Hal Holbrooke, inevitably, as Mark Twain

I walked into the Piggott Theater only a few minutes late, but Hal Holbrook was already going at full gale force: “They interrupt each other!” he exploded. He was talking about the downfall of television news, and I had entered the tirade at mid-point. “Ninety percent of the American people don’t have an opinion worth putting on television!”

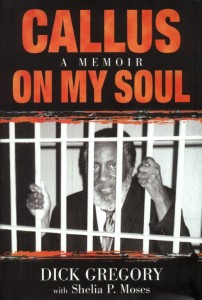

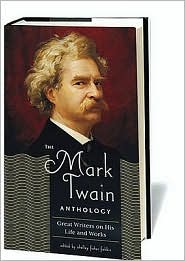

Even without the makeup, the famous white moustache, and the costume, Hal Holbrooke will always be Mark Twain. There’s nothing I know quite like it in the history of theater: Holbrook first performed his one-man show at the Lock Haven State Teachers College in Pennsylvania over half-a-century ago, in 1954 — and his most recent enactment of Mark Twain Tonight! took place Tuesday night in Memorial Auditorium. This was a follow-up session with Stanford students and a few hangers-on, like myself, at a Q&A session in Piggott Theater.

Holbrook is an astonishing 85 years old, and by now it’s impossible to know where Holbrook leaves off and Twain begins. It’s an miraculous meshing between the subject and his impersonator, between art and reality — to the benefit and ennoblement of both.

“The beauty of Mark Twain is that he lays a thought on your lap and walks away, and lets you handle it,” said Holbrook. So here are a few thoughts from Holbrook, or Twain, for you to handle:

On American leadership: “We take our opinions to the public trough, and follow the leader who makes the most noise.”

On Democrats and Republicans: He — or Twain? — disparaged the two-party system, which “turns voters into slaves and rabbits,” and praised the independent voter.

On the New York Times: “I know it leans to the liberal side, but so do I — so I have to watch out!” he said. Hence, he confessed that he listened to Glenn Beck — then, with his hand, put a mock pistol to his head and jokingly fired it. “It’s my job!” he said. “We’re not supposed to all think alike — but we are all supposed to listen to each other.”

On the intelligentsia: “I admire it, it’s important … but now that we’re done for,” he shrugged. “If the intelligentsia is not married to morality…” Then Holbrooke launched into a jeremiad about the downfall of America, which Twain (or Holbrook?) had compared a great machine whose belt has slipped, but still goes on.

On morality: While many blame homeowners for taking on mortgages they couldn’t afford, Holbrook said that people have always been suckers for things they can’t afford and morality enters with “your responsibility not to incite people to buy something they cannot afford” — an opinion that, taken alone and enacted into law, would cause major economic reform in America.

On performing villains: “You understand that people who are corrupt don’t get it — that’s the point. They don’t know they’re corrupt,” he said.

Holbrook keeps detailed accounts of all his Twain engagements — his last at Stanford was in 2000, and he was surprised when he checked his records and found his subject had been “Money is God.”

“You see, I was thinking ahead of the bubble!” he said. Looking around Silicon Valley, he felt “a lot that was happening here was chancy. What causes chanciness? Greed.”

“He wrote this! Great republics do not last.” Money causes corruption, which “excites dangerous ambitions and brings the republic down.”

Holbrook reminisced about playing another larger-than-life American from the 19th century, Abraham Lincoln. With corked shoes, Holbrook boosted his 6′ height a few inches to rival Lincoln’s 6′-3/4″ — but the size 14 shoes were beyond his reach. He urged young actors to do their research. In his own reading on Lincoln, he noted that contemporary news reports of Lincoln’s debates described his voice most frequently as “high,” “shrill,” “flat,” “nasal,” and “unpleasant.” A colleague described his speaking style: Lincoln planted his feet together, pointed forward, when he spoke, and didn’t move them while gesticulating wildly. It’s not, Holbrook said, the picture one forms from the statue in Washington D.C.

And it sounded like he was going to conclude with a hymn to thespians: “I think the acting profession is a noble profession. It’s been given a bad name by people who don’t know how to behave properly.”

“You have to believe in something beyond fame and money,” he said. “We are the clergymen of the world in disguise.”

When I left a few minutes early he was still talking — “like a waterfall,” as he warned.

Czesław Miłosz told me in 2000: “It seems to me every poet after death goes through a purgatory, so to say. … So he must go through that revision after death…”

Czesław Miłosz told me in 2000: “It seems to me every poet after death goes through a purgatory, so to say. … So he must go through that revision after death…”

We’ve written about the centenary of Mark Twain’s death this week

We’ve written about the centenary of Mark Twain’s death this week  Postscript: Hal Holbrook in

Postscript: Hal Holbrook in  Company of Authors

Company of Authors ontinuing through the afternoon at the

ontinuing through the afternoon at the

It’s Earth Day, and the

It’s Earth Day, and the

For most famous dead people, we celebrate the anniversary of births rather than deaths, unless they’ve been assassinated or canonized. This year, we’re making an exception for

For most famous dead people, we celebrate the anniversary of births rather than deaths, unless they’ve been assassinated or canonized. This year, we’re making an exception for

had, unwittingly, enriched our language of silence and our society’s lexicon of gestures. Literary language became more metaphoric and the language of gestures became textured with new layers. Glances, brow movements, intonations, body language became pregnant with new precise meanings and possibilities. The faces, the crowd, the gestures of Khomeini’s frenzied burial can, I think, only be understood in light of this new vocabulary.”

had, unwittingly, enriched our language of silence and our society’s lexicon of gestures. Literary language became more metaphoric and the language of gestures became textured with new layers. Glances, brow movements, intonations, body language became pregnant with new precise meanings and possibilities. The faces, the crowd, the gestures of Khomeini’s frenzied burial can, I think, only be understood in light of this new vocabulary.”

As I wrote elsewhere: ‘Imagine, for a moment, an American equivalent: a world where we were not allowed to speak of 9/11 and could not remember the victims in any public way. A world, moreover, in which our nation was ruled by the terrorists who did the killing. The comparison misses the enormity, still: Poland was a much smaller country with a prewar population of 30 million, and the number of those murdered 5-7 times as great as those who died in the World Trade Center.”

As I wrote elsewhere: ‘Imagine, for a moment, an American equivalent: a world where we were not allowed to speak of 9/11 and could not remember the victims in any public way. A world, moreover, in which our nation was ruled by the terrorists who did the killing. The comparison misses the enormity, still: Poland was a much smaller country with a prewar population of 30 million, and the number of those murdered 5-7 times as great as those who died in the World Trade Center.” replaced with an official monument “To the Polish soldiers—victims of Hitler’s fascism—resting in the soil of Katyń.”

replaced with an official monument “To the Polish soldiers—victims of Hitler’s fascism—resting in the soil of Katyń.”