Image of the Week, Stanford News

Lia Steakley

on May 5th, 2013

On Wednesday, Stanford Hospital & Clinics officially broke ground on a new 824,000-square-foot hospital at an event attended by 400 community members, donors, and administrators. As my colleague mentioned in an earlier Scope post, the new building “will feature amenities intended to enhance both physical and emotional healing with the latest in medical, surgical and diagnostic technology.”

This photo of bright red shovels being dug into ceremonial dirt that afternoon distinctly captures this exciting new chapter in Stanford’s history.

Previously: A new chapter for Stanford Hospital, Growing up: The expansion of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Hospital mock-ups help refine plans before construction begins and City of Palo Alto approves rebuilding and expansion of Stanford Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital

Photo by Norbert von der Groeben

Image of the Week, Neuroscience

Lia Steakley

on April 28th, 2013

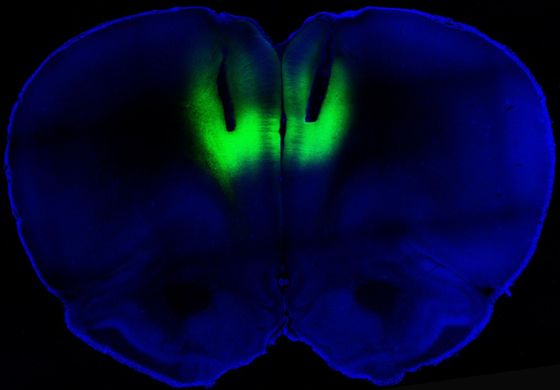

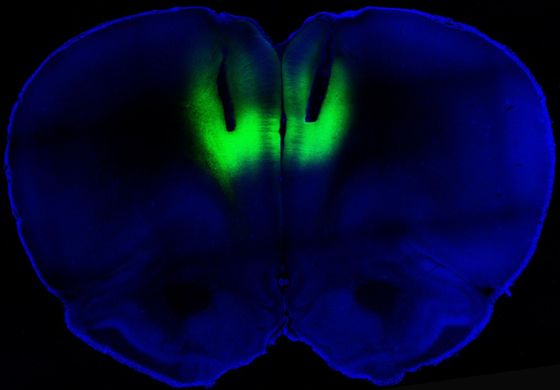

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health and University of California-San Francisco have found that stimulating a key part of the brain reduces compulsive cocaine-seeking and suggests the possibility of changing addictive behavior generally. NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, discussed the study, and the significance of the findings in a blog post earlier this month:

The researchers studied rats that were chronically addicted to cocaine. Their need for the drug was so strong that they would ignore electric shocks in order to get a hit. But when those same rats received the laser light pulses, the light activated the [prelimbic area of the prefrontal cortex], causing electrical activity in that brain region to surge. Remarkably, the rat’s fear of the foot shock reappeared, and assisted in deterring cocaine seeking. On the other hand, when the team used a different optogenetics technique to reduce activity in this same brain region, rats that were previously deterred by the foot shocks became chronic cocaine junkies.

Clearly this same approach wouldn’t be used in humans. But it does suggest that boosting activity in the prefrontal cortex using methods like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which is already used to treat depression, might help.

This image shows optogenetic stimulation using laser pulses illuminating the prelimbic cortex. The channelrhodopsins used to create the photo were provided to researchers by Stanford bioengineer Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD.

Previously: Better than the real thing: How drugs hot wire our brains’ reward circuitry, The brain’s control tower for pleasure and Addiction: All in the mind?

Photo by Billy Chen and Antonello Bonci

Image of the Week

Michelle Brandt

on April 21st, 2013

Every year on a Friday in spring, Stanford Medicine opens its doors to area high-schoolers, who take courses at the medical school on a wide range of medical and scientific topics. This photo from earlier in the week shows three participants of our popular “Brain Lab” session.

