Society is increasingly becoming more data-driven. Noting the power of vast reservoirs of public information, the federal government launched the Big Data Research and Development Initiative — a $200 million commitment to “greatly improve the tools and techniques needed to access, organize and glean discoveries from huge volumes of digital data.” And the National Institutes of Health expanded its stake in the federal initiative in hopes of speeding up the translation of biomedical discoveries into bedside applications.

Society is increasingly becoming more data-driven. Noting the power of vast reservoirs of public information, the federal government launched the Big Data Research and Development Initiative — a $200 million commitment to “greatly improve the tools and techniques needed to access, organize and glean discoveries from huge volumes of digital data.” And the National Institutes of Health expanded its stake in the federal initiative in hopes of speeding up the translation of biomedical discoveries into bedside applications.

In an effort to bring together innovative thinkers from information-technology corporations, startups, venture-capital firms and academia to capitalize on the wealth of opportunities using data-mining in biomedicine, Stanford Medicine and Oxford University are sponsoring a three-day conference from May 22-24. Curious to know more about the event and promise of big data, I reached out to Atul Butte, MD, PhD, Stanford systems-medicine chief and the conference’s scientific program committee chair. Below he shares why he’s passionate about how data-mining can transform scientific research and health care and discusses the conference program.

A recent Stanford Medicine article called data-mining the “fastest, least costly, most effective path to improving people’s health” that you know. Can you explain why you believe this to be the case?

Data-driven science, or data-mining, works faster and effectively because we are already sitting on billions of measurements made across the health system! Every time a physician orders a medication, every time a nurse or pharmacist dispenses a drug, every time a blood test is performed, every x-ray or CT scan that’s performed… all of this information ends up in a database today. So the part of science or innovation that involves collecting the measurements is actually the easiest part now, because the measurements are already there, just waiting for the right question to be asked.

In the same article, you said “hiding within [existing] mounds of data is knowledge that could change the life of a patient, or change the world” - and that if you didn’t analyze those data or show others how to, you feared no one will. How did you grow so passionate about this area?

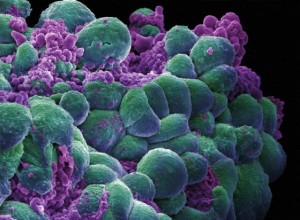

I think we in the biomedical field make these measurements, but we often don’t realize how these measurements can interrelate or be used together. Our example from one of our recent articles was on our use of two big sets of public data. One set covered the molecular changes seen in tissues affected by diseases, and another set covered the molecular changes seen in cells treated by drugs. We realized that we could partner just these two public data sets together, to get new ideas of what other diseases might be treatable by these drugs. And, we could do this in a purely computational approach – an approach that is nearly infinitely scalable to more diseases, more investigators and more ideas. When I see hard working investigators working tirelessly to make highly accurate and significant measurements, but so few people taking advantage of that data, I can’t help but be passionate!

Earlier this year, you published a study, which involved combing through large amounts of data, to find that beta carotene may protect people with a common genetic risk factor for type-2 diabetes. Can you describe other recent findings that have stemmed from researchers’ use of this “big data” approach?

Stanford professor Russ Altman, MD, PhD, and his team recently showed how search engine logs can be mined to discover side effect of release drugs that might not have shown up during the initial clinical trials on those drugs. Similarly, Nigam Shah, MBBS, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, showed how similar side effects for drugs are sitting in physician clinical notes. Both text-based clinical notes and search engine logs are massive sources of big data that to date have barely been tapped for medical research.

What was the catalyst for launching the Big Data in Biomedicine conference?

The Li Ka Shing Foundation has played the leading role in bringing us together with Oxford University in planning events on big data. Our first, smaller conference was held in Oxford last November. Based on the success of that event, we realized we could host a larger conference at Stanford and open it up to the public. We couldn’t have done this without the support of the Li Ka Shing Foundation.

Continue Reading »

Daily text messages may be an effective option to help children with asthma manage their symptoms and reduce doctor visits, according to recent research from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Daily text messages may be an effective option to help children with asthma manage their symptoms and reduce doctor visits, according to recent research from the Georgia Institute of Technology.