A record: 140 pounds of books and two birds in a box

Friday, February 26th, 2010

Glen Worthey and Chris Bourg discuss the topic of the day: books. (Credit: L.A. Cicero)

The Stanford Humanities Center held its annual “book celebration” on Tuesday, toting up the numbers for scholarly output.

The total take for humanities the last year was 114 physical books (and the laminated covers of two books that were unable to join the gathering), 9 binders of sheet music representing one digital publication of the 9 symphonies of Beethoven, 2 music CDs, 1 movie, 1 video weblink, 1 link to the Nine Symphonies of Beethoven (which is the same as the 9 binders of sheet music), 1 folder of playbills, and other material related to over 50 productions of a Mark Twain play (including one play in Romanian, video included), 1 scroll, and 1 box with two birds.

The total weight of all of this material (excluding the birds in the box) was a record 140 pounds. The total number of pages is a whopping 41,345. And this of course doesn’t count the hours of musical and video material – or the scroll and the birds in the box…

Last year’s total was 70 books, weighing 78.25 pounds and including 20,883 pages. So this is nearly an 80 percent increase in weight – and a 98 percent increase in pages. However, if you correct (as the economists say) for Shelley Fisher Fishkin’s 29 volume edition of the works of Mark Twain – the numbers adjust to 113 pounds and 29,314 pages — an increase of only 44 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

Stanford President John Hennessy was unpleasantly buoyed by the “incredibly prolific year,” nothing that “the humanities are truly extraordinary”: “When the income goes down, the output goes up,” he crowed. After a little scholarly coughing around the room (much of it inaudible), German music scholar Stephen Hinton finally offered that “some of the projects may have been started in fatter times.”

In the spirit of university cost-cutting, the variety show style entertainment was “outsourced” to drama students, who had created to two sparky little songs on the perils of a life dedicated to the humanities.

Derek Miller, right, and Mason Flink on piano entertain the crowd with songs lampooning the humanities as subject and profession at the humanities hoedown. Local luminaries were on hand: That's author Marilyn Yalom in the red coat, Aron Rodrigue next to her, Matthew Tiews behind them. John Hennessy is over Aron's shoulder, Stephen Hinton, next to him, looks unamused in a gold-colored shirt. Charles Junkerman listens as he quaffs his chardonnay. Joseph Frank, author of the acclaimed 5-volume Dostoevsky series, sits with his walker; wife Marguerite whispers to him. Dagmar Logie also keeps him company. John Felstiner, author of "Can Poetry Save the Earth?" stands in the doorway. (Credit: L.A. Cicero)

Just in time for George Washington’s birthday: Edith B. Gelles Abigail & John: Portrait of a Marriage has been named one of three finalists for the $50,000 George Washington Book Prize — the largest prize for a book on early American history, and one of the largest literary prizes of any kind. The judges noted that Gelles’s book is “not only a lively telling of a most important chapter in our nation’s history, but also – and appropriately – a romance.” Gelles began her research into the Adamses over thirty years ago and is the author of Abigail: Portia: The World of Abigail Adams (1992), a co-winner of the American Historical Association’s Herbert Feis Award, and Abigail Adams: A Writing Life (1998), an examination of Abigail’s life through her letters.

Just in time for George Washington’s birthday: Edith B. Gelles Abigail & John: Portrait of a Marriage has been named one of three finalists for the $50,000 George Washington Book Prize — the largest prize for a book on early American history, and one of the largest literary prizes of any kind. The judges noted that Gelles’s book is “not only a lively telling of a most important chapter in our nation’s history, but also – and appropriately – a romance.” Gelles began her research into the Adamses over thirty years ago and is the author of Abigail: Portia: The World of Abigail Adams (1992), a co-winner of the American Historical Association’s Herbert Feis Award, and Abigail Adams: A Writing Life (1998), an examination of Abigail’s life through her letters. Joseph Frank writes in The New Republic about Dan Vittorio Segre’s

Joseph Frank writes in The New Republic about Dan Vittorio Segre’s

Kotodama: The spirit of language, the magical power that adheres to language.

Kotodama: The spirit of language, the magical power that adheres to language. pattern. “Part of me was in the 7th and 8th century, the other part of me was in late 20th century Tokyo,” he recalled.

pattern. “Part of me was in the 7th and 8th century, the other part of me was in late 20th century Tokyo,” he recalled.

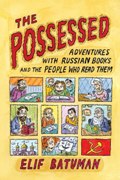

stories, mutter “We don’t mess with your ‘I-Ching’ “; and there’s a dinner “straight out of Dostoyevsky” in which Batuman and Freidin get the evil eye from a vain English translator in whose acclaimed Babel collection edition they have discovered mistakes. Yet even this isn’t the marvelous climax of the dinner, which comes when Babel’s daughter by his first wife stares at Babel’s second wife and shouts “THAT OLD WITCH WILL BURY US ALL.”

stories, mutter “We don’t mess with your ‘I-Ching’ “; and there’s a dinner “straight out of Dostoyevsky” in which Batuman and Freidin get the evil eye from a vain English translator in whose acclaimed Babel collection edition they have discovered mistakes. Yet even this isn’t the marvelous climax of the dinner, which comes when Babel’s daughter by his first wife stares at Babel’s second wife and shouts “THAT OLD WITCH WILL BURY US ALL.”