Previously: Image of the Week: Med School 101, Med school: Up close and personal, A quick primer on getting into medical school, Teens interested in medicine encouraged to “think beyond the obvious” and High-school students get a taste of med school

Photo by Norbert von der Groeben

Image of the Week, Imaging, Neuroscience, Research, Stanford News

Lia Steakley

on April 14th, 2013

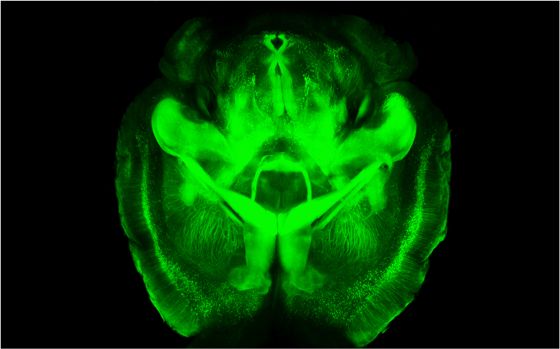

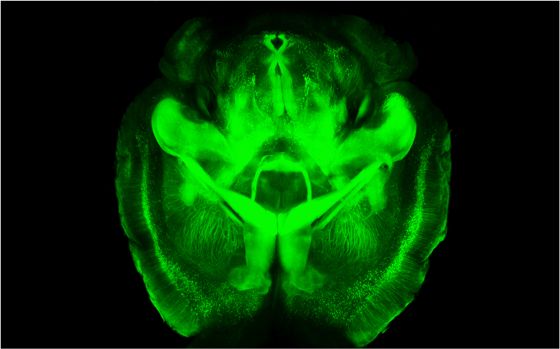

Earlier this week, fellow Scope contributor Bruce Goldman reported on a paradigm-shifting process developed by Stanford psychiatrist and bioengineer Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Using the process, called CLARITY, scientists were able to turn a mouse brain into an “optically transparent, histochemically permeable replica of itself.”

National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, commented on the breakthrough in a recent blog post, saying:

CLARITY is powerful. It will enable researchers to study neurological diseases and disorders, focusing on diseased or damaged structures without losing a global perspective. That’s something we’ve never before been able to do in three dimensions.

This haunting image depicts a three-dimensional rendering of clarified brain imaged from the ventral half. To fully experience the new method’s awe-inspiring capabilities, watch this fly-through video.

Previously: Scientific community (and Twitter) buzzing over Stanford’s see-through brain, Lightning strikes twice: Optogenetics pioneer Karl Deisseroth’s newest technique renders tissues transparent, yet structurally intact and Peering deeply – and quite literally – into

