be submitted to Feinstein by either sending a tweet that includes the hashtag #AskSUMed or posting your question in the comments section below. We’ll collect questions until Wednesday (May 15) at 5 PM Pacific Time.

When submitting questions, please abide by the following ground rules:

- Stay on topic

- Be respectful to the person answering your questions

- Be respectful to one another in submitting questions

- Do not monopolize the conversation or post the same question repeatedly

- Kindly ignore disrespectful or off topic comments

- Know that Twitter handles and/or names may be used in the responses

Feinstein will respond to a selection of the questions submitted, but not all of them, in a future entry on Scope.

Finally – and you may have already guessed this – an answer to any question submitted as part of this feature is meant to offer medical information, not medical advice. These answers are not a basis for any action or inaction, and they’re also not meant to replace the evaluation and determination of your doctor, who will address your specific medical needs and can make a diagnosis and give you the appropriate care.

Previously: New public brain-scan database opens autism research frontiers, New autism treatment shows promising results in pilot study, Autism’s effect on family income, Study shows gene mutation in brain cell channel may cause autism-like syndrome, New imaging analysis reveals distinct features of the autistic brain and Research on autism is moving in the right direction

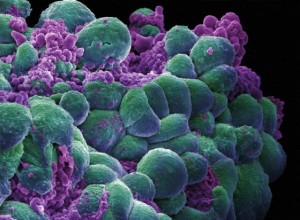

Photo by Wellcome Images