Stanford’s RISE program gives high-schoolers a scientific boost

on July 31st, 2012 No Comments

While a solution to low test scores and lackluster interest in science and engineering careers among schoolchildren nation-wide remains elusive, outreach initiatives can effect change at the local level. A Stanford Report article today describes the university’s Raising Interest in Science and Engineering (RISE) program, which matches select low-income and under-represented minority high-school students with expert guidance, work experience in laboratories, and exposure to a variety of academic and industry experiences. From the piece:

While a solution to low test scores and lackluster interest in science and engineering careers among schoolchildren nation-wide remains elusive, outreach initiatives can effect change at the local level. A Stanford Report article today describes the university’s Raising Interest in Science and Engineering (RISE) program, which matches select low-income and under-represented minority high-school students with expert guidance, work experience in laboratories, and exposure to a variety of academic and industry experiences. From the piece:

In many cases, minority and lower-income students who are particularly unprepared for and underrepresented in the sciences don’t even see a science or engineering degree as an option.

….

“These are kids who may not have scientists or engineers in their networks,” said Kaye Storm, MA, director of Stanford’s Office of Science Outreach, which runs RISE. “They know they like science or engineering, but they don’t really know what that might mean in terms of an internship or career.”

By exposing the students to an academic laboratory environment and introducing them to potential scientific contacts, RISE aims to bridge that gap between student talent and access to a college degree in the sciences.

All 89 students who have participated in RISE since the program’s 2006 inception have gone on to college or will enter it this year, and 12 have attended Stanford. RISE alumna Alison Logia tells writer Max McClure:

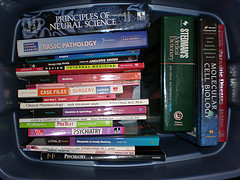

“In school, I’d end up in science classes with predesigned labs,” said Logia. “But when I came to Stanford it was different. When you get your results, you can’t look them up in a book to see if they’re correct, because no one’s ever done this experiment before.”

Logia, a graduate of Sequoia High School in Redwood City, worked for two summers in the lab of chemical engineering Professor Gerald Fuller [PhD]. Although she knew she was interested in math and science in high school, her experiences in the Fuller Lab taught her “how to work in a lab, how to talk to a professor,” and solidified her desire to go into engineering.

Previously: Stanford science program for teens receives Presidential Award, I know what you did this summer: High-school interns share their experiences at Stanford, A look at the Stanford Medical Youth Science Program and A prescription for improving science education

Photo by L.A. Cicero