A Swedish award for a Swede? Ladbrokes has spoken…

Wednesday, September 29th, 2010Tomas Tranströmer is the odds-on favorite to win this year’s Nobel Prize for literature. Ladbrokes has spoken, putting his chances at 5 to 1. However, Bill Coyle at the Contemporary Poetry Review states the problem this way:

Every year, as the announcement of the Nobel Prize in Literature approaches, partisans of the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer hold a collective breath, hoping against hope. A win for their man is unlikely for a number of reasons. One is the residual fallout from 1974 when the Swedish Academy gave the prize to two of its own members, Harry Martinson and Eyvind Johnson. Both were fine writers, but the appearance of nepotism was impossible to avoid. No Swede—no Scandinavian—has won the prize since.

Reuters observes that “Poetry dominates the bookmakers’ list” and that “American writers set to be overlooked again” — unless, of course, you consider perennial American Nobel bridesmaid Joyce Carol Oates, ranked #12, or perennial groomsman Philip Roth, at #15. Thomas Pynchon is #16. Note that none of the Americans are poets. At least not primarily.

“Tomas Transtromer must surely be in pole position,” said David Williams of Ladbrokes. “He’s long been mentioned for the prize and we feel his work finally deserves this recognition.” Probably an indication he won’t get it. (You can read a few of his poems at The Owls website here.)

There’s an obscure Paraguayan playright — Nestor Amarilla — rumored to be shortlisted. No one’s ever heard of her, which would be in keeping with recent prizewinners. Do I sense another wicked Ted Gioia parody coming? Read his “Shocking Revelation: Nobel Lit Prize Has Been Picked by a Robot since 1994!“ (His slightly more sober “Nobel Prize in Literature from an Alternative Universe” here.

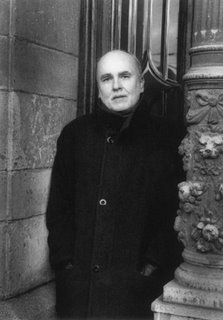

The man in the #2 favorite spot leaves me with divided feelings — it would be nice to see Polish poet Adam Zagajewski bag the prize — but the award has a way of turning lives upside down. (Read An Invisible Rope for some firsthand stories about what it did to Czesław Miłosz in 1980.) I remember Zagajewski kindly serving as my sherpa in literary Kraków — and, well, I’m selfish. Which is to say, I would miss his friendship.

I reviewed his book for the San Francisco Chronicle (and no, I didn’t write the headline) — I’m chuffed that it inspired Kay Ryan to write to the newspaper: “It was a thrill to read Cynthia Haven’s brilliant review the poet Adam Zagajewski’s book of essays, A Defense of Ardor, in this past Sunday’s Book Review. Almost never do I come across something about poetry that has the sting and bite of poetry in it. Zagajewski comes straight through Haven’s elegant and deeply informed prose. More of these brainy reviews please; more Cynthia Haven, please.” I hope they published it. I honestly can’t recall. Oscar Villalon sent it to me. God knows one gets enough slaps and punches.

I also profiled Adam for the Poetry Foundation magazine here - an article that still gets a lot of hits.

I remember meeting Adam for tea in Krakow’s main square, and being thrilled by the squadrons of pigeons. Adam assured me loftily that they were very stupid creatures. And, as a newcomer to his town, he showed me the Jagiellonian University, as the light was fading…

When I asked him about the future of poetry and poetry-lovers in the world of tweets and sound bites he said this (which didn’t make it into the final cut of the Poetry Foundation article): “We’ll be living in small ghettos, far from where celebrities dwell, and yet in every generation there will be a new delivery of minds that will love long and slow thoughts and books and poetry and music, so that these rather pleasant ghettos will never perish — and one day may even stir more excitement than we’re used to now.”

I keep this on my desk:

Only others save us,

even though solitude tastes like

opium. The others are not hell,

if you see them early, with their

foreheads pure, cleansed by dreams.- Adam Zagajewski, “In the Beauty Created by Others”