Happy birthday, Les Misérables! No, no – not the musical, the book

Thursday, May 31st, 2012It was, perhaps, my first love affair.

How old was I? Ten, eleven, maybe?

It was the book I read late at night, pushing a blanket under the crack under my bedroom door, so my father wouldn’t see the light in my room and know I was still awake until the wee hours. (I lived in fear that he might go outdoors, and see the lamplight blazing from the second-story window.) I lugged Victor Hugo‘s tome outdoors as during school recess in the bone-numbing Michigan winter, while my teachers tried to drive me into the group sports that made one “well-rounded.” If I were 12 and not 11 (can’t recall, really) it would also have my secret companion while the teacher droned – carefully hidden half-inside the desk, so it could easily be shoved inside should the teacher begin patrolling the aisles. It was the touchstone of my youth.

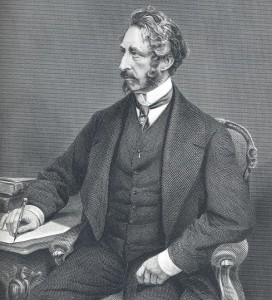

Happy birthday, Les Misérables. This year celebrates the 150th year since the book’s publication in 1862.

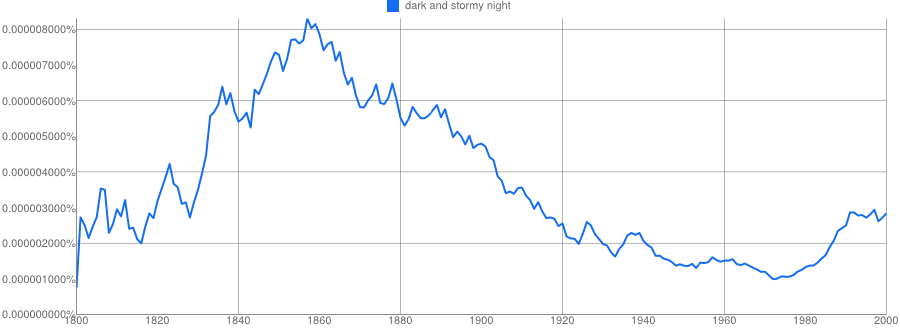

Clearly, I was not the only enthusiast. Although it was scathingly reviewed, it was a popular success. According to Graham Robb’s 1997 biography (a long excerpt is at “A Practical Policy” here):

By the time Parts II and III appeared on 15 May, it was clear that Hugo had achieved the impossible: selling a work of serious fiction for the masses, or, for the time being, inspiring the masses with a desire to read it. It was one of the last universally accessible masterpieces of Western literature, and a disturbing sign that class barriers had been breached. The oxymoronic opinions of critics betray the unease created by Hugo — that the lower orders might also have their literature: ‘a cabinet de lecture novel written by a man of genius’, according to Lytton Strachey half a century later, still fighting ‘bad taste’. In other words, Les Misérables was a jolly good book, but Victor Hugo never should have written it.

The view from the street was an inspiring contrast. At six o’clock on the morning of 15 May, inhabitants of the Rue de Seine on the Left Bank woke to find their narrow street jammed with what looked like a bread queue. People from all walks of life had come with wheelbarrows and hods and were squashed up against the door of Pagnerre’s bookshop, which unfortunately opened outwards. Inside, thousands of copies of Les Misérables stood in columns that reached the ceiling. A few hours later, they had all vanished. Mme. Hugo, who was in Paris giving interviews, tried to persuade Hugo’s spineless allies to support the book and invited them to dinner; but Gautier had flu, Janin had ‘an attack of gout’, and George Sand excused herself on the grounds that she always over-ate when she was invited out. But the nameless readers remained loyal. Factory workers set up subscriptions to buy what would otherwise have cost them several weeks’ wages.

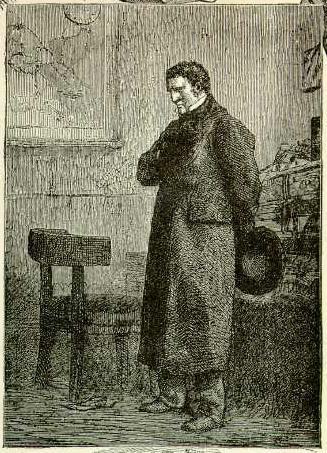

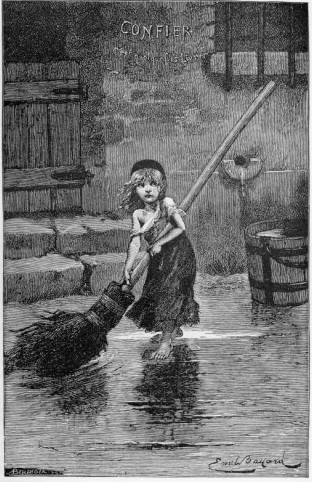

What impressionable girl would not fall in love with Jean Valjean? Of course, my role model was not Valjean, but rather Cosette, the milky, demure girl with sweetness of temperament. But some messages are enduring and subliminal: the heart of the book is a love story, but not a sexual passion between a man and a woman, but the pure devotion of a middle-aged man for the orphaned girl he had adopted. That, in itself, made it a good influence on a gawky, prepubescent girl – for other loves prove more enduring and reliable than the merely passionate ones. And mankind’s universal refusal to extend charity towards its weakest members would be a durable lesson.

