Eros as delusion: Poet Helen Pinkerton tips her hat to Thomas Aquinas (and Yvor Winters)

Sunday, July 31st, 2011Helen Pinkerton‘s interview in Think Journal, “The Love of Being,” starts out slowly – but by the time she gets to Thomas Aquinas, she’s on a tear.

The octogenarian poet came from hardscrabble upbringing in Montana. Her father died in a mining accident when she was 11, leaving her mother with four children to raise – well, if you want that story, you can read it in my own article about her here.

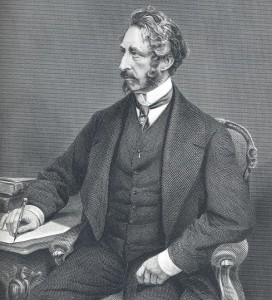

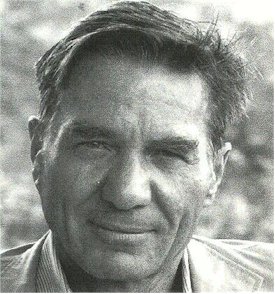

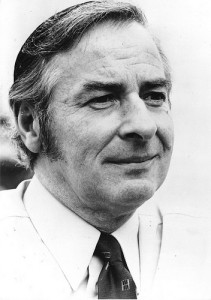

Then, she landed at Stanford, where she was one of Yvor Winters‘ inner circle, along with folks like Janet Lewis, Thom Gunn, Edgar Bowers, Turner Cassity, and J.V. Cunningham. Although she intended to be a journalism major, her plans changed abruptly: “Winters’ level of teaching, the kinds of topics he expected us to write about, the seriousness of his consideration of literary and philosophical questions of all sorts simply brought out in me a whole new capacity for thinking and writing.” After that, and a course on narrative with Cunningham, she launched an alternative career as a poet and a Herman Melville scholar, too.

After that experience, Pinkerton found that her subsequent graduate work at Harvard “was a breeze and made little mark on me as a poet or a scholar.”

Winters described Pinkerton’s poetry as “profoundly philosophical and religious,” and she discusses how Ben Jonson scholar William Dinsmore Briggs led her in that direction, though she never met him – his teaching on medieval and Renaissance learning “permeated” the work of Winters and Cunningham, she said. Helen became preoccupied with the Thomistic notion of esse, and sees “nothingness” as the primary temptation of humankind. Hence, her poem, “Good Friday” (included in her book Taken in Faith), which claims:

Nothingness is our need:

Insatiable the guilt

For which in thought and deed

We break what we have built.

But more than temptation – it is delusion. “The chief aspect of the drive is the metaphysical assertion that nothingness is the real reality – that there is no real being.”

She links this drive with the thinking of the 19th and 20th century, particularly romanticism, which she sees as a drive toward annihilation. “Real love is the love of being. Eros is the love of non-being”:

I found my way out of it by grasping the Thomistic idea of God as self-existent being. There is no nothingness in reality. It is a kind of figment of the imagination. To believe that there is is a verbal trick – a snare and a delusion. Much of modern philosophy (Hegel, the Existentialists, et al.) are caught up in this delusive state of consciousness.

I do scorn and critique (always) “romantic religion” – or the religion of eros … as I call it – and I did see in others, as well as in myself – a pervasive “unavowed guilt” in our culture – based on an unavowed longing for “nothingness.” This is a kind of obsession of mine in my early thinking (and consequently in my poems) after I came to a realization of the nature of my consciousness. What was driving me to be dissatisfied with everything and everyone, including myself, was this “eros,” this craving for extremes of feeling, for a kind of perfection in things and in others.

Patrick Kurp has written some lovely stuff about Helen at Anecdotal Evidence – here, and here, and here … oh, just type “Pinkerton” into his search engine. There’s lots. I’m proud to have introduced them.

Meanwhile, an Yvor Winters reading was always mesmerizing. You can get a taste of it in this recording from San Francisco’s Poetry Center on Valentine’s Day, 1958: