The poet as a boy, 1898 (Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

The poet Marina Tsvetaeva said that fellow poet Boris Pasternak looked like “an Arab and his horse.”

He does, really. It’s an amazing, slightly Asiatic face.

I had ample opportunity to gaze at the visage of the Nobel laureate at the Ashmolean Museum, in the inconspicuous Print Room in a secluded corner on the second floor.

Not enough people know the author of Dr. Zhivago – for example, that he was primarily a poet, not novelist – but even fewer know the prominent members of his family. His father, Leonid Pasternak (1862-1945), was a brilliant painter and friend of the Tolstoys.

In the Print Room, the helpful librarians brought out a large portfolio of the artist’s chalk and watercolor sketches and paintings of his family, of the leading figures of his times, of still lifes and landscapes. With the white cotton gloves the museum provided, I lifted and examined each in turn, including portraits of Albert Einstein, Rainer Maria Rilke, and others.

I met the Pasternak family during the Pasternak celebration at Stanford last year (I wrote about it here). I was delighted to renew the acquaintance with two of them in Oxford – Ann Pasternak Slater and Catherine Oppenheimer, both nieces of the poet and granddaughters of the artist. Catherine is an eminent psychiatrist; Ann is professor emeritus of English literature at Oxford (she is currently writing about Evelyn Waugh).

Ann is also a formidable critic, and a matchless champion for Pasternak’s work. She wrote last year in The Guardian:

As a public speaker he was incomprehensible. His work is notoriously hard to translate. …

Pasternak’s work is also difficult because his mind-set is unpredictably complex, evocatively associative, synaesthetic and polysemous. His vocabulary is exceptionally wide, and his intellect has a pronounced metaphysical cast. In an uncollected letter to TS Eliot, Pasternak explores their shared aesthetic in ambitiously faulty English. Eliot’s art, he writes, like his own, is “a casually broken off fragment of the density of being itself; of the hylomorphic matter of existence . . .” Pasternak became much more accessible in his later work. Doctor Zhivago was suicidally vivid and forthright. The poems that accompany it are translucent.

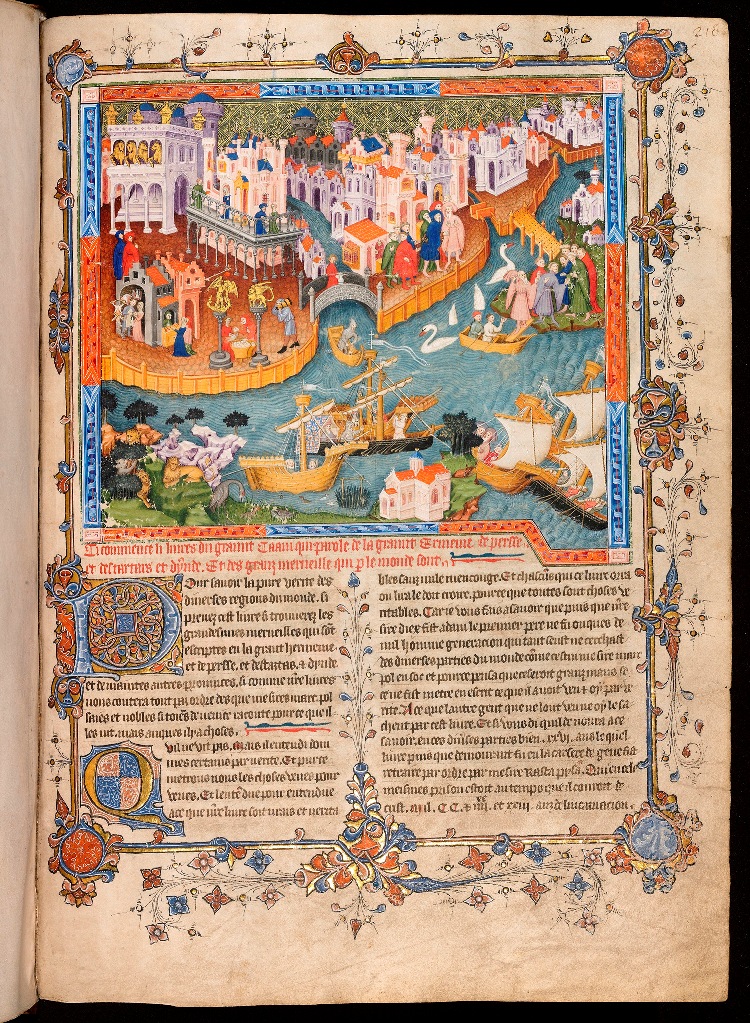

"The Yellow Tree: Autumn Landscape," 1918 (Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

