‘Snorkel’ stents create lifeline to organs in method of treating complex abdominal aortic aneurysms

on January 15th, 2013 No Comments

It’s been called the chimney technique, and it’s been called the double-barrel technique. But Jason Lee, MD, prefers to call it the snorkel technique.

It’s been called the chimney technique, and it’s been called the double-barrel technique. But Jason Lee, MD, prefers to call it the snorkel technique.

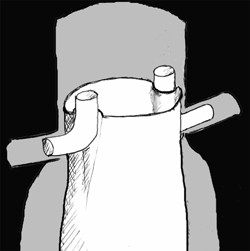

In the latest issue of Inside Stanford Medicine, I write about Lee, one of the most experienced physicians in the world at using this minimally invasive procedure to treat complex abdominal aortic aneurysms. In such cases, the aneurysm, a balloon-like bulge, extends very close to or beyond one or more of the aorta’s branch arteries, such as the renal arteries. This can make it challenging to use a stent graft, a small tube, to bypass the section of weakened arterial wall without obstructing blood flow to the branch arteries.

But Lee is able to circumvent this problem by placing one or more additional stents, which when deployed look like snorkels, adjacent to the main stent to create pathways for blood to reach branch arteries.

“The Europeans like to call this the ‘chimney graft,’ but in a chimney the smoke is going up, right?” Lee told me. “I don’t think that analogy is quite right because the blood for the kidney or visceral organ isn’t going up, like smoke, through a stent; it’s going down — like the vital air that comes down through a snorkel.”

Lee and Ronald Dalman, MD, have performed more than 60 snorkel procedures in the past three years, and my piece describes how they recently used the technique to treat Geraldine Vitullo, a 65-year-old grandmother from Visalia, Calif.

Schematic drawing of “snorkel” stents adjacent to main stent reproduced with permission from the Journal of Endovascular Therapy.