Robert Conquest has had a distinguished career – and the honors aren’t ending for the British historian, who turned 92 in July. He’s already a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (as well as receiving the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in 1997), a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005. Then, on a sunny morning last August, he got one more feather.

In my work on the forthcoming An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz, I had noted that several of my contributors had received Order of Merit – including the NYC Polish poet Anna Fralich, the former diplomat John Foster Leich. So, curious about the honor, I accepted the invitation to see the Hoover Institution ceremony in which John Raisian, director of the Hoover Institution, and the writer Robert Conquest were to be lauded — though I had not read Conquest’s books about the murderous terror of life under totalitarianism.

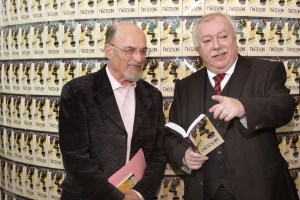

Conquest gets standing ovation (Photo courtesy Stanford Visual Arts)

Conquest was in delicate health, and did not stand to receive his award from Poland’s up-and-coming foreign minister, Radosław Sikorski. (Audio recording of the event available here.)

Sikorski and Conquest meet after the ceremony. (Photo courtesy Stanford Visual Arts)

In presenting the award, Sikorski said that as a Solidarność activist in his youth, Poles knew they were not alone, “because we had at least one great teacher”:

“At a very young age, Mr. Robert Conquest saw through that riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as Winston Churchill characterized the Soviets. And once he had understood it, he dedicated his life to revealing the diabolic logic hidden under the facade of propaganda and deception. His works, especially his monumental books, The Great Terror and The Harvest of Sorrow, brought to light a whole host of unimaginable tales of human suffering. He told the story that many did not want to hear, and stood for truth when it was not easy and fashionable. He gave a compelling testimony about the atrocities committed by the Soviets, which undermined the legitimacy of the Soviet rule and its ideology alike.

His books made a huge impact on the debate about the Soviet Union, both in the West and in the East. In the West, people had always had access to the information about Communism but were not always ready to believe in it. In the East, most of us did not harbor illusions about the utopian ideology under which we lived. We knew that the design - not only its execution - was flawed. Nevertheless, we longed for confirmation that the West knew what was going on behind the Iron Curtain. Robert Conquest’s books gave us such a conformation. They also transmitted a message of solidarity with the oppressed and gave us hope that the truth would prevail.”

Sikorski concluded by noting that Conquest was born in the year of Russia’s October Revolution: “he has outlived the Evil Empire and continues his mission of telling the true story about it.”

It’s not the only story he’s telling. A few weeks later in London, I was visiting with my publisher Philip Hoy of Waywiser/Between the Lines. As I was leaving, Phil handed me Waywiser’s newest book of poems: Penultimata. Phil advised me they were written by a nonagenarian, and that they are rather sexy.

The volume got quite a bit of praise: Clive James said “In poems about love, the subversive, lyrical proof that desire goes on into old age is alive in every  cadence and perception. As ever, he makes many a younger writer look short of energy.” My own editor at the Times Literary Supplement, poet Alan Jenkins wrote: “the whole of Penultimata is about what’s left of love and beauty, after a long life and 3,000 or more years of western civilization: to be recovered in memory, in a Roman figurine, in sharp sensuous delight, or in speculation on that nature of the universe.”

cadence and perception. As ever, he makes many a younger writer look short of energy.” My own editor at the Times Literary Supplement, poet Alan Jenkins wrote: “the whole of Penultimata is about what’s left of love and beauty, after a long life and 3,000 or more years of western civilization: to be recovered in memory, in a Roman figurine, in sharp sensuous delight, or in speculation on that nature of the universe.”

The sexy nonagenarian poet is Robert Conquest. Here are two of his offerings, chosen not for prurience, but for their wit.

The first is “Philosophy Department,” from a series called “All Things Considered”:

Such knotty problems! Check your lists:

How come the universe exists?

How does consciousness, free will,

Match up with brain cells? – Harder still:

Employing what we use for peeing

To penetrate another’s being,

And in her complementary hole

Surrendering one’s self, one’s soul.

Yes, the eternal paradox

Of hearts and minds and cunts and cocks.

That solved, it will be time enough

To tackle all the cosmic stuff.

Then there’s “This Be the Worse” — the poem, of course, is a take-off on friend and colleague Philip Larkin’s poem of the same name (find Larkin’s version here):

They fuck you up, the chaps you choose

To do your Letters and your Life.

They wait till all that’s left of you’s

A corpse in which to shove a knife.

How ghoulishly they grub among

Your years for stuff to shame and shock:

The times you didn’t hold your tongue,

The times you failed to curb your cock.

To each of those who’ve processed me

Into their scrap of fame or pelf:

You think in marks for decency

I’d lose to you? Don’t kid yourself.

cadence and perception. As ever, he makes many a younger writer look short of energy.” My own editor at the

cadence and perception. As ever, he makes many a younger writer look short of energy.” My own editor at the