László Krasznahorkai: “So-called high literature”? Finito.

Saturday, July 7th, 2012

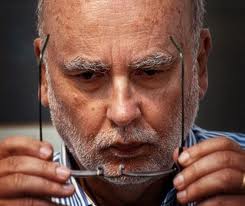

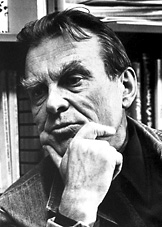

Hungarian writers tend to be a lonely lot – the fruit of their labor is stranded out on the most inaccessible branch of the broad language tree. Who speaks Hungarian, except those born to it? Its closest antecedents are Turkish and Finnish, and they aren’t all that close. Wisely, László Krasznahorkai divides his time between New York and Berlin, as well as the cosy little village of Pilisszentlászló, about half an hour out of Budapest. That, in addition to the skyrocketing reputation of his work, has put him in the world’s literary epicenter.

After all, Susan Sontag said he is “the contemporary Hungarian master of apocalypse who inspires comparison with Gogol and Melville.” W. G. Sebald said, “The universality of Krasznahorkai’s vision rivals that of Gogol’s Dead Souls and far surpasses all the lesser concerns of contemporary writing.”

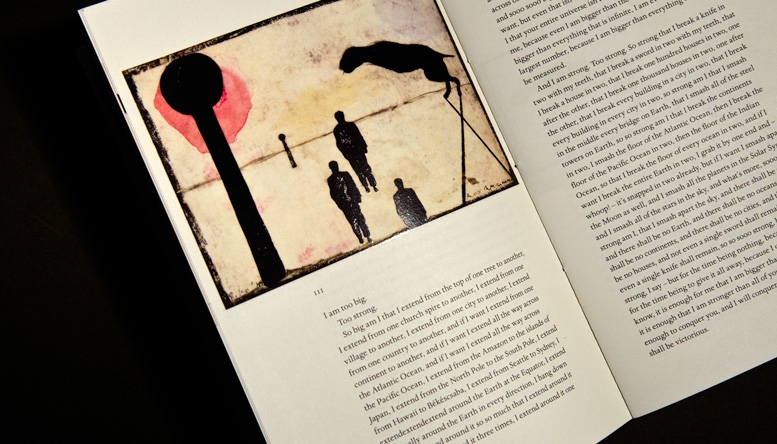

To my discredit, then, I discovered Krasznahorkai only this year when, in Paris, Daniel Medin shoved a Cahier into my hand. The short, 39-page work, Animalinside, was undertaken for the Cahiers Series as part of a collaboration with German painter Max Neumann (we’ve written about the Cahiers series here). For reasons to tedious to get into, the book wound up in a stack of backlogged reading, and I’d only got round to reading it after the interview in the current Quarterly Conversation.

The interview is republished from The Hungarian Review – a publication I regard with gratitude, as its editors allowed me to republish Czesław Miłosz‘s poem “Antigone,” translated by George Gömöri and Richard Berengarten – the poem, in English, exist only in the journal and An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz. It’s not the only reason I read the Q&A with interest, however; it’s lively stuff.

A few excerpts:

Ágnes Dömötör: Many people have the impression that your books are hard to read and to understand. That’s a myth, but don’t you think you’ve got some bad PR?

László Krasznahorkai: You know, the problem is that anything that’s the least bit serious gets bad PR. Kafka got bad PR