Apple- or pear-shaped: Which is better for cancer prevention?

on May 6th, 2013 No Comments

We always want what we don’t have. My teenage daughter is tall and beautiful (in my naturally biased and loving view). But she’s always complaining about her thighs. She thinks they’re too big and don’t look good in skinny jeans. What I see is a young girl with a fresh face, beautiful curves and a youthful spring of energy.

We always want what we don’t have. My teenage daughter is tall and beautiful (in my naturally biased and loving view). But she’s always complaining about her thighs. She thinks they’re too big and don’t look good in skinny jeans. What I see is a young girl with a fresh face, beautiful curves and a youthful spring of energy.

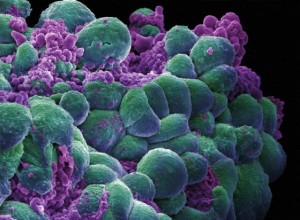

As a molecular epidemiologist, I see one more thing. She has a so-called “pear-shaped” body, which means she has larger thighs relative to a smaller waist, with most of her fat deposited in the lower body. In contrast, people who have “apple-shaped” bodies are heavier in the middle and have their body fat accumulated around the waist, closer to the heart, putting them at a higher risk for abdominal obesity. Many studies have shown that abdominal obesity has a more detrimental effect than overall obesity (as measured by body mass index, the metric calculated using height and weight) on a number of diseases, including type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain cancers (such as those of the breast, ovary, gallbladder and kidney). The specific biological mechanisms are not entirely clear, but we do know from recent research that fat (adipose tissue) is an endocrine organ that actively secretes a variety of chemicals, such leptin, adiponectin, estrogen and other hormones, and inflammatory cytokines. These markers have been linked to growth and proliferation of cancer cells.

The Stanford Cancer Institute and its affiliated research partner, the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC), currently are conducting studies to understand more clearly the molecular mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of abdominal obesity on cancers. A better understanding of how leptin and inflammatory markers associated with abdominal obesity can influence cancer risk at the molecular level will help clarify the specific steps involved in carcinogenesis, which in turn can aid the development of effective preventive strategies to stop or slow down cancer development.

Our genetic makeup determines largely which body type we are born with, pear or apple. But our eating habits, physical activity and weight management can also affect fat distribution and disease susceptibility. Regular exercise (three times a week) helps increase muscle mass, which in turn can enhance metabolism and lower the risk of metabolism-related conditions, including certain cancers. Whether cancer prevention and weight reduction guidelines differ for those with different body types is another important topic for future studies.

My daughter is the apple of my eye. But I’m glad that, unlike me, she’s a pear. She inherited her father’s body type. In theory, her risk of certain hormone-related cancers or metabolic disorders is lower than mine. So next time she complains about her thighs, I’ll share with her my recent work on abdominal obesity and cancer and try to convince her that she’s lucky to have “big” thighs.

Ann Hsing, PhD, MPH, is director of research for the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC). Part of the Stanford Cancer Institute, the CPIC conducts population-based research to prevent cancer and reduce its burden where it cannot yet be prevented.

Photo by KDL Designs