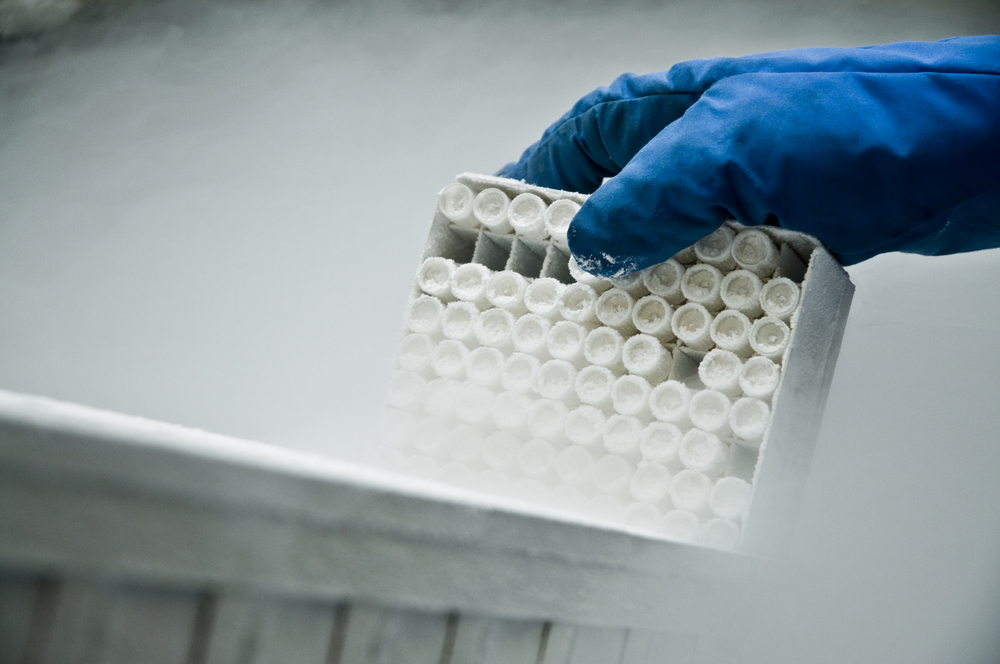

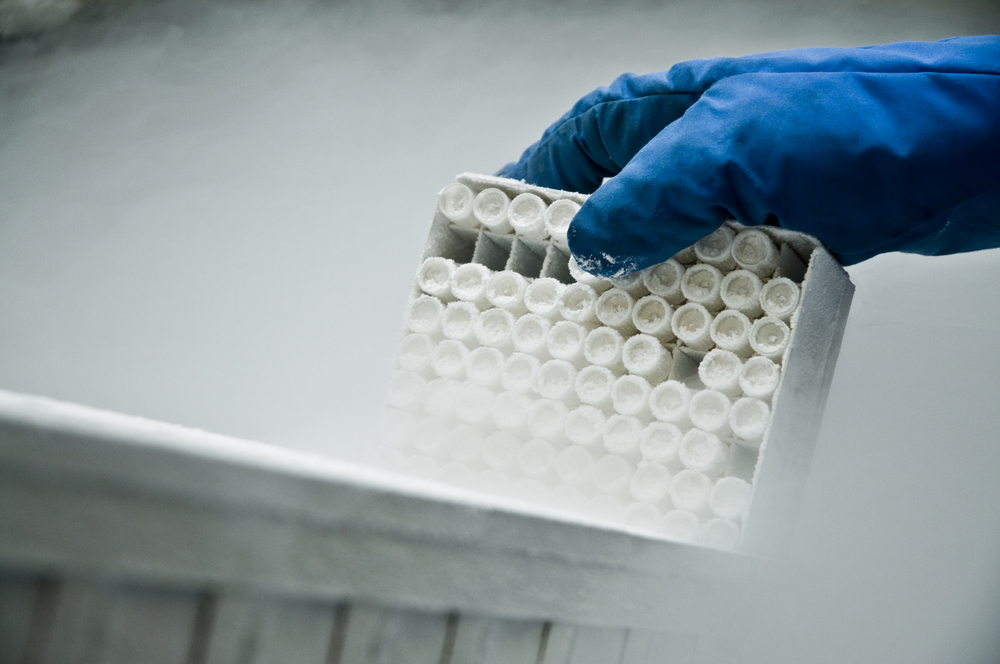

…Make that lots and lots of freezers.

