Ask Stanford Med, Behavioral Science, Mental Health, Stanford News

Marissa Fessenden

on June 27th, 2012

Stress is an inevitable part of daily life and sometimes it can feel as though you might crack under the pressure. While you may never be able to eliminate stress completely, you can learn to identify its source and manage it better. This month, Stanford health psychologist Kelly McGonigal, PhD, explores the evolutionary roots of stress and how our stress instincts interact with modern challenges in her Stanford Continuing Studies course.

In the following Q&A, McGonigal discusses the science of stress and how it affects the mind-body relationship, and she offers tips on managing the body’s flight or fight response.

How does stress affect the human body?

The physical stress response is more complex than most people realize. Sure, we recognize this when we’re under pressure. The heart speeds up, our blood pressure spikes and maybe we feel our stomachs churn and our jaws clench. But these stress symptoms are just a small part of a complicated cascade of changes in your brain and body.

It begins when the brain detects - or even just imagines - any kind of threat. It could be to your survival, like realizing a car is about to crash into you. Or it could be a threat to your ego, like getting criticized by your boss. The brain then unleashes a stream of chemicals that shifts the mind and body into emergency mode.

The brain shuts down regions important for long-term planning and juices up regions that help you react quickly and without much thinking. The body sends its resources to the systems that will help you flee from danger or fight to defend yourself (that’s why the heart is pounding!). It takes those resources away from things like digestion, reproduction and healing. That’s a big part of why chronic stress is so harmful for health and can increase risk of heart disease, infections and digestive or metabolic disorders.

At the same time all this is happening, stress hormones released throughout the body are shaping our behavior. The hormone oxytocin is a key part of the stress response for women. It creates the desire to be close to others, to seek social support and hugs and protection. Among men, there may be an increase in vasopressin and testosterone. These two hormones increase the competitive drive and desire to defend yourself and those you care about. And among just about everyone, the stress hormone cortisol makes us crave whatever we are addicted to, from cigarettes to cookies to checking our phones or email.

Continue Reading »

Image of the Week

Marissa Fessenden

on June 10th, 2012

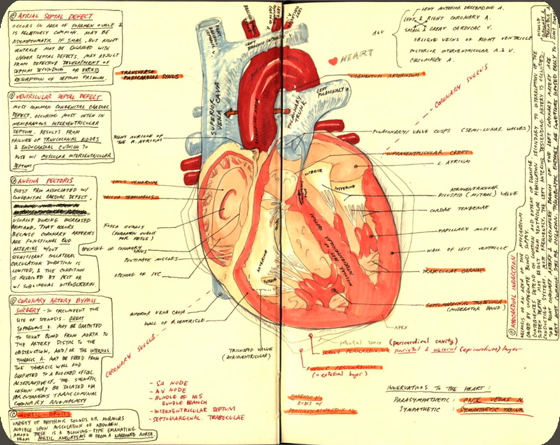

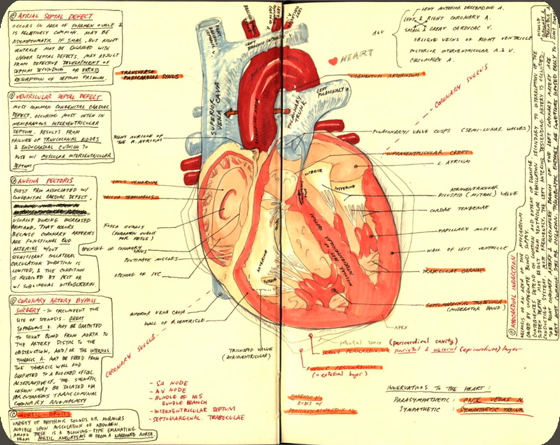

Here a human heart takes shape in the pages of medical illustrator Sayaka Isowa’s sketchbook. She writes:

“Since childhood I had a passion for drawing and was inspired by the beauty of the human body and living species. I discovered biomedical art through my illustration classes and became fascinated by the collaboration of art and science.”

There are more fascinating works in progress and sketches on Isowa’s blog.