Photo by Deisseroth lab

Image of the Week

Lia Steakley

on April 7th, 2013

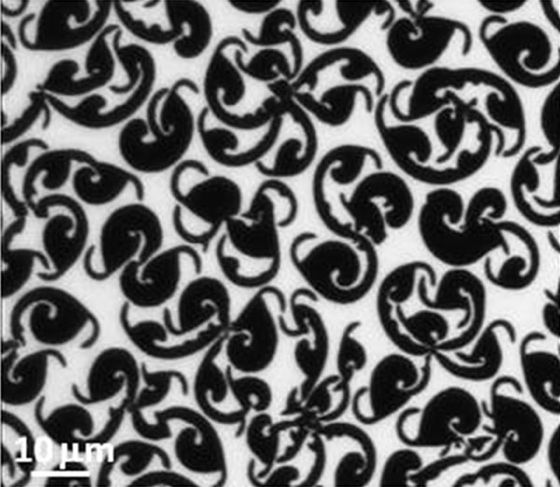

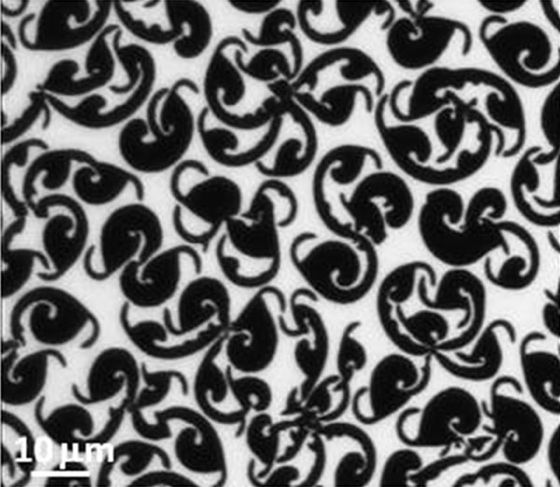

This microscopic image of lung surfactant, a lipid-protein material that reduces surface tension in the lung and aids in proper pulmonary function, could easily be mistaken for a whimsical textile print. A recent issue of Biomedical Beat provides more information about the fanciful designs represented in the image and how they may offer insights into developing new methods for drug delivery:

Using microscopy techniques, the researchers captured a snapshot of the changes that occur (black) when surfactant molecules are stressed by carbon nanoparticles. The scientists found that if inhaled, carbon nanoparticles could influence the function of the main lipid component of surfactant. A likely gateway for nanoparticles to enter the body is through the lungs, so this and future studies may help scientists improve drug delivery methods.

Photo by University of Kansas State

Image of the Week, Neuroscience, Stanford News

Lia Steakley

on March 24th, 2013

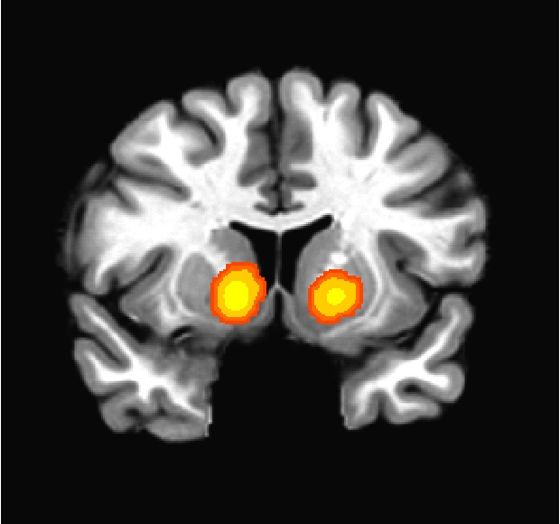

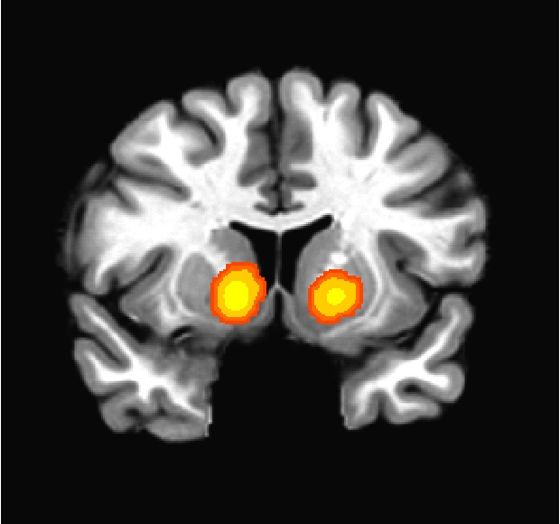

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) offers a way to gain important information about brain function and is commonly used by researchers to understand neurological activity. But a recent Stanford study shows that conventional methods of analyzing fMRI scans may “systematically skew which regions of the brain appear to be activating, potentially [biasing] hundreds of papers that use the technique.”

The research was conducted in the lab of Brian Knutson, PhD, associate professor of psychology, who studies reward processing in a small area of the brain known as the nucleus accumbens. A recent Stanford Report article offers more details about the researchers’ findings:

… [F]MRI has only been in use since the mid-1990s. Many of the most common analyses in use today are holdovers from older, lower-resolution types of imaging and seem to have some undesired effects on the finer-grained signals fMRI can provide.

