Does it matter which parent your “brain genes” came from?

on May 7th, 2013 No Comments

Does it make a difference if a gene – or group of genes – is inherited from your mother or your father?

Does it make a difference if a gene – or group of genes – is inherited from your mother or your father?

That’s the question behind the study of genomic imprinting, a phenomenon in which a small percent of genes are thought to be expressed differently depending on which parent they came from. In particular, animal research suggests imprinting may affect aspects of brain development. Researchers wonder if genomic imprinting might explain differences in brain anatomy seen between men and women, such as men’s larger brain volumes.

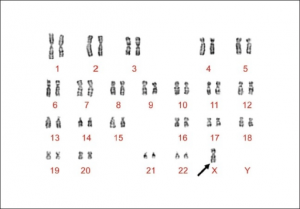

A new Stanford study, published today in the Journal of Neuroscience, adds to evidence that genomic imprinting is, in fact, happening in humans’ brains. The finding comes from MRI brain scans performed on a group of young girls with Turner syndrome, a chromosomal disorder in which a girl or woman has one missing or malfunctioning X chromosome. Turner syndrome gives an unusual opportunity to study genetic imprinting, because it allows comparisons of individuals who received a single X from Mom to those who got a single X from Dad. (The typical two-X-chromosome female body expresses a mosaic of Mom’s X and Dad’s X, making it impossible to tease apart the effects of the two parents. Males invariably get their single X chromosome from their mothers, so their cells always express the maternal X.)

The Stanford team, led by Allan Reiss, MD, documented several distinctions between the brains of Turner syndrome girls who have only a maternal X, those with only a paternal X, and typical girls with two X chromosomes, such as differences in the thickness and volume of the cortex, and in the surface area of the brain. The work helps clarify murky results from earlier studies of adults with Turner syndrome, the researchers say, because many adult women with Turner syndrome take estrogen supplements, which may have their own effects on brain development. None of the girls in the new study had taken estrogen.

The most tantalizing part of the paper is the scientists’ comment on the implications of their work for our general understanding of genetic imprinting. In part, they say:

By far, the most consistent finding with regard to sex differences in brain anatomy is the larger brain volume found in males compared with females. Although our groups did not differ on most whole-brain measures, our analyses revealed the existence of significant trends on total brain volume, gray matter volume and surface area, where these variables increased linearly from the Xp [paternal X] group being smallest, to the Xm [maternal X] group being largest, with typically developing girls in between. Considering that typically developing males invariably inherit the maternal X chromosome, while typically developing females inherit both and randomly express one of them in each cell, a linear increase in brain volume as seen in the present study is in agreement with what would be expected if imprinted genes located on the X chromosome were involved in brain size determination.

In other words, men may have their mothers to thank for their larger brains.

Karyotype image from a Turner Syndrome patient by S Suttur M, R Mysore S, Krishnamurthy B, B Nallur R - Indian J Hum Genet (2009).