According to Robb:

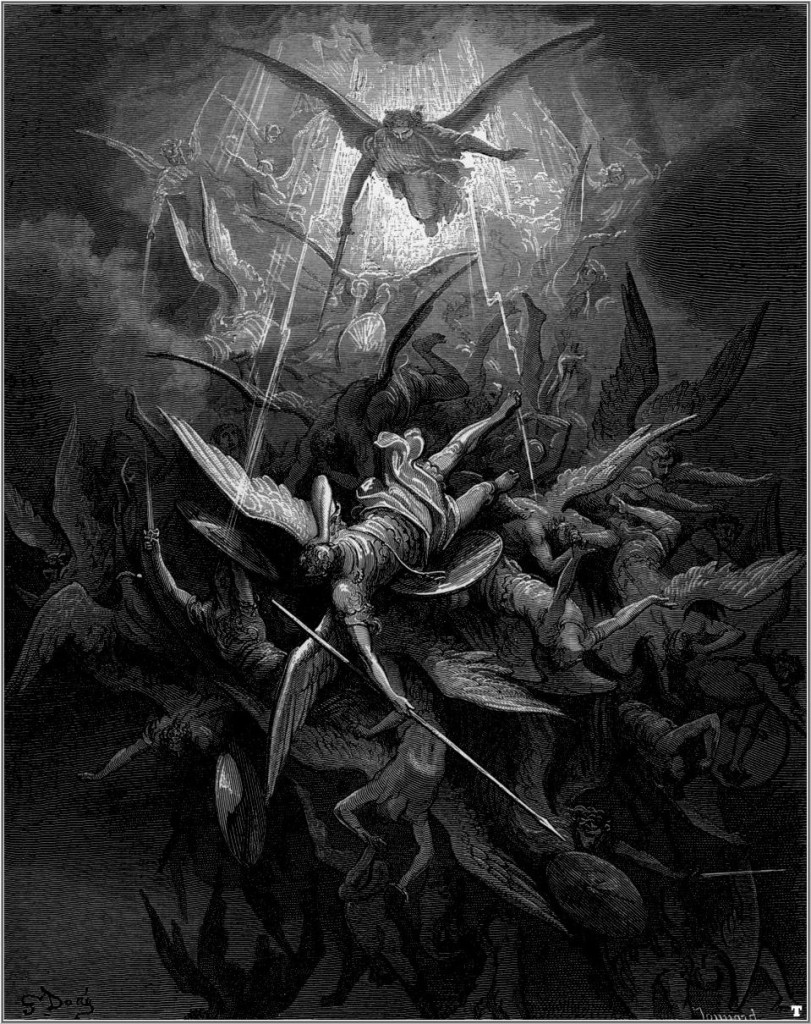

Les Misérables etches Hugo’s view of the world so deeply in the mind that it is impossible to be the same person after reading it — not just because it takes a noticeable percentage of one’s life to read it. The key to its effect lies in Hugo’s use of a sporadically omniscient narrator who reintroduces his characters at long intervals as if through the eyes of an ignorant observer — a narrator who can best be described as God masquerading as a law-abiding bourgeois….

The title itself is a moral test…. Originally, a miserable was simply a pauper (misere means ‘destitution’ as well as ‘misfortune’). Since the Revolution, and especially since the advent of Napoleon III, a miserable had become a ‘dreg’, a sore on the shining face of the Second Empire. The new sense would dictate a translation like Scum of the Earth. Hugo’s sense would dictate The Wretched.

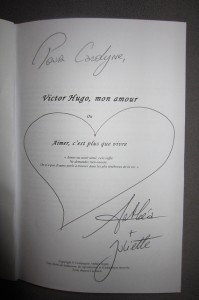

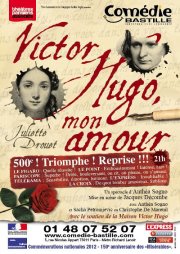

A podcast of “Les ‘Nouveaux Misérables’, 150 ans après” is here. And a popular play about Hugo’s longtime muse and mistress Juliet Drouet celebrates the year. On the play:

“All but ignored or forgotten in most official histories, Juliette exchanged with Victor 23,000 letters over their fifty-year love affair, letters which writer and actress Anthea Sogno has mined in order to write this exquisite and historically accurate play. Sogno herself gives a spellbinding and often very funny performance as Drouet.

“All but ignored or forgotten in most official histories, Juliette exchanged with Victor 23,000 letters over their fifty-year love affair, letters which writer and actress Anthea Sogno has mined in order to write this exquisite and historically accurate play. Sogno herself gives a spellbinding and often very funny performance as Drouet.

2012 is a significant year for Hugo enthusiasts, as it is the 150th anniversary of the publication of Les Miserables, a manuscript that might not have ever been published, had Juliette Drouet not taken care of it during one of Hugo’s several exiles. Sogno’s play, recognised as part of the national Hugo commemorations, and supported by the Maisons de Victor Hugo, has given over 500 performances in 130 French cities, to more than 70,000 viewers.”

The book made its imprint on me, but certainly I’m not alone. Robb writes:

One can see here the impact of Les Misérables on the Second Empire…. The State was trying to clear its name. The Emperor and Empress performed some public acts of charity and brought philanthropy back into fashion. There was a sudden surge of official interest in penal legislation, the industrial exploitation of women, the care of orphans, and the education of the poor. From his rock in the English Channel, Victor Hugo, who can more fairly be called ‘the French Dickens’ than Balzac, had set the parliamentary agenda for 1862.

(Oh, by the way, the immediate prompt for this post. The movie of the 1985 musical is slated for a Christmas release – with Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackman, Russell Crowe, Amanda Seyfried, and Sacha Baron Cohen & Helena Bonham Carter as les Thénardiers, and beloved Valjean veteran Colm Wilkinson as the Bishop. The first trailer was released yesterday, and is below. Looks dynamite, though like the book, this clip has been scathingly reviewed in some quarters.)