Edward Hirsch and wild gratitude

Tuesday, March 30th, 2010

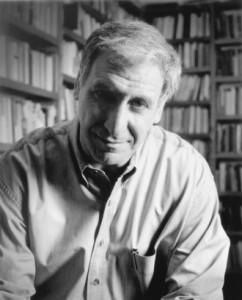

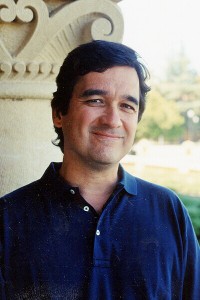

Hirsch (Photo: E. Thayer)

Edward Hirsch wears a number of hats: Some think of him as president of the Guggenheim Foundation. Some think of him primarily as an essayist, whose work has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, American Poetry Review, and The Paris Review, and the author of a weekly column on poetry for the Washington Post Book World from 2002 to 2005. My association is entirely different: While on the faculty at the University of Houston with Adam Zagajewski, he shepherded American students to Poland to acquaint them firsthand with the wellspring of some of the greatest poetry of the 20th century, including making arrangements for the kids to meet Nobel poet Czeslaw Milosz.

But if he’s like most poets, Hirsch would rather be remembered for his verse. On Sunday, the New York Times offered a rather enticing hors d’œuvre for Hirsch’s upcoming visit to Stanford in a review here.

The review, by Peter Campion, discusses the title of Hirsch’s new and selected, The Living Fire, taken from his poem “Wild Gratitude”:

On its surface, the poem seems to be about, well, a guy spending time with his cat. But as he listens to her “solemn little squeals of delight,” he begins to remember the 18th-century English visionary and madman Christopher Smart, who in his most famous poem, “Jubilate Agno,” venerated his own cat, Jeoffry. The memory leads to a chain of associations, and the poem ends in a nearly epiphanic moment:

And only then did I understand

It is Jeoffry — and every creature like him —

Who can teach us how to praise — purring

In their own language,

Wreathing themselves in the living fire.This passage could stand as an emblem for all of Hirsch’s poetry. Literary and allusive, but also domestic and intimate, as it rises toward praise, Hirsch’s voice resounds with both force and subtlety.

(Vis-à-vis Kit Smart’s madness and eventual confinement in an asylum, see Samuel Johnson: “I did not think he ought to be shut up. His infirmities were not noxious to society. He insisted on people praying with him; and I’d as lief pray with Kit Smart as any one else. Another charge was, that he did not love clean linen; and I have no passion for it.”)

Hirsch will be coming to Stanford on Monday, April 26. Stay tuned.

she worried.

she worried.