We’ve got your number: Exact spot in brain where numeral recognition takes place revealed

on April 16th, 2013 No Comments

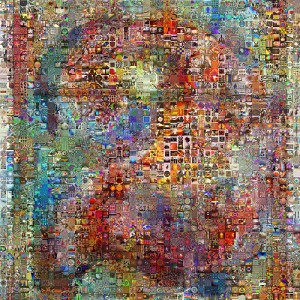

Your brain and my brain are shaped slightly differently. But, it’s a good bet, in almost the identical spot within each of them sits a clump of perhaps 1 to 2 million nerve cells that gets much more excited at the sight of numerals (“5,” for example) than when we see their spelled-out equivalents (“five”), lookalike letters (“5″ versus “S”) or scrambled symbols composed of rearranged components of the numerals themselves.

Your brain and my brain are shaped slightly differently. But, it’s a good bet, in almost the identical spot within each of them sits a clump of perhaps 1 to 2 million nerve cells that gets much more excited at the sight of numerals (“5,” for example) than when we see their spelled-out equivalents (“five”), lookalike letters (“5″ versus “S”) or scrambled symbols composed of rearranged components of the numerals themselves.

Josef Parvizi, MD, PhD, director of Stanford’s Human Intracranial Cognitive Electrophysiology Program, and his colleagues identified this numeral-recognition module by recording electrical activity directly from the brain surfaces of epileptic volunteers. Their study describing these experiments was just published in The Journal of Neuroscience.

As I explained in my release about the work:

[A]s a first step toward possible surgery to relieve unremitting seizures that weren’t responding to therapeutic drugs, [the patients had] had a small section of their skulls removed and electrodes applied directly to the brain’s surface. The procedure, which doesn’t destroy any brain tissue or disrupt the brain’s function, had been undertaken so that the patients could be monitored for several days to help attending neurologists find the exact location of their seizures’ origination points. While these patients are bedridden in the hospital for as much as a week of such monitoring, they are fully conscious, in no pain and, frankly, a bit bored.

Seven patients, in whom electrodes happened to be positioned near the area Parvizi’s team wanted to explore, gave the researchers permission to perform about an hour’s worth of tests. In the first, they watched a laptop screen on which appeared a rapid-fire random series of letters or numerals, scrambled versions of them, or foreign number symbols with which the experimental subjects were unfamiliar. In a second test, the experimental subjects viewed, again in thoroughly mixed-up sequence, numerals along with words for them as well as words that sounded the same (1″, “one”, “won”, “2″, “two”, “too”, etc.).

A region within a part of the brain called the inferior temporal gyrus showed activity in response to all kinds of squiggly lines, angles and curves. But within that area a small spot measuring about one-fifth of an inch across lit up preferentially in response to numerals compared with all the other stimuli.

The fact that this spot is embedded in a larger brain area generally responsive to lines, angles, and curves testifies to the human brain’s “plasticity:” its ability to tailor its form and function according to the dictates of experience.

“Humans aren’t born with the ability to recognize numbers,” says Parvizi. He thinks evolution may have generated, in the brains of our tree-dwelling primate ancestors, a brain region particularly adept at computing lines, angles and curves, facilitating snap decisions required for swinging quickly from one branch to the next.

Apparently, one particular spot within that larger tree-branch-interesection recognition area is easily diverted to the numeral-recognition activity constantly rewarded by parents and teachers during the numeracy boot camp called childhood.

Nobody can say those little monkeys don’t learn anything in kindergarten.

Previously: Metamorphosis: At the push of a button, a familiar face becomes a strange one and Why memory and math don’t mix: They require opposing states of the same brain circuitry

Photo by qthomasbower