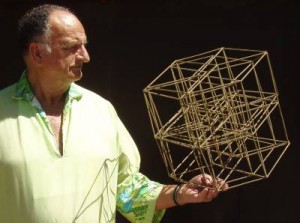

Reading at St. Catherine's Church, Kraków (Photo: Droid)

In an early poem, Bei Dao wrote, “freedom is nothing but the distance/between the hunter and the hunted.”

All too true, as he soon found out.

Protesters once shouted his poems in Tiananmen Square, and after his exile (he had been in Berlin during the 1989 uprising), he continued to write in Scandinavia, the U.S., and France. He now teaches at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, since the government allowed his return to the PRC a few years ago.

At last month’s Czesław Miłosz Festival in Kraków, he participated in a panel called “Place of Birth” with Lithuanian Egidijus Aleksandravičius, English Timothy Garton Ash, and Polish Irena Grudzińska Gross, hosted by Italian Francesco Cataluccio. Although some of the estrangements from native realms were more voluntary than others, the team discussed their sense of displacement from homeland.

But the most haunting words of the evening belonged to Bei Dao: “It’s mysterious. Why do we think about birthplace, mother tongue, the origin of life?” he asked. And then he gave his answer.

“Each language keeps the secret code of a culture,” he said.

“China is unified by a written language,” he said. “The local accent keeps their secret, keeps their code.” That’s what he cherishes, and that is what the world is most at risk of losing.

His words returned to me today as I read an unusually eloquent McClatchy Newspapers article, “Silenced Voices,” by Tim Johnson:

Some linguists say that languages are disappearing at the rate of two a month. Half of the world’s remaining 7,000 or so languages may be gone by the end of this century, pushed into disuse by English, Spanish and other dominating languages.The die-off has parallels to the extinction of animals. The death of a language, linguists say, robs humanity of ideas, belief systems and knowledge of the natural world. Languages are repositories of human experience that have evolved over centuries, even millennia.

“Languages are definitely more endangered than species, and are going extinct at a faster rate,” said K. David Harrison, a linguist at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and the author of the book When Languages Die. “There are many hundreds of languages that have fewer than 50 speakers.”

Language is an invisible triumph of humanity, and its disappearance brings only silence.”It’s not as flashy as a pyramid, but it represents enormous human achievement in terms of the thought and effort that went into it,” said Daniel Suslak, a linguistic anthropologist at Indiana University…

Miłosz knew this: This is why Miłosz wrote in Polish throughout his 40 years of exile in California, said the Chinese poet.

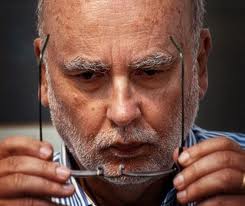

In 1999 at Stanford (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

Bei Dao was born in 1949 in Beijing. “As Chairman Mao declared the birth of the People’s Republic of China from the rostrum in Tiananmen Square, I was lying in my cradle no more than a housand yards away. My fate seems to have been intertwined with China ever since,” he wrote in the festival’s 100-page companion book. “I received a privileged, but brief, education. I was a student at the best high school in Beijing, until the Cultural Revolution broke out in 1966. All the schools were closed, and three years later I was assigned to work in the state-run construction industry.”

In those harsh circumstances, at the age of 20, the young construction worker began to write at a site in the mountains more than 200 miles from Beijing.

During the conference session, he recalled visiting his dying father in a brief respite from exile, but Beijing was a disappointment: “It was not my city anymore.”

“The Chinese people do not know how to rebuild,” he said, praising the preservation of Venice and Florence. The Chinese, by contrast, “build like Las Vegas – very, very ugly buildings.”

Left to right: Francesco Cataluccio, Bei Dao, Timothy Garton Ash, Egidijus Aleksandravičius, Irena Grudzińska Gross (Photo: my Droid)

“We were drawn by the concept of progress from the West and from Marxism. Progress became the canon for Chinese people. There was more attention on GDP and new buildings. Materialism and consumption destroyed Chinese culture.”

At Stanford over a decade ago, he remarked, “I don’t have a motherland now.”

“Someone recently said to me that I am like a man to whom the whole world has become a foreign country, and I like that.”

But things change, in our heads as well as in the world.

Detroit, the notorious city of my birth, is now as much a gutted ruin if it had been destroyed by enemy mayhem – which in a sense it had been. And as some of the speakers mourned their lost homes, I wondered if they were actually mourning the passage of time as much as they were exile and upheaval.

Political exile is poignant, but disguises a more inexorable reality: We are exiles in time as well as in space. Both are excruciatingly transient.