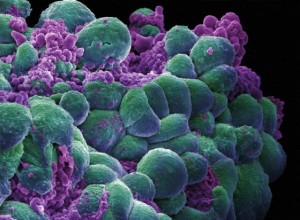

Freezers storing blood from thousands of generous research volunteers who donate samples when they are healthy - years or even decades before they might develop cancer, diabetes or other chronic diseases - can be found across the country. For scientists, these “pre-diagnostic” blood samples are likely to contain new biological clues of disease, perhaps molecular flags that cancerous cells are multiplying, or immunological rumblings as the immune system responds to the first signs of disease. Finding these signals is critical to future prevention, as they could represent the basis for blood tests or other means of ultra-early detection of disease.

The statistics involved in gathering enough pre-diagnostic blood samples to make them useful to research are daunting, though. For example, to study the blood of 100 women who go on to develop ovarian cancer in the next year, more than 200,000 samples from healthy women must first be stockpiled.

This month, Stanford’s partner, the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, along with their colleagues in Southern California at the City of Hope National Medical Center and UC Irvine, embark on an epic research effort: asking more than 50,000 female teachers, retired teachers and school administrators all over California - participants for the last 16 years in the long-term follow-up California Teachers Study - to provide a blood sample to be stored away for future research. This is no small logistical feat. First, teachers aged 50 to 79 from all over the state will be asked to participate and provide a convenient time and place for a phlebotomist to visit them for a blood draw. The samples will then be express shipped to a state-of-the-art biobank where they will be frozen in large banks of closely monitored freezers, alongside similar samples from other long-term studies.

The Teachers Study will continue its long-standing routines for tracking the health outcomes of each participant by continuously linking their names and other identifying information to California health databases, including death certificates, cancer registries and hospitalization discharge summaries. With time, the stored blood samples will turn into scientific gold, as we learn which of them were drawn from women who later developed cancer. In addition to looking for early proteomic markers of breast, ovarian and other cancers, the samples of women who ultimately developed cancer will undergo intense testing for chemical pollutant levels.

DNA will also be extracted from the blood, and from saliva samples donated by mail from teachers who live too far from the phlebotomists’ routes, or who volunteer to participate in that way. These DNA samples will likely be analyzed with others from very large prospective studies, like the ongoing study of more than 100,000 Northern California Kaiser Permanente members, whose saliva samples have been banked.

Some new clues to cancer can only be discovered when scientists study massive numbers of samples at the same time. To date, gene hunting has yielded a few blockbuster findings - most famously the rare BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes with very high risk for breast cancer - but no common genes or gene combinations amenable to broader risk profiling. This may be because past efforts didn’t have the statistical power to find the most likely culprits, subtle combinations of many gene mutations that together may provide some meaningful differentiator of risk. Very large datasets, containing not thousands but millions of genomes, will be required to establish reliable genomic markers of disease.

Genomic prediction for chronic disease and ultra-early blood tests for cancer aren’t here yet, but they’re getting closer. And when they do arrive, we can thank the volunteers with the foresight to file away their precious blood samples in many, many freezers.

Christina Clarke, PhD, MPH, is a research scientist at the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC) and a member of the Stanford Cancer Institute. Part of the Stanford Cancer Institute, the Cancer Prevention Institute of California conducts population-based research to prevent cancer and reduce its burden where it cannot yet be prevented.

Photo by Shutterstock

As a reminder, today is the final day of our Ask Stanford Med installment focused on breast cancer. Questions related to breast cancer screening, dense breast notification legislation and advances in diagnostics and therapies can be submitted to Stanford surgeon Fredrick Dirbas, MD, by either sending a tweet that includes the hashtag #AskSUMed or posting your question in the comments section of our previous entry. We’ll accept questions until 5 p.m. Pacific time.

As a reminder, today is the final day of our Ask Stanford Med installment focused on breast cancer. Questions related to breast cancer screening, dense breast notification legislation and advances in diagnostics and therapies can be submitted to Stanford surgeon Fredrick Dirbas, MD, by either sending a tweet that includes the hashtag #AskSUMed or posting your question in the comments section of our previous entry. We’ll accept questions until 5 p.m. Pacific time.