Really. Come on. Who isn’t interested in hair? Hair growth, hair loss, hair thickness, hair shape, hair location. I’d bet that everyone of us spends at least a minute or two each day thinking about (or, if you’re like me, futilely plucking and prodding at) the state of our locks.

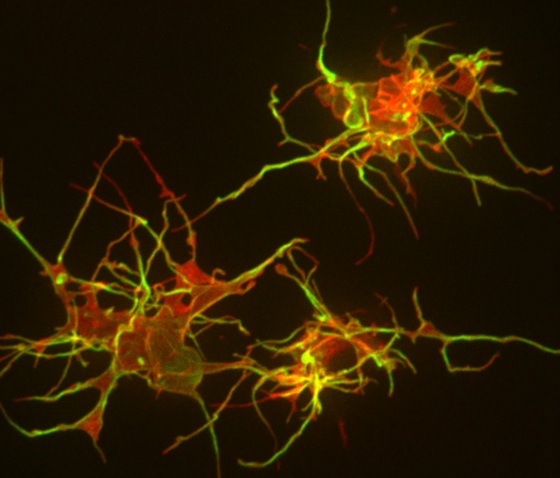

Now Stanford researchers have delved deep into the cells surrounding our hair follicles to better understand what makes them grow and maintain hair. Perhaps not surprisingly, the answer lies in the stem cells (here, called ‘bulge cells’) within the follicle.

Specifically, research associate Yiqin Xiong, PhD, and associate professor of medicine Ching-Pin Chang, MD, PhD, have identified a signaling circuit that controls the cells’ activity. The research was published yesterday in Developmental Cell (subscription required). As Chang explained in an e-mail to me:

By promoting self-renewal of stem cells, this circuit maintains a healthy pool of bulge cells for repeated cycles of hair growth and regeneration. Each cycle of hair regeneration is initiated by the activation of this circuit in those bulge cells, and subsequent growth of the hair is sustained by the circuit in hair matrix cells. Besides hair regeneration, the circuit is triggered by skin injury to stimulate migration of the bulge cells to the wounded area to differentiate into epidermal cells, thereby regenerating epidermis over the wounded skin.

In the past, news about hair growth (and how to stimulate it) has been a trigger for a deluge of interest from media and individuals struggling with… (how shall we say it?) ‘hair problems.’ But the research has many implications beyond hair, or the lack thereof. For example, the presence or absence of hair follicles on the skin affect how the skin heals after a wound, and whether a scar remains. According to Chang:

This molecular circuit in the hair follicle can be targeted for therapeutic purposes. Because of its activity in hair regeneration, inhibition of this circuit can reduce hair growth in patients with excessive hairiness (hirsutism), whereas activation of this pathway can promote hair growth for people with baldness (alopecia). Also, for its activity during epidermal regeneration, activation of the circuit can facilitate wound healing for patients receiving surgery and for diabetic patients who have wounds that are difficult to treat. The activity of the circuit in both hair follicle and epidermal regeneration may have additional therapeutic benefit. Lack of hair follicles in a wounded area is a hallmark of scar formation. Targeting this pathway has the advantage of promoting both hair follicle formation and wound repair, thus reducing scar formation in the wound.

Interestingly, one of the key molecules, called Brg1, involved in this regulatory circuit has also been implicated in previous work from Chang’s lab in the enlargement of the heart and in fetal heart development. It’s apparent this story has many layers, some more than skin deep.

Previously: Examining the role of genetics in hair loss and Epigenetics: the hoops genes jump through,

Photo by Furryscaly

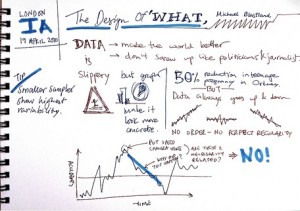

Here’s a developing social media story of interest to scientists, clinicians and the general public. National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, kicked a hornets’ nest on Twitter earlier today with a tweet asking researchers to describe the direct impact of the U.S. budget sequestration, which began in March, on their research and lives. He asked respondents to use the hashtag #NIHSequesterImpact. The responses (some of which I’ve included below) are fascinating and depressing:

Here’s a developing social media story of interest to scientists, clinicians and the general public. National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, kicked a hornets’ nest on Twitter earlier today with a tweet asking researchers to describe the direct impact of the U.S. budget sequestration, which began in March, on their research and lives. He asked respondents to use the hashtag #NIHSequesterImpact. The responses (some of which I’ve included below) are fascinating and depressing: