Peering into the brain to predict kids’ responses to math tutoring

on April 29th, 2013 No Comments

Third grade is a critical year for learning arithmetic facts, but while math comes easily to some children, others struggle to master the basics.

Third grade is a critical year for learning arithmetic facts, but while math comes easily to some children, others struggle to master the basics.

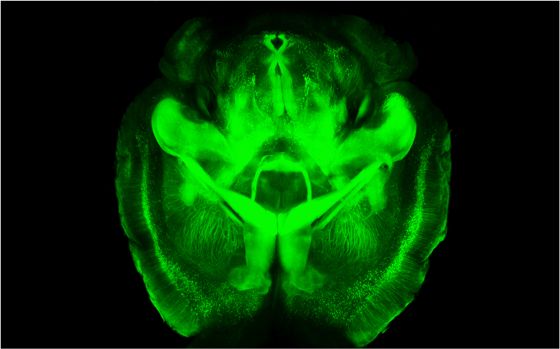

Now, researchers at Stanford have new insight into what separates adept young math students from those who have difficulty. The difference, described in a paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can’t be detected with traditional intelligence measures such as IQ tests. But it shows up clearly on brain scans, as the new study’s senior author explained in our press release:

“What was really surprising was that intrinsic brain measures can predict change — we can actually predict how much a child is going to learn during eight weeks of math tutoring based on measures of brain structure and connectivity,” said Vinod Menon, PhD, the study’s senior author and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

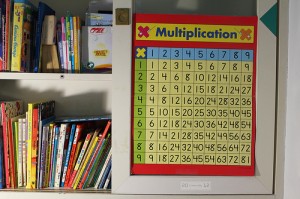

Menon’s research team conducted structural and functional MRI brain scans before third-grade students received 8 weeks of individualized math tutoring. The tutoring followed a well-validated format, combining instruction on math concepts with practice of math problems emphasizing speed. All the children who received math tutoring improved their math performance, but the performance improvements varied a lot — from 8 percent to 198 percent.

A few specific brain characteristics were particularly good at predicting which kids would benefit most from tutoring. In particular, a larger and better-wired hippocampus predicted performance improvements. The brain structures highlighted in the study are implicated in forming memories, and differ from the portions of the brain that adults use when they are learning about math. The fact that these systems are involved helps to explain why the combination of conceptual explanations and sped-up practice that the study’s tutors used is effective, Menon explained:

“Memory resources provided by the hippocampal system create a scaffold for learning math in the developing brain,” Menon said. “Our findings suggest that, while conceptual knowledge about numbers is necessary for math learning, repeated, speeded practice and testing of simple number combinations is also needed to encode facts and encourage children’s reliance on retrieval — the most efficient strategy for answering simple arithmetic problems.” Once kids are able to pull up answers to basic arithmetic problems automatically from memory, their brains can tackle more complex problems.

Next, the researchers plan to examine how brain wiring changes over the course of tutoring. The new findings could also help educators understand the basis for math learning disabilities, and may even provide a foundation for figuring out what kind of instruction could help children overcome these problems.

Previously: New research tracks “math anxiety” in the brain and We’ve got your number: Exact spot in brain where numeral recognition takes place revealed

Photo by Canadian Pacific