Photo courtesy Sayaka Isowa

History, In the News

Marissa Fessenden

on June 8th, 2012

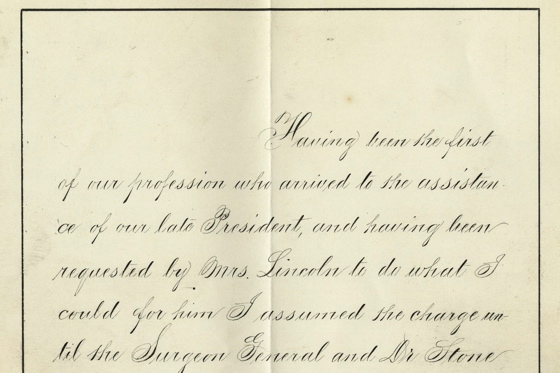

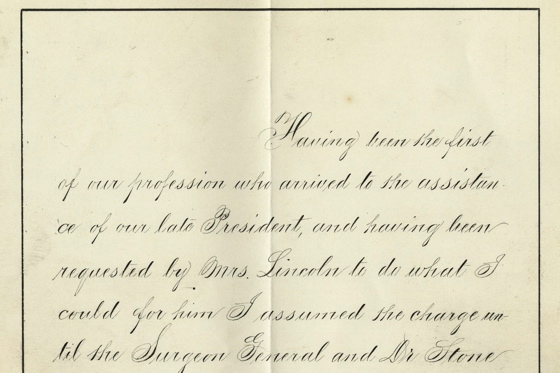

As has been covered widely in the news, a researcher hunting through the National Archives for letters by Abraham Lincoln recently uncovered a doctor’s report of the 16th president’s assassination.

As has been covered widely in the news, a researcher hunting through the National Archives for letters by Abraham Lincoln recently uncovered a doctor’s report of the 16th president’s assassination.

Army surgeon Charles Leale, MD, attended the theater the night the President was killed and was the first doctor on the scene. The report reads:

“Having been the first of our profession who arrived to the assistance of our late President, and having been requested by Mrs. Lincoln to do what I could for him I assumed the charge until the Surgeon General and Dr Stone his family physician arrived, which was about 20 minutes after we had placed him in bed in the house of Mr. Peterson opposite the theatre, and as I remained with him until his death, I humbly submit the following brief account.”

A news article from CNN captures the reaction of the researcher, Helena Iles Papaioannou, who works for Papers of Abraham Lincoln:

“You get a sense of helplessness,” said Papaioannou. “I think it was fairly immediate that he realized that the president wasn’t going to recover.” Papaioannou said that, to her, the most moving part of Leale’s report is his account of covering Lincoln shortly after the president was carried to a back bedroom of the Peterson House.

“He talks about how the president’s legs — his lower extremities, from the knees down — were cold, and they brought him hot water bottles and hot blankets. I find that a very touching part of the report.”

The report largely confirms other accounts of the assassination, but adds a few details about times and pulse rate during the night.

via 80beats

Image by the Papers of Abraham Lincoln

Neuroscience, Stanford News

Marissa Fessenden

on June 6th, 2012

Reaching out to touch an object is a simple task, but how our brain coordinates that movement has proved tricky for scientists to decipher. Scientists investigating this puzzle have traditionally based their theories on the way the brain’s visual cortex deals with color, intensity and form. But now researchers propose a new theory for physical movement, one based on rhythmic patterns.

Reaching out to touch an object is a simple task, but how our brain coordinates that movement has proved tricky for scientists to decipher. Scientists investigating this puzzle have traditionally based their theories on the way the brain’s visual cortex deals with color, intensity and form. But now researchers propose a new theory for physical movement, one based on rhythmic patterns.

A team of electrical engineers and neuroscientists based at Stanford linked coordinated patterns of activity in groups of neurons to movements in shoulder muscles.

The team, led by electrical engineer Krishna Shenoy, PhD, studied brain activity in monkeys reaching to touch a target. The patterns they observed could be explained by summing two simple rhythms, they report (subscription required) in a recent issue of Nature. The neurons did not fire in isolation, but in a kind of concert. A story published today in the Stanford Report explains:

“Under this new way of looking at things, the inscrutable becomes predictable,” said [first author Mark Churchland, PhD, now a professor at Columbia]. “Each neuron behaves like a player in a band. When the rhythms of all the players are summed over the whole band, a cascade of fluid and accurate motion results.”

—

The team studied non-rhythmic reaching movements, which made the presence of rhythmic neural activity a surprise even though, the team notes, rhythmic neural activity has a long precedence in nature. Such rhythms are present in the swimming motion of leeches and the gait of a walking monkey, for instance.

“The brain has had an evolutionary goal to drive movements that help us survive. The primary motor cortex is key to these functions. The patterns of activity it displays presumably derive from evolutionarily older rhythmic motions such as swimming and walking. Rhythm is a basic building block of movement,” explained Churchland.

Photo by pawpaw67

Microbiology, Stanford News

Marissa Fessenden

on June 6th, 2012

In a sense, our body is not our own. Microbes living in and around us outnumber our own human cells ten to one. A review in a special issue of Science leverages ecological theory to explore these most intimate relationships.

The authors, led by Stanford’s David Relman, MD, examine scientists’ understanding of how our microbial communities vary over time. They compare a newborn to communities moving into a newly created habitat (in ecology the common example is a new island), a human after antibiotic treatment to a disturbed habitat (a forest after a fire) and a person infected by a pathogen to a habitat under invasion from a foreign species.

