Brain’s gain: Stanford neuroscientist discusses two major new initiatives

on April 30th, 2013 No Comments

The brain has gotten a lot of attention lately. Last month, President Obama announced a $100 million decades-long research initiative to “unlock”, as he called it, “the mystery of the three pounds of matter that sits between the ears.” And, in the arena of jaw-dropping science, Stanford’s Karl Diesseroth, MD, PhD, and Kwanghun Chung, PhD, recently unveiled CLARITY - a process that rendered a mouse brain transparent. Thomas Insel, MD, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, called the Stanford researchers’ work, “frankly spectacular.”

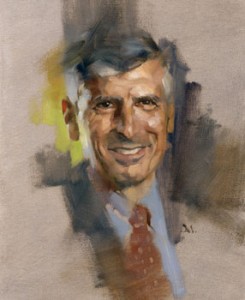

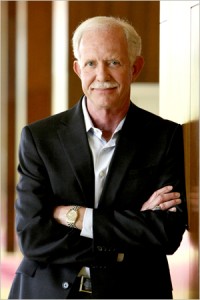

Primed for this moment of brain fame is Stanford’s Bill Newsome, PhD, who has been toiling in the field of neuroscience for nearly three decades. His international renown as a research scientist catapulted him to two new key brain posts: vice chair of the federal BRAIN initiative and director of a new interdisciplinary neuroscience institute at Stanford.

I talked with Newsome about both efforts for my latest 1:2:1 podcast. I began by asking him, “Why now?” What has propelled the brain to the front of the food chain in federal funding?

He called the Obama administration “prescient” for putting forth the federal effort. “There has never been a bigger moment of progress for brain research than there is now,” he told me. He describes this time as a “tipping point” where putting the pedal on the accelerator will make a whole new world of research possible.

Newsome is also cautious. Over-promising breakthroughs is clearly not in his vernacular. Yet he see this moment with clarity and admits that accelerating what we’re already doing will allow us “to get new data about the brain that we never dreamed possible.”

Previously: Co-leader of Obama’s BRAIN Initiative to direct Stanford’s interdisciplinary neuroscience institute, Lightning strikes twice: Optogenetics pioneer Karl Deisseroth’s newest technique renders tissues transparent, yet structurally intact, Experts weigh in on the new BRAIN Initiative and A federal push to further brain research