As I wrote about yesterday, new research in PLOS ONE suggests that sugar may play a stronger role in the origins of diabetes than anyone realized. Countries with more sugar in their food supplies have higher rates of diabetes, independent of sugar’s ties to obesity, other parts of the diet, and several economic and demographic factors, the researchers found.

As I wrote about yesterday, new research in PLOS ONE suggests that sugar may play a stronger role in the origins of diabetes than anyone realized. Countries with more sugar in their food supplies have higher rates of diabetes, independent of sugar’s ties to obesity, other parts of the diet, and several economic and demographic factors, the researchers found.

Although the study focused on diabetes rates among adults aged 20 to 79, it got me thinking about children’s health. Type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 90 percent of adult cases and is tied to obesity, used to be unheard-of in kids. But over the last few decades, it has been showing up in many more children and teens at younger and younger ages. Meanwhile, reducing kids’ sugar intake is already the focus of several preventive-health efforts, such as campaigns to remove sugary drinks from schools and children’s hospitals.

To get some perspective on how the new findings apply to children, I turned to Thomas Robinson, MD, a Stanford pediatric obesity researcher who directs the Center for Healthy Weight at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. Though Robinson, also a professor of pediatrics at the School of Medicine, cautioned that the epidemiological, “10,000-foot view” given by this study doesn’t prove a cause-and-effect link between sugar and diabetes in individuals - “it does not prove that the amount of sugar an individual eats is related to his or her diabetes risk,” he said - he had lots to say about the new results.

What do you think the findings mean for children’s health?

Children’s behaviors and environmental exposures have an impact on adult health and disease. This study used sugar data for entire countries, not individuals. That means that both the children and the adults were living in countries where higher levels of sugars in the food supply were associated with higher rates of diabetes. The potential implications are even stronger for children than adults. Children are being exposed to that environment for a much longer time. This is particularly a problem in developing countries where their food supplies, diets and weights are changing so rapidly.

A number of us here at Stanford focus on what we can do in early life, and throughout the lifespan, to prevent diseases that have origins in childhood but only first become apparent in adulthood. One can consider our work on obesity, physical activity, sedentary behavior and nutrition in children as really the prevention of diabetes, heart disease, many cancers and other chronic diseases in adults.

What factors has prior research identified as the biggest contributors to the increase in diagnoses of type 2 diabetes in pediatric patients?

The biggest contributor identified has been increased weight, but the increasing rate of type 2 diabetes at younger and younger ages probably reflects obesity plus lots of different changes, including changes in our diets, such as more sugars and processed foods, and less physical activity. The CDC now projects that 1 in 3 U.S. children will have diabetes in their lifetimes, and it will be 1 in 2 among African-American and Latina girls. That is a pretty scary thought. That is why we focus so strongly on helping families improve their diets, increase activity levels, and reduce sedentary time. We want to prevent and control excessive weight gain and all the problems that go with it, of which diabetes is just one.

In light of the new findings, do you think that parents whose children are not obese should be concerned about how sugar consumption could raise their children’s diabetes risk?

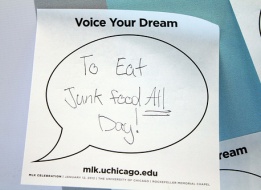

This study doesn’t really address the question of what happens at the level of an individual child. However, it is still consistent with the advice we would give now, for both normal weight and overweight children. I definitely recommend that parents try to reduce sugars in their children’s diets. Most parents are not even aware how much sugar their children are eating. Sure, sodas and sweets are the obvious sources but sugars are also added to seemingly all processed foods, including even bread, pizza and French fries. The added sugars are just empty calories — providing extra calories and no additional nutritional benefit. So I recommend that all parents try at least to reduce the obvious sources of sugary drinks, sweets and desserts.

Continue Reading »