Guest Review: “Is Everything For Sale?”

Friday, July 30th, 2010 A first at the Book Haven: Elena Danielson reviews Debra Satz‘s Why Some Things Should Not Be For Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets (Oxford) — and she takes a Tolstoyan slant. In addition to being a whiz at Russian literature, Elena, Stanford archivist emerita and a former associate director of Hoover Institution, has been writing about the ethical dilemmas of archival practice for a quarter-century. She published the “Ethics of Access” in the American Archivist in 1989. In 2005, she won the Posner prize for an article in the American Archivist about access to East German political police files. In 2001, she also received the Laurel Award of the Polish Prime Minister for her work with the Polish State Archives. In 2004, she was named a Commander of the Order of Merit by the Romanian government for her work related to archival holdings in Romania.

A first at the Book Haven: Elena Danielson reviews Debra Satz‘s Why Some Things Should Not Be For Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets (Oxford) — and she takes a Tolstoyan slant. In addition to being a whiz at Russian literature, Elena, Stanford archivist emerita and a former associate director of Hoover Institution, has been writing about the ethical dilemmas of archival practice for a quarter-century. She published the “Ethics of Access” in the American Archivist in 1989. In 2005, she won the Posner prize for an article in the American Archivist about access to East German political police files. In 2001, she also received the Laurel Award of the Polish Prime Minister for her work with the Polish State Archives. In 2004, she was named a Commander of the Order of Merit by the Romanian government for her work related to archival holdings in Romania.

Is Everything for Sale?

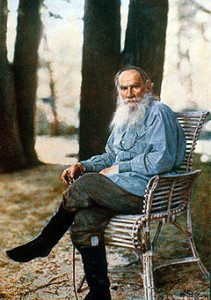

Debra Satz’s emphatic title could have come from one of Leo Tolstoy’s moralistic essays.

Why Some Things Should Not Be For Sale resonates with both sides of the political spectrum. Even MasterCard admits that some things are “price-less.” Pretty obvious: humans and human bodies should not be put up for sale or auctioned off.

Certainly the United States outlawed the market in human slaves by 1865 and Russia outlawed serfdom about the same time, in 1861. However, in the late 20th century, the libertarianism that sparked so much innovation and the globalization combined to produce some unintended consequences. Nearly everything has been swept onto the auction block. Satz reminds us that the clothes we are wearing were probably produced in a Third World country, and it’s likely that indentured, bonded or otherwise involuntary servitude, even child labor, helped produce the garment.

Immoral market mechanisms are not a new problem. Satz does not go into this long history, but it is the silent backdrop to her work. The issues she addresses have concerned some of history’s most thoughtful writers. Back in the 19th century, Lev Tolstoy was troubled by the legacy of serfdom that had enriched him and his family. Before the official emancipation of the serfs, he tried to liberate his own human holdings, but they were too suspicious or too savvy to take him up on the offer. Even after the Tsar liberated the bonded peasantry, Tolstoy continued to rail against the evils of private property and the ad hoc enslavement that goes with it.

Last winter at a Stanford “Ethics at Noon” brown bag talk, Satz analyzed the sale of body parts, especially the black market for human kidneys. Selling body parts is illegal, right? Well, in the United States human blood is certainly routinely bought and sold. Human eggs are purchased, often for large sums. This creates a “value forum.” A young woman attending Stanford may be able to command a higher price than a high school dropout. All the while the medical consequences for the seller are not yet clear. In Great Britain, such sales are illegal, the “donation” of body parts must be done altruistically without a purchase price. The sale of kidneys is still illegal in the United States, but the pressures are growing to create a legal market, just as there is for blood and human eggs.

As a social philosopher, Satz emphasizes the need to identify cases of “weak agency,” the vulnerable in society who will agree to almost anything for subsistence wages. As citizens with less clout, women often fall into the category of “weak agents,” forced into marketing sexual and reproductive labor.

The great Russian moralist was greatly disturbed by moves to detach sexual pleasure from the family-centered rituals of childbearing, making it a marketable commodity. The evils of prostitution in what we might call asymmetrical relationships are the subject of his highly moralistic, and nearly unreadable, last novel, Resurrection.

Satz points out cases of well-educated woman in the United States who have other options, but still sell their attractions to the highest bidder. Tolstoy also knew well that women of means could be caught up in this kind of marketing. The stunning and cunning character Hélène in War and Peace tells her husband she has no intention of having children. She takes up with powerful and wealthy men and then dies mysteriously at the hands of a French doctor after refusing to be treated by a good Russian doctor. The other great beauty in Tolstoy’s work, Anna Karenina, confidently tells her lover she has no intention of bearing any more of his children. She must also have had medical advice. In his essays, Tolstoy rants about the women and doctors who work against the will of Mother Nature. Modern medical technology has further detached desire from childbearing at each step in the process. Imagine what Tolstoy would think of the marketing of human eggs for substantial sums of money, and the use of surrogate mothers, who are often poorer women paid by wealthier couples.

The late 20th century era of great medical advances coincided with a time of great enthusiasm for the “invisible hand” of the marketplace as the best value forum for determining prices for just about anything. That naïve enthusiasm for deregulation has pretty much crashed, along with the market for hugely overvalued junk bonds, derivatives, and junk real estate loans. Satz points out that the same misplaced trust in financial markets crept into other areas of our American experience, and these need to be re-examined. As financial markets get re-regulated, other areas also need moral limits, some as legal measures and some as ethical standards.

The late 20th century era of great medical advances coincided with a time of great enthusiasm for the “invisible hand” of the marketplace as the best value forum for determining prices for just about anything. That naïve enthusiasm for deregulation has pretty much crashed, along with the market for hugely overvalued junk bonds, derivatives, and junk real estate loans. Satz points out that the same misplaced trust in financial markets crept into other areas of our American experience, and these need to be re-examined. As financial markets get re-regulated, other areas also need moral limits, some as legal measures and some as ethical standards.

Amazon has new copies for $16.47, used for $9.98, and a kindle version in between at $14.27. I paid list price of $35 at the Stanford bookstore so I could have a copy that had been autographed by the author. Tolstoy, who opposed private property, would have wanted me to check it out of the library. While her writing is much more accessible than his, if you have the time, read both. His work is in the public domain, as free e-text on Project Gutenberg. He’d like that.