This is not the first time experts have argued the microbes in our body follow patterns observed in larger ecosystems. That thinking has also led to a call for epidemiologists to learn ecology as a way to consider the microorganisms that live inside us.

The paper concludes with a challenge to the traditional perspective of the human body as “a battleground on which physicians attack pathogens with increasing force, occasionally having to resort to a scorched-earth approach to rid a body of disease.” Instead, the authors suggest clinicians could cultivate the human microbiome like park managers, encouraging conditions that favor good microbes instead of bad. By measuring biomarkers constantly, doctors could track the progress of disease and treatment. “Such an information-intensive approach, guided by ecological theory, has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of disease,” they write.

Previously: Contemplating how our human microbiome influences personal health and New York Times explores our amazing microbes

Photo by Eek

Stanford News, Transplants

Marissa Fessenden

on June 5th, 2012

The story of Anabel Stenzel and Isabel Stenzel Byrnes, twins born with cystic fibrosis, is now getting the silver screen (or liquid crystal, if you prefer) treatment. A film based on their memoir releases digitally in the U.S. today.

The half-Japanese sisters graduated from Stanford in 1994 and now work at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. As advocates for organ donation, they travel and tell the story of how lung transplants changed their lives. The film revolves around the twins’ speaking tour in Japan, where attitudes toward organ donation are vastly different from here in the U.S.

Producer Andrew Byrnes knew of the story because he was closely connected to Isa: The two met at Stanford and are married. “When we first met I knew nothing about cystic fibrosis and transplant,” Byrnes says. “But the twins - who they are and what they have done - has been an inspiration. Sharing that with the world is something that is important to me.”

Byrnes originally approached filmmaker Marc Smolowitz to ask if the Academy-award nominated director knew anyone who might record the twins’ speeches in Japan. Smolowitz read the book and was captivated. “I read fell in love with Ana and Isa as writers and characters,” he says.

In the following Q&A, Smolowitz and Byrnes discuss the message and making of the film.

What was it like working with the sisters?

Smolowitz: It was an a amazing collaboration. They are both writers and storytellers and I am a storyteller. We worked very closely together and I brought them into the process. We mapped their itinerary-where do they go throughout the year as they do their work as organ donation advocates. When you focus so closely on two people such as Ana and Isa you are really building on their credibility. Ana and Isa are well-loved by the people that know them and the work they do.

Did anything surprising or unexpected come out of the collaboration?

Smolowitz: I guess the most surprising moment in production was right at the start of editing. I had just hired the editors and we spent the weekend giving them a chance to know Ana and Isa. We visited both of their houses. I had always known that the twins were very active with scrapbooks, photo albums and journals, but I hadn’t realized the extent of it. They have hundreds of volumes of diaries, journals, scrapbooks and photo albums that they’ve made-just physical evidence that they have lived. It’s like a lightbulb went off for me. These girls had to keep these journals because they had to record their lives. They had to show that they had lived. When you see the movie you realize it is all kind of wrapped around this photographic world.

Continue Reading »

Image of the Week

Marissa Fessenden

on June 4th, 2012

These multicolored tentacles are actually blood vessels emerging from an eye’s blind spot. Also called the optic disc, this is the spot where the optic nerve attaches to the retina. The confocal micrograph shows the optic disc in black, cells lining the blood vessels in red and vessel contents in green. Retinal cells are stained blue.

Photo by Freya Mowat / Wellcome Images

Global Health, HIV/AIDS, LGBT

Marissa Fessenden

on May 30th, 2012

So far, the spread of HIV in China has remained at levels less than one-fifth that of Europe and the United States, but now researchers warn that discomfort over discussing sex is a major problem. According to the Chinese Ministry of Public Health, the transmission of HIV between homosexuals has risen (.pdf) from 0.3 percent before 2005 to 13.7 percent in 2011.

In a comment published online today in Nature a consortium of Chinese researchers compare attitudes toward sexuality in China today to those in Western countries a quarter of a century ago. They write:

Chinese people aren’t uncomfortable just in discussing homosexuality — sex in general is still considered extremely personal and is rarely addressed openly or directly, irrespective of orientation. This discomfort has resulted in a pervasive stigma against people with HIV, a lack of general sex education for young people and poor epidemiological data about the spread of HIV in some populations around the country.

The result is a hidden population of individuals who are afraid to seek out HIV information resources or testing and counselling centres. Poorly educated, unaware of their HIV status and under pressure to conceal their sexual encounters, these men often engage in high-risk behaviour. And once one man hiding his activity becomes infected, the disease will spread among his partners, in an ongoing cycle. It is therefore no surprise that incidence of HIV has skyrocketed in this population.