From his schooldays, Pasternak tells us, Yury Zhivago had dreamed of writing “a book of impressions of life in which he would conceal, like sticks of dynamite, the most striking things he had so far seen”. Doctor Zhivago was that book. It was packed with dynamite and, as Pasternak expected, it blew up in his face.

I talk a little about that explosion here.

I had lunch with Ann and Catherine in the former’s Oxford home, which is almost a museum of their grandfather’s artwork. (A link for the Pasternak trust is here.) Of course we talked about the translations of the poet (Ann dissed the newest Pevear-Volokhonsky translation in the article I’ve quoted).

Ann describes her uncle’s poetry this way: “Boris’s poetry is formally rich, regularly rhymed, and metrically precise. It is full of delectable assonances, at once musical and wholly natural. My mother’s first priority was to reproduce his aural effects. She did. This difficult demand inevitably exacted its own price. Her English is flawed – it sounds Russian. But it sings, as Pasternak’s poetry does.”

My inevitable question: Which of the Pasternak translations does she favor? Her answer: Mother knows best. (The link, here, also has rare recordings of Pasternak reading his poems in Russian.)

Ann kindly gave me an out-of-print volume of her mother’s translations. Here’s an example of Lydia Pasternak Slater‘s translation:

Sultry Night

It drizzled, but not even grasses

Would bend within the bag of storm;

Dust only gulped its rain in pellets,

The iron roof – in powder form.

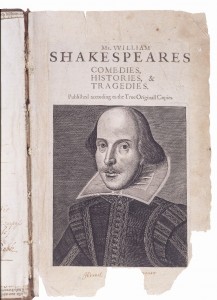

Rainer Maria Rilke, 1921-24 (Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

The village did not hope for healing.

Deep as a swoon the poppies yearned

Among the rye in inflammation,

And God in fever tossed and turned.

In all the sleepless, universal,

The damp and orphaned latitude,

The signs and moans, their posts deserting,

Fled with the whirlwind in pursuit.

Behind them ran blind slanting raindrops

Hard on their heels, and by the fence

The wind and dripping branches argued –

My heart stood still – at my expense.

I felt this dreadful garden chatter

Would last forever, since the street

Would also notice me, and mutter

With bushes, rain and window shutter.

No way to challenge my defeat –

They’d argue, talk me off my feet.

Buzzfeed is providing a useful service: Reviving little known punctuation marks, although I’m pretty sure the folks at Buzzfeed made some of them up out of their heads.

Buzzfeed is providing a useful service: Reviving little known punctuation marks, although I’m pretty sure the folks at Buzzfeed made some of them up out of their heads. The exclamation comma. As the site explains: “Just because you’re excited about something doesn’t mean you have to end the sentence.” I think I’m going to use that one a lot.

The exclamation comma. As the site explains: “Just because you’re excited about something doesn’t mean you have to end the sentence.” I think I’m going to use that one a lot. The third is very useful, and much more evocative than a parenthetical “snark” or the annoyingly ubiquitous “lol.” According to Buzzfeed: “Also called the Percontation Point and the Irony Mark, this one’s used to indicate that there’s another layer of meaning in a sentence. Usually a sarcastic or ironic one. So it is essentially a tool for smart people to use to make stupid people feel even stupider. Which makes it the best punctuation mark of all.”

The third is very useful, and much more evocative than a parenthetical “snark” or the annoyingly ubiquitous “lol.” According to Buzzfeed: “Also called the Percontation Point and the Irony Mark, this one’s used to indicate that there’s another layer of meaning in a sentence. Usually a sarcastic or ironic one. So it is essentially a tool for smart people to use to make stupid people feel even stupider. Which makes it the best punctuation mark of all.”