As the editor of Stanford Medicine, I think a lot about new research, new discoveries, new treatments. So it’s no wonder I find stories of long ago a refreshing change when I’m reading for pleasure. A look at my 10 favorites this year shows my predilection, though there’s lots of new here too. History fan or not, if you read just one, read about the immortal jellyfish! I can’t stop thinking about them.

Undead: The rabies virus remains a medical mystery, by Monica Murphy and Bill Wasik, Wired

An account of a modern attempt to cure rabies, with lots of history woven in.

Can a jellyfish unlock the secret of immortality? by Nathaniel Rich, New York Times Magazine

Including wondrous jellyfish that grow younger and a researcher who breaks the mold, and it’s told with humor and lyricism.

Two hundred years of surgery, by Atul Gawande, New England Journal of Medicine

For gems like this: “Liston operated so fast that he once accidentally amputated an assistant’s fingers along with a patient’s leg, according to Hollingham. The patient and the assistant both died of sepsis, and a spectator reportedly died of shock, resulting in the only known procedure with a 300% mortality.”

Post-Prozac nation: The science and history of treating depression, by Siddhartha Mukherjee, New York Times

Everything we knew about antidepressants like Prozac was wrong. But that’s OK.

The nature of the Knight Bus, by Chris Gunter, Story Collider

A look behind the scenes at top science journal Nature from one of the journal’s editors.

The island where people forget to die, by Dan Buettner, New York Times Magazine

On mellowing out on a Greek island to live to 100. It got me thinking about how to bring more mellowness into my life.

Fear fans flames for chemical makers, by Patricia Callahan and Sam Roe, Chicago Tribune

A great investigation into a chemical industry-funded front group’s deceptive campaign that fueled demand for flame retardants in furniture, electronics and baby products among many other items. The whole four-part series is worth reading. It also explains that the chemicals have been linked to cancer, neurological deficits, developmental problems and impaired fertility — and not only that, but they don’t work.

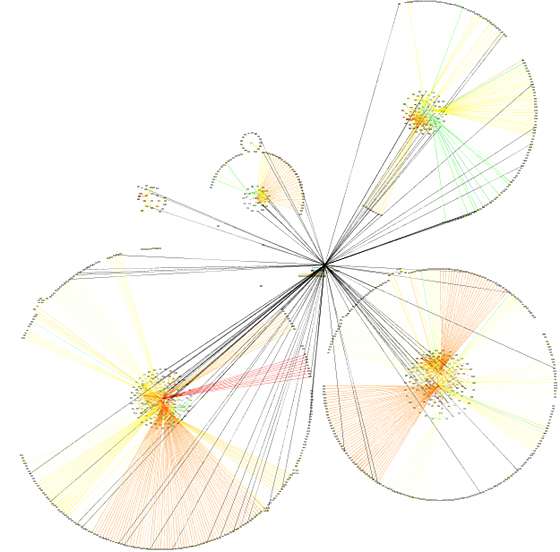

The measured man, by Mark Bowden, The Atlantic

On one man’s effort to use big data as a tool to guide him to better health. This is either insane, the future, or both.

A family learns the true meaning of the vow ‘in sickness and in health’, Washington Post Magazine

A heartrending, inspiring read for me, though not for all - as evident by the comments.

Previously: My top medical reads of 2011 (aside from those I edited)

From Dec. 24 to Jan. 7, Scope will be on a limited holiday publishing schedule. During that time, it may also take longer than usual for comments to be approved.

I felt a little guilty about pushing my colleague John Sanford to confront his blood phobia as part of a story he was writing for Stanford Medicine magazine. I feel fine about it now, though. While writing it, John overcame the phobia! And the story turned out very well too. In fact, it was recently singled out by long-form journalism curator Longreads as a story worth reading.

I felt a little guilty about pushing my colleague John Sanford to confront his blood phobia as part of a story he was writing for Stanford Medicine magazine. I feel fine about it now, though. While writing it, John overcame the phobia! And the story turned out very well too. In fact, it was recently singled out by long-form journalism curator Longreads as a story worth reading.