Distinction with a difference: Transgendered neurobiologist picked for National Academy of Science membership

on May 8th, 2013 No Comments

The National Academy of Sciences recently celebrated its 150th birthday by, among other things, conferring membership on Ben Barres, MD, PhD. Additional NAS admittees from Stanford were sleep scientist Emmanuel Mignot, MD, PhD, and bioengineer Steve Quake, PhD.

The National Academy of Sciences recently celebrated its 150th birthday by, among other things, conferring membership on Ben Barres, MD, PhD. Additional NAS admittees from Stanford were sleep scientist Emmanuel Mignot, MD, PhD, and bioengineer Steve Quake, PhD.

A distinguished scientist by anybody’s yardstick, as well as the chair of Stanford’s ironically named neurobiology department, Barres is a leading light in the study of glial cells (collectively known as glia), the 90 percent of all the cells in the brain that aren’t nerve cells.

The term”glia” is derived from the Greek word for glue. Like Rodney Dangerfield, glial cells once got no respect. They were thought of, in fact, as not much more than “brain glue”: mere structural scaffolds for the organ’s much more revered nerve cells.

Barres’ research has proved that hypothesis incorrect, to say the least. (For details, click here.) Discoveries coming out of his lab include, to name one example, glial cells’ crucial role in determining exactly when and where nerve-cell connections in the brain are made, tweaked to strengthen or weaken them, or destroyed.

You don’t get much more respectable than that: Those connections pretty much define the thoughts we have, the emotions and sensations we experience and the actions we take.

The man who, as much as anyone, has brought a set of unsung cells a newly elevated status would like to see another group get more respect: the estimated 0.3 percent of Americans who are transgender.

“I’m the first transgender scientist to make into the National Academy of Science,” says Barres, who began life under another first name: Barbara.

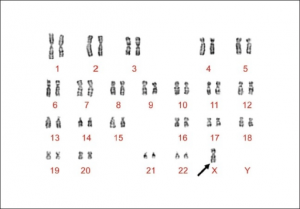

“We don’t know if other members past or present are or were transgender,” demurs an NAS representative. And after all, how would they? What kind of statistics could be compiled by an organization that doesn’t ask or track the sexual orientations, much less the gender identities, of its membership? Who would have even considered asking such a question 20 or 30 years ago, much less running sex-chromosome tests on cheek swabs from prospective, current or posthumous members?

But it’s a pretty safe bet that if any previously admitted NAS member were openly transgender, we’d have heard about it. (Transgendered computer scientist Lynn Conway was admitted to the National Academy of Engineering in 1989.)

One is tempted to compare Barres to Jackie Robinson, who broke the Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947 - except that the latter had to put up with a whole lot more grief from his fellow major-league ballplayers than Barres is likely to encounter from his peers.

“We heartily congratulate Prof. Barres on his election,” says NAS spokesperson Bill Skane.

In science, if anywhere, diverse perspectives drive innovation. ”Don’t ever let anyone make you feel bad about being different,” Barres tells young scientists. “Your difference is your greatest advantage.”

Previously: Malfunctioning glia - brains cells that aren’t nerve cells - may contribute big time to ALS and other neurological disorders, Neuroinflammation, microglia, and brain health in the balance and Unsung brain-cell population implicated in variety of autism