Internet-speak and “truncated text” – is it OTT?

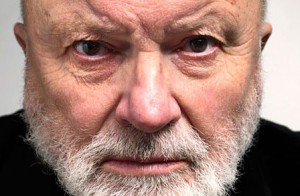

Saturday, March 31st, 2012I find myself agreeing with Geoffrey Hill, taking what I fear is an unfashionable stand against the popular British poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, when she said that that “the poem is a form of texting … it’s the original text”:

“It’s a perfecting of a feeling in language – it’s a way of saying more with less, just as texting is. We’ve got to realise that the Facebook generation is the future – and, oddly enough, poetry is the perfect form for them. It’s a kind of time capsule – it allows feelings and ideas to travel big distances in a very condensed form.”

Said the Hill, according to The Guardian:

“When the laureate speaks to the Guardian columnist to the tremendous potential for a vital new poetry to be drawn from the practice of texting she is policing her patch, and when I beg her with all due respect to her high office to consider that she might be wrong, I am policing mine,” said Hill … The Oxford professor of poetry has previously described difficult poems as “the most democratic because you are doing your audience the honour of supposing they are intelligent human beings”, saying that “so much of the popular poetry of today treats people as if they were fools”.

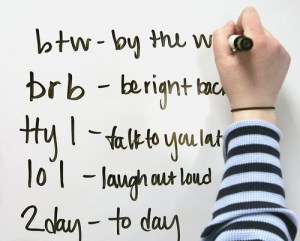

Speaking in Oxford, he said that he “would not agree that texting is a saying of more with less, and that it in this respect works as a poem”. “As the laureate says, poetry is condensed. Text is not condensed, it is truncated,” said Hill. “What is more it is normally an affectation of brevity; to express to as 2 and you as u intensifies nothing. Texting is like the old ticker tape: highly dramatic and intense if it’s reporting the Wall Street Crash or the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, not through any inherent virtue of the machine. Is the breaking news which runs at the foot of the screen on the BBC news channel condensed and consequently poetic? I fail to see how anyone could rationally claim that it is. Again texting is linear only. Poetry is lines in depth designed to be seen in relation or in deliberate disrelation to lines above and below.”

What, then, are we to do with the abbreviated, acronym-laced speech that is taking over today? For many of my younger Facebook friends, “lol” has become a verbal tick. On reading, it gives the impression that the speaker is giving way hearty laughter for each banal, and often distinctly unfunny, thought or announcement.

What, then, are we to do with the abbreviated, acronym-laced speech that is taking over today? For many of my younger Facebook friends, “lol” has become a verbal tick. On reading, it gives the impression that the speaker is giving way hearty laughter for each banal, and often distinctly unfunny, thought or announcement.

A beleaguered mother wrote this on her blog:

My daughter is always laughing at my ineptitude.

“GBH & K!” she yells to me, running out the door. (Great big hugs and kisses)

I stand there, looking mystified, as I try to figure out the latest abbreviation.

“Oh! H&K, too!” I shout. But she’s already out of sight.

My daughter is so good at KPC. (Keeping parents clueless) Just when I think I’ve got it she throws a new one at me.

KWIM was her favorite for a long time. And she’d pronounce it, like it was a word. “Kwim?” she’d ask. (Know what I mean?)

Or “ADK!” she’d roll her eyes, exasperated with her little brother putting on his shoes. (Any day now)

FWIW (that’s “for what it’s worth,” to the unitiated), here are the newest text-speaks from the great unwashed who gave us the now-shopworn LOL, OMG, and ROTFLMAO – brought to you by Vikram Johri over at Frank Wilson‘s Books Inq.:

FWIW (that’s “for what it’s worth,” to the unitiated), here are the newest text-speaks from the great unwashed who gave us the now-shopworn LOL, OMG, and ROTFLMAO – brought to you by Vikram Johri over at Frank Wilson‘s Books Inq.:

1. HST

2. OUAT

3. ISOT

4. IIMO… (this is followed by a question)

5. ITNEFY

6. TWW (Hint: sentence beginner when referencing the past)

7. OTW

8. WTFO

9. WOTS

10. FTLT

Can’t possibly guess what they mean? Flip down to the comments section, and I’ll give the answers. Meanwhile, it’ll be something to puzzle over on a slow Saturday.

Blogger Danish Dog added a few of his own:

1. HST Having said that

2. OUAT Once upon a time

3. ISOT In search of truth

4. IIMO Is it my opinion

5. ITNEFY If this never even finds you

6. TWW This was when

7. OTW Otherwise

8. WTFO What the fuck? Over.

9. WOTS Word on the street

10. FTLT For the last time