Oh, yes, I know all about arachnophobia. As a little sister, I was a prime target for two older brother’s unmerciful teasing. They had me so freaked out that a subtle hand gesture mimicking a spider would send me into a fit of tears.

Having spent my life blaming them for this encumbrance, it’s a bit unsettling to read that the primary instigator might have been…my mother. My brothers simply picked up where she left off - at my birth.

If you missed it, MSNBC ran a fascinating story yesterday discussing how some researchers speculate that we may be delivered into this world programmed to fear scary critters. Specific scary critters:

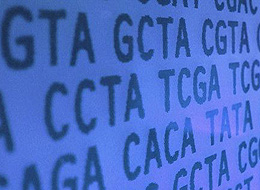

Scientists aren’t sure how the fear is passed down, but they speculate that stressful events like predator attacks trigger the release of a hormone in the mother that influences the development of the embryo.

Two researchers, Jonathan Storm, PhD, of the University of South Carolina Upstate in Spartanburg, and Steven Lima, PhD, of Indiana State University, figured this out by putting pregnant crickets into a terrarium containing a wolf spider. (They must both be older brothers.)

To make sure the spider didn’t eat the crickets, they put wax on its fangs. Thus, the spider could scare the bejeezus out of the crickets by stalking them - and probably gumming them - but the crickets would be left intact and able to produce offspring.

When the researchers compared the offspring of the freaked-out mothers to the offspring of the unfreaked-out mothers:

The differences were dramatic, the scientists said.

The newborn crickets whose mothers had been exposed to a spiderwere 113 percent more likely to seek shelter and stay there. They were also more likely to freeze when they encountered spider silk or feces - a behavior that could prevent them from being detected by a nearby spider. Overall, these newborns had better survival rates than other newborn crickets, eaten by the wolf spiders for the sake of science.

(Yeah, for the sake of science, and probably as payback for having their fangs waxed.)

This is really interesting stuff. It makes sense that we might be hardwired to fear spiders and snakes, but how is it that the cricket offspring knew that they should specifically fear spiders? The hormones released by the mother must be full of amazing information just waiting to be decoded by researchers.

Photo by Thomas Shahan