Knutson and [Matthew Sacchet, a PhD student in the meurosciences program at the School of Medicine] found that when researchers process fMRI data with a traditional “smoothing kernel” of 8mm, they end up averaging their images over too large an area. Activity in smaller brain structures can then be overlooked, or even shifted to areas that receive more blood flow and where the blood oxygenation level-dependent signal is stronger.

“It might seem strange that a systematic bias like that could bias the whole field,” Knutson said. “But if half the people use 8mm and half use 4mm, you might end up with very different results, and it could add up.”

Sacchet, who provided the above image from the study, explains that the yellow, orange and red areas highlight “regions that are likely to be involved in reward anticipation when applying relatively large spatial smoothing. Hotter colors indicate higher probability of association.”

Previously: Genetics may influence financial risk-taking and Using neuroeconomics to understand how aging affects financial decisions

Image of the Week, Medical Education, Medical Schools, Stanford News

Lia Steakley

on March 17th, 2013

Two days ago, on Match Day, Stanford medical students, and others at institutions around the country learned where they’ll be heading to residency in July. In this photo, Stanford student Danica Lomeli hugs her father, Luis, while her mother, Diana, reacts to the news that Danica will be doing her residency in family medicine at UCLA.

This year’s class was particularly successful, with all 91 students matching, 70 percent receiving their first choice and 85 percent one of their top three choices. Students matched in 15 different states, with two-thirds divided between Massachusetts and California. Nineteen matched with Stanford residencies.

Previously: Good luck to medical students on Match Day!, My parents don’t think I’m smart enough for family medicine: One medical student’s story, Image of the Week: Match Day 2012, Match Day 2012 decides medical students’ next steps, A match made in heaven? Medical students await their fate and Brian Eule discusses Match Day book

Image of the Week

Lia Steakley

on March 10th, 2013

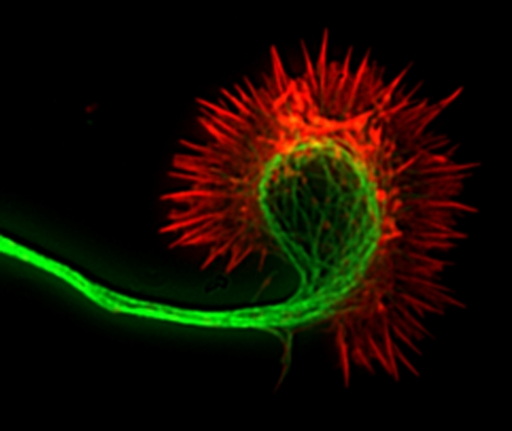

The average adult human body is composed of trillions of cells. Now imagine the complexities involved in trying to study the interworkings of these microscopic cells and determine what makes one part of a cell different from another. As Ars Technica reported earlier this week, scientists trying to accomplish this task face a number of challenges - but a team of researchers have developed a technique called magnetogenetics that could provide “a new way of seeing how different biochemical pathways behave when they are activated at a specific site within the cell.” John Timmer writes:

First, they created small, magnetic nanoparticles (a bit under 500nm across) coated with a chemical that is easy to link proteins to. By linking it to a fluorescent molecule, they showed that, with a small magnetic tip, they could maneuver it around inside cells with high efficiency. The particle would take a while to work its way through the cellular environment, however.

To actually manipulate the cell, the authors coated the particles with an activated form of a protein. Normally, the protein is used to organize movement by the cell. It does this by creating structures based on actin, a protein that polymerizes into long fibers that form part of the cell’s skeleton.

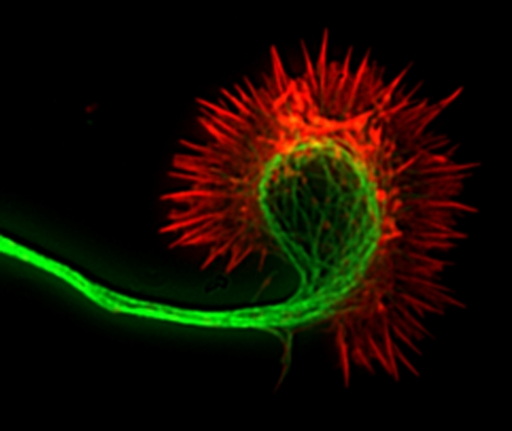

The stunning photo, which looks a bit like a plant form from a Dr. Seuss book, depicts the actin fibers of a nerve cell’s growing axon, which are shown in red.

