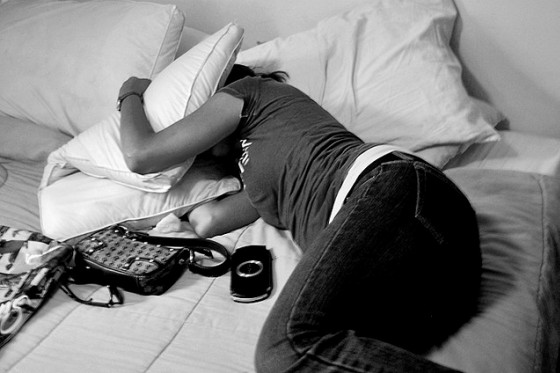

Prolonged fatigue and mood disorders among teens

on May 1st, 2013 No Comments

Past research suggests that poor sleep during adolescence can have “lasting consequences” on the brain. Now a new study offers additional insights into the negative health effects of sleep deprivation on teens’ health.

Past research suggests that poor sleep during adolescence can have “lasting consequences” on the brain. Now a new study offers additional insights into the negative health effects of sleep deprivation on teens’ health.

In the study, researchers analyzed data collected from more than 10,000 adolescents as part of the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement. As MedPage Today reports, their findings show that prolonged fatigue is associated with mood and anxiety disorders among teens:

In a nationally representative sample of adolescents ages 13 to 18, 3% reported having extreme fatigue lasting at least 3 months and about half of those who did also had mood or anxiety disorders, according to Kathleen Merikangas, PhD, of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues.

Having both prolonged fatigue and a mood or anxiety disorder was associated with poorer physical and mental health and greater use of healthcare services compared with having only one of the disorders, the researchers reported online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

“This suggests that the presence of fatigue may be used in clinical practice as an indicator of a more severe depressive or anxiety disorder,” Merikangas and colleagues wrote.

Stanford physician Michelle Primeau, MD, recently explored the topic of how teen sleep habits affect mood in a recent Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine blog entry on the Huffington Post. In her post, she explains why teens in particular are at risk of chronic partial sleep deprivation:

Teenagers need to sleep about nine hours, and as they get older, they tend to sleep less. This is not because they need less, but because they are busier with school, jobs, extracurricular activities, and friends. Their biology also will often shift so that they tend to fall asleep later and want to sleep in later, an occurrence that may represent delayed sleep phase syndrome. This may explains why your teenager is so hard to wake up on Saturdays. But this shift to a later bedtime, both of social and biologic causes, in combination with fixed early school times, means that many teenagers are walking around sleep deprived.

Previously: Can sleep help prevent sports injuries in teens?, Study shows link between lack of sleep and obesity in teen boys, Study shows lack of sleep during adolescence may have “lasting consequences” on the brain, Teens and sleep: A Q&A, Sleep deprivation may increase young adults’ risk of mental distress, obesity, Districts pushing back bells for the sake of teens’ sleep and Lack of sleep may be harmful to a teen’s well-being

Photo by lunchtimemama