Image of the Week, Imaging, Microbiology, Stanford News

Lisandra West

on December 19th, 2010

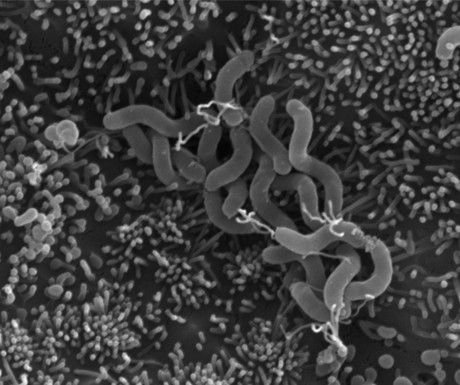

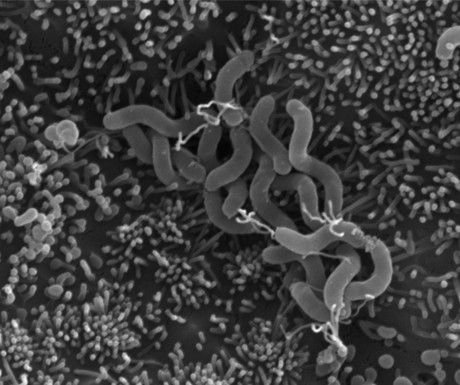

There’s a 50 percent chance that your stomach is home to the spiral-shaped Helicobacter Pylori, a bacterium that chronically infects the human stomach and occasionally gives rise to ulcers. It’s estimated that half of the world’s population is infected - but 80 percent of infected individuals are asymptomatic.

This week’s image, taken with a scanning electron microscope, shows H. Pylori colonizing the ciliated epithelial cells that line the inside of the stomach. Manuel Amieva, MD, PhD, uses live cell imaging and cell culture to study the pathogen. His research group asks some interesting questions about how the microbes make the highly acidic, inhospitable stomach environment their home. According to their paper published in PLoS Pathogens:

We discovered that [H. Pylori] is able to grow on the surface of epithelial cells, even in conditions where the free-swimming bacteria are rapidly killed. One mechanism involved in this ability to colonize the cell surface is the virulence factor CagA, which is injected directly into host cells by the bacteria. We found that CagA’s ability to perturb cell polarity is important for the efficient survival and growth of Hp on the apical surface of the host cell.

Research has shown that CagA and other virulence factors used by H. pylori to manipulate host cells may also trigger changes that may ultimately lead to gastric cancer. Scientists are investigating whether the link between H. pylori and stomach cancer merits treatment for infected individuals.

Previously: Researchers manipulate microbes in the gut, Bacterial balance in gut tied to colon cancer risk and Guts and glory: Growing intestinal tissue in a lab dish

Photo by Shuman Tan and Lydia-Marie Joubert

From December 20 to January 3, Scope will be on a limited holiday publishing schedule. During that time, you may also notice a delay in comment moderation. We will return to our regular schedule on January 3.

In the News, Neuroscience

Lisandra West

on December 16th, 2010

The amygdala is a region of the brain involved in creating the fear response. So here’s a question that falls into the realm of weird science: If the amygdala gets damaged, might a person be incapable of experiencing fear? Oddly, the answer may be yes.

Wired Science is reporting on a fascinating study (subscription required) about a woman who apparently knows no fear:

[The woman] has an unusual genetic disorder called Urbach-Wiethe disease. In late childhood, this disease destroyed both sides of her amygdala, which is composed of two structures the shape and size of almonds, one on each side of the brain. Because of this brain damage, the woman knows no fear, the researchers found.

According to the story, researchers were unable to frighten the woman. She experienced no fear of scary movies, snakes, spiders or even public speaking.

Behavioral Science

Lisandra West

on December 16th, 2010

Everyone loves the holidays, but, as the season marches on, many people (myself included) find themselves wishing they were a bit better at restraining themselves around holiday treats. If you’re open to creative suggestions, you might appreciate the results of a recent study in Science.

In that study, researchers asked study participants to imagine eating M&Ms before offering them different quantities of the candy. And Nobel Intent reports:

It turns out that the more M&Ms a participant imagined eating, the fewer they actually ate when the candies were in front of them. People that imagined eating 30 candies ate half as many M&Ms as those who imagined eating just three did.

Photo by Dyanna

Image of the Week

Lisandra West

on December 12th, 2010

This photo was taken sometime between 1859 and 1936 at the Stanford School of Nursing in Lane hospital. The identities of other women in the group are unknown, making this picture another “mystery” item in the Stanford Medical History Center’s collection.

We invite any reader who might recognize any individual depicted here to leave a note in the Comments section.

This image is No. 6 of 6 in our series featuring women throughout medical history. The images are from the Medical History Center’s Flickr photo stream.

Previously: Working with heart transplant doctor Norman Shumway, Early Contributions to Stanford Hospital, Gladys Louise Goselin with an unidentified baby, Mystery photo from Stanford Medical History Center, and Doctors and nurses in the operating room at Lane Hospital

Health and Fitness, Media

Lisandra West

on December 10th, 2010

I tried to make running a few times a week part of my personal exercise program for years. I found that adherence to this goal significantly improved when I convinced a friend to join me for the early morning jaunts.

Interestingly, researchers providing Internet-based health programs are finding that this peer motivation technique works well online too. According to an article in Healthcare IT News:

Caroline Richardson, MD, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School, and her colleagues found that adding an interactive online community to an Internet-based walking program significantly decreased the number of participants who dropped out.

Program results showed that 79 percent of participants who used online forums to motivate each other stuck with the 16-week program. Only 66 percent of those who used a version of the site without the social components completed the program.

More details on how social media can boost participation in health programs are available in the full article.

