Bad book reviews = great sales?

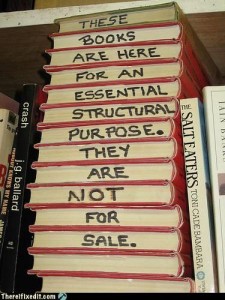

Sunday, February 27th, 2011 The conventional wisdom in the book biz has always been that any publicity is good publicity — and a spectacular, jeered-at failure is a better option than a quiet, well-respected success reviewed only in the Journals That Count. Even more so now, when the biggest risk is that your book will float away in the receding tsunami of seasonal offerings.

The conventional wisdom in the book biz has always been that any publicity is good publicity — and a spectacular, jeered-at failure is a better option than a quiet, well-respected success reviewed only in the Journals That Count. Even more so now, when the biggest risk is that your book will float away in the receding tsunami of seasonal offerings.

This Stanford study by two business professors confirms the conventional wisdom — to a point. Bad reviews can dramatically boost sales for obscure and up-and-coming writers. They don’t help the famous.

“Any publicity is not always good publicity, as the old adage goes,” Wharton’s Jonah Berger told the Stanford Daily. “But there were also cases where even negative publicity seemed to help sales, so it was interesting to think about when it helps versus hurts.”

The study, co-authored by Berger and Stanford’s Alan Sorenson, first examined a 2001-2003 dataset of weekly national sales for 244 fiction titles reviewed by The New York Times. The size of sale spikes in the week following the release of each book review showed that positive publicity benefited all titles and the bad publicity only helped lesser-known and obscure authors.

The second part of the study looked at how bad publicity impacted well-known and obscure books over time. Subjects looked at glowing and nasty reviews for a well-known book by John Grisham and then reviews for an invented title.

Those who read bad reviews of well-known books were less likely to buy the book. Negative reviews of unknown books, however, did not affect whether or not the subject was likely to purchase it.

“Let’s say you’ve got bad publicity or bad press on one of your new brands,” Stanford business professor Baba Shiv said. “On one hand, it’s making your brand look familiar, which is associated with positive emotion and at the same time, it’s eliciting negative emotion towards the brand, which comes from the bad publicity.”

“Let’s say you’ve got bad publicity or bad press on one of your new brands,” Stanford business professor Baba Shiv said. “On one hand, it’s making your brand look familiar, which is associated with positive emotion and at the same time, it’s eliciting negative emotion towards the brand, which comes from the bad publicity.”

The studies depended on emotional “decay rate”– how quickly an emotion (both good or bad) fades away. Stanford business professor Baba Shiv explained: “In the case of a well-known brand, the familiarity is already there … the decay rate of negative emotion will be much slower.” (Via Sarah Weinman)

The key point was that familiarity with the authors helped everyone, and familiarity was such a strong positive that it dissipated much more slowly in consumers’ minds than the bad taste of a critic’s diss. But the well-known books and authors already had the boost of familiarity — so the bad reviews could only hurt.

Read it here if you want to figure it out better than I have.

Of course, I wonder who is classifying a review is good or bad — most are kind of mixed, aren’t they? And for myself, I’d much rather read a interesting failure — a profound book that failed in some key way, than a very well-reviewed lightweight book. And name recognition is measured … how?

For another take on reviewing, read about Owl Criticism (hat tip, Frank Wilson). Charles Baxter takes on amazon-type online reviews, accusing them of “Owl Criticism”: “With Owl Criticism, you have statements like, ‘This book has an owl in it, and I don’t like owls.’”

Frank’s reaction to Baxter is worth reading, too: it’s here.