You see? Just like I said… Nicholas Carr thinks so, too.

Tuesday, May 31st, 2011“I think as a society we’re choosing information overload: we’re choosing to sacrifice the more meditative and contemplative aspects of our minds.”

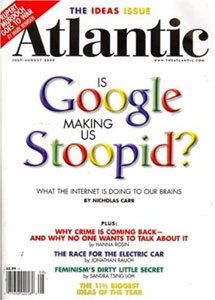

I wrote on just this subject a few days ago, in a post entitled “Are We ‘Outsourcing Our Brains to the Cloud?’” – then I ran across the latest from technology writer Nicholas Carr, who appears to agree, as shown in his comment above. His latest book, The Shallows, discusses what he fears the Internet is doing to our brains. It’s sold 50K hardbacks in the U.S. alone – that’s real books, with paper pages.

Carr, the blogger behind Rough Type and the author of the controversial Atlantic article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” got his first PC back in the 1980s and was an avid net user until “a few years ago, I noticed some disturbing changes in the way my mind worked. I was losing the ability to concentrate.” According to the AFP article:

While the Internet has enormous benefits in delivering incredible amounts of information at incredible speed, it’s also a distracting and interruption-rich environment.

Carr said it encourages quick shifts in focus – and discourages sustained attention and the ability to think deeply and creatively about one topic and to challenge conventional wisdom.

Carr concluded, “We take in so much information so quickly that we are in a constant state of cognitive overload.” He added that “multitasking erodes cognitive control. We lose our ability to say that this is important, this is unimportant. All we want is new information.” However, when we open a real book with real pages, “there’s nothing else going on except words on a page, no distractions. It helps train us to be deep thinkers.”

Over at Books Inq., my previous column generated a few comments. Frank Wilson hoped we could find a sort of middle way: “I think the problem is real, at least potentially. I just think we may be making too much of it. I have noticed, now that I have returned to work, that my memory is sharper for some reason. I think may be we just have to make some time to do things the old-fashioned way, things like memorizing poems. The way we still make bread, though we can buy it at the store.”

Over at Books Inq., my previous column generated a few comments. Frank Wilson hoped we could find a sort of middle way: “I think the problem is real, at least potentially. I just think we may be making too much of it. I have noticed, now that I have returned to work, that my memory is sharper for some reason. I think may be we just have to make some time to do things the old-fashioned way, things like memorizing poems. The way we still make bread, though we can buy it at the store.”

I hoped so, too. But so far, Carr hasn’t had much success:

Carr admitted he himself has not had great success in limiting the time he spends online. But the biggest change he made as a writer and researcher was to use the web only to track down source material.

“Then I’d make an effort to actually read those things in print. I did find that made a big difference in my ability to be attentive and a thorough reader and hopefully a deeper thinker.”

But Carr said it was not just a matter of individual choice. If friends, colleagues and employers were constantly on line, “then you feel in many ways compelled to do so even if you don’t want to, because you don’t want to damage your career or your social life”.