Photo by ArdonLXXXIII

NIH, Stanford News

Lisandra West

on December 10th, 2010

The difficulty of obtaining funding to support one’s research is an issue faced by academic scientists at every level. Coming from a research background myself, I am familiar with the struggle and was pleased to hear that Stanford’s Faculty Senate recently approved a new funding opportunity for clinical fellows and MD postdocs. According to an article in the Stanford Report:

Under the trial plan, up to 10 postdoctoral MD fellows a year will be able to submit grant applications - one time only - as principal investigators on projects.

Harry Greenberg, MD, senior associate dean for research at the School of Medicine, explained the experimental nature of the plan in a quote:

What you have before you is a very limited proposal to evaluate whether we can provide certain exceptional postdoctoral MD fellows with the opportunity to get an R01 grant [Research Project Grant from the National Institutes of Health] that will help them in getting their first faculty position.

Photo by tigerweet

Image of the Week

Lisandra West

on December 5th, 2010

Here Norman Shumway, MD, PhD, is shown with two unidentified hospital employees. This is another “mystery” photo in the collection of the Stanford Medical History Center. If any readers know the identities of the two women depicted, please leave them in the comments.

This image is No. 5 of 6 in a series of images featuring women throughout medical history. The images are from the Medical History Center’s Flickr photo stream.

Previously: Gladys Louise Goselin with an unidentified baby, Mystery photo from Stanford Medical History Center, Doctors and nurses in the operating room at Lane Hospital, and Early contributions to Stanford Hospital

Image of the Week

Lisandra West

on November 28th, 2010

This photo shows women at work in a laboratory in Stanford’s Palo Alto Hospital in 1931, the year construction of the on campus hospital was completed. According to the Stanford Medical History Center, the Women’s Auxiliary of the Palo Alto Hospital played an important role in raising funds needed for the facility:

In 1927 Stanford offered a plot of land on the Campus near El Camino Real for the new hospital and sentiment grew in the city to finance the operation. The plan was strongly endorsed by local doctors and the American Medical Association and in 1929 a $250,000 bond issue was approved by Palo Alto voters. The bonds covered only about half the cost of erecting the 100-bed, all-concrete structure which is still standing as the central portion of the old Palo Alto Hospital on the Stanford Campus. The money required to complete the building came from gifts by individuals and groups.

And, later, during the Great Depression they stepped in again:

The new hospital faced a problem common to many businesses throughout the nation. Patients simply didn’t have money to pay their hospital bills. To meet this problem, the Women’s Auxiliary began a program of making interest-free loans to patients.

The names of the women in the photograph are not known.

This image is No. 4 of 6 in a series of images featuring women throughout medical history. The images are from Stanford Medical History Center’s Flickr photo stream.

Previously: Gladys Louise Goselin with an unidentified baby, Mystery photo from Stanford Medical History Center, and Doctors and nurses in the operating room at Lane Hospital

Nutrition

Lisandra West

on November 24th, 2010

One more Thanksgiving post before you sit down to dinner: As you pile your plate high with turkey, sweet potatoes and green beans, you might also consider loading up on the cranberries. Why? Previous studies have shown cranberries may possess compounds that inhibit the growth of cancer and microbes, reduce inflammation and help the heart.

Here’s a look at what researchers have learned about this Thanksgiving staple:

- Cranberries are a source of natural anti-bacterial compounds called proanthocyanidins (PACs). Recent research at Worcester Polytechnic Institute has shown that PACs inhibit the ability of E. Coli bacteria to adhere to epithelial cells that line the urinary tract. Additionally, a review of Pubmed literature suggests that daily consumption of cranberries may help prevent recurrent urinary tract infection.

- Extracts and compounds isolated from cranberries can inhibit the growth and proliferation of a host of cancers including: breast, colon, prostate, and lung. Chemopreventive mechanisms induced by the fruit range from inhibition of enzymes whose aberrant activity in cells promotes cancer progression to induction of cancer cell death. See this review.

Of course, more research is needed to fully understand what health benefits cranberries might confer. But, for now, you can at least feel less guilty about indulging in an extra serving of the crimson fruit.

Previously: A guide to your Thanksgiving dinner’s DNA

Photo by prettyinprint

Humor

Lisandra West

on November 23rd, 2010

Two earlier posts looked at physicians who took care of patients at 30,000 feet. Here’s a new twist: What happens when there isn’t a doctor or nurse on board? Who takes care of a patient then?

I’m guessing that a soap opera star didn’t top your list. But, as I found out listening to a recent episode of NPR’s Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me, Guiding Light star Tina Sloan ended up pretending to be a doctor on just such an occasion:

I was on a plane coming from Phoenix and there was - somebody had a heart attack. And they came over the PA and said, is there a doctor onboard? Nothing. Is there a nurse onboard? Nothing. I had been a Nobel Prize winning cardiologist on another show. So I went up… I truly did. I truly said to the stewardess, I said, look, this guy’s in real trouble. I can say all the right words to him. You know, tell him about his blood pressure and the arrhythmia and calm him down until we get him down on the ground. But I said, you know, I’m not a doctor, but I played a Nobel Prize winning cardiologist.

So Sloan reassured the man who needed medical attention and helped him remain calm while until a real doctor arrived:

I did it. I swear I did it. I calmed him down. And I sat, you know, he was lying down on the ground, and I was talking to him and pretending I was taking his pulse and his blood pressure. And, you know, telling him that he was fine and that he was doing really well. And I did all the things that I was supposed to do.

Of course (and you already knew this), a soap opera star, however talented, is still not a substitute for professional medical attention.

Previously: When the call button calls: A hospitalist’s thoughts on delivering care at 30,000 feet, and When the call button calls, part two: Helping four patients in one round-trip transatlantic flight