Photo by National Institutes of Health

Image of the Week, Infectious Disease, Public Health, Research

Lia Steakley

on March 3rd, 2013

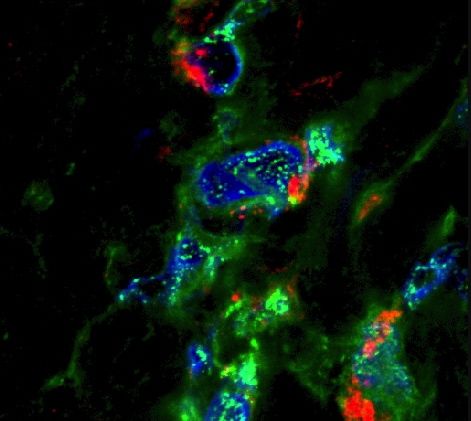

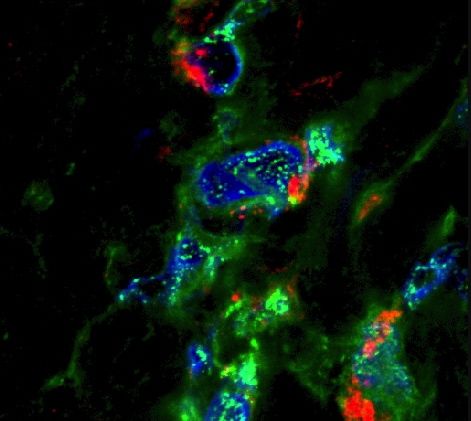

A University of California, Los Angeles study published online this week in Science offers clues about how various bacteria masquerade as viruses and, as a result, trick the immune system into using the wrong defense strategy. As explained in a university release, the bacteria manipulates the body into using a protein called interferon-beta to fend off its attack, but such an approach dose more harm than good:

Not only is interferon-beta ineffective against bacteria, but it can also block the action of interferon-gamma, to the advantage of bacteria. Further, if a real virus were to infect the body, triggering interferon-beta, it would divert the attention of the immune response, preventing an attack on the bacterial invader. The researchers say this may explain why the flu can lead to a more serious bacteria-based infection like pneumonia.

In the study, researchers used leprosy as a model to understand how bacteria can fool the immune system. Senor author Robert Modlin, MD, said the team opted to study leprosy because it “is an outstanding model for studying immune mechanisms in host defense since it presents as a clinical spectrum that correlates with the level and type of immune response of the pathogen.”

The above image shows leprosy bacteria marked in red and with the interferon-beta highlighted in green.

Photo by UCLA

Image of the Week, Imaging, Pediatrics, Pregnancy

Lia Steakley

on February 24th, 2013

By combining scans of healthy fetuses in the womb, including that of a woman who agreed to weekly electrocardiography scans starting at 18 weeks gestation until just prior to delivery, a team of UK-based researchers have created a 3D computerized model of the activity and architecture of human heart development. Their findings were published Thursday in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface Focus. According to a University of Leeds release:

Although [researchers] saw four clearly defined chambers in the foetal heart from the eighth week of pregnancy, they did not find organised muscle tissue until the 20th week, much later than expected.

Developing an accurate, computerised simulation of the foetal heart is critical to understanding normal heart development in the womb and, eventually, to opening new ways of detecting and dealing with some functional abnormalities early in pregnancy.

The above image shows an MRI scan of the heart of a 139-day-old fetus as seen from the top, with the muscle cells highlighted in red. An accompanying video illustrates fetal hearts at different stages of gestation.

Via Futurity

Photo by University of Leeds