Although cases of HIV among homosexual men represent a much smaller portion of those infected, (just 13.7 percent compared to 50 percent in the U.S.) the researchers say there is cause for concern. They call for more testing and public programs as well as better social and media awareness:

Leading by example is one of the most powerful ways to combat stigma … In 2003, a man stood up during an AIDS summit with former US President Bill Clinton at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and in doing so became one of the first Chinese people to publicly reveal his HIV status. Clinton embraced the man, named Peng-fei Song, bringing him positive media attention. Song later became a strong advocate for HIV awareness and prevention. China needs to encourage more individuals affected by HIV/AIDS to step up and help to change people’s perception of the disease.

Image of the Week

Marissa Fessenden

on May 27th, 2012

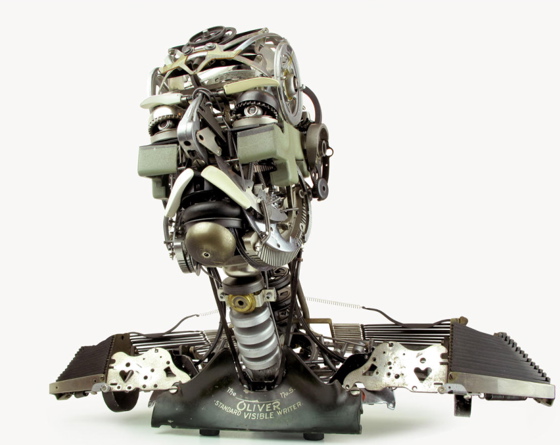

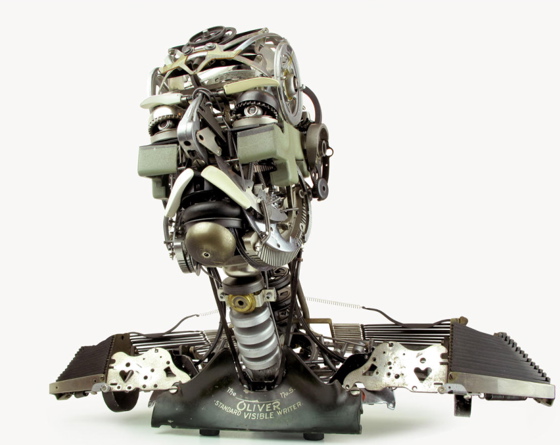

This gorgeously detailed human head and shoulders was created by Oakland-based artist Jeremy Mayer. He writes:

I disassemble typewriters and then reassemble them into full-scale, anatomically correct human figures. I do not solder, weld, or glue these assemblages together- the process is entirely cold assembly. I do not introduce any part to the assemblage that did not come from a typewriter.

Find more sculptures and photos of Mayer’s process on his tumblr.

Via Street Anatomy

Health Disparities, Research, Stanford News

Marissa Fessenden

on May 23rd, 2012

Major gaps in our understanding of health disparities and their causes still exist, and one population often overlooked is Asian Americans. Now, a 5-year, $2 million grant will allow local researchers to investigate disparities in health and mortality among Asians in the U.S. Stanford’s Mark Cullen, MD, and Latha Palaniappan, MD, of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation are leading the study.

The team will comb through census and CDC data to compare major Asian sub-populations and look for health differences between recent immigrants, their children and subsequent generations. Cullen said they hope to uncover social and environmental factors that influence health disparities, and he recently spoke with me more in-depth about the work:

What kind of patterns might you find in the study of Asian Americans?

We have some reason to believe that, for example, the Japanese population has a uniquely low risk for heart disease, a somewhat higher risk for stroke, and a higher risk for cancer. Likewise the rates of cancer are somewhat high among Chinese and Vietnamese people. Conversely, we expect extremely high rates of cardiovascular disease in South Asia because this population’s rate of diabetes seems to be quite high. But these are just suspicions based on incomplete data we have.

It’s evident that some of what we think about the various populations is somewhat stereotypical and not necessarily completely right. One of the things we’re going to be trying to do is look at the complete picture. In one part of our study, we’ll be doing more analysis to understand patterns.

What are some of the difficulties involved in separating out the underlying racial or ethnic and socioeconomic factors involved in health disparities?

The number of counties where Asians reside in large numbers is still small, and the data have been available for them for only a few years, hence there are data limitations. In our last study [which examined premature mortality among whites and African Americans] we were dealing with tens and maybe hundreds of millions. Now, we are dealing with hundreds of thousands or one million - much smaller populations. And these populations also tend to live in relatively limited areas. Although places like the Bay Area, Southern California, New York and a few other large metropolitan areas are rich in these populations, many parts of the country are not. So, some questions are going to be harder to answer.

A second problem is that Asians have immigrated to the U.S. in waves so that, for example, the South Asian Americans are mostly fairly recent and there may not yet be a large enough experience to estimate premature mortality, or to compare first and later generations yet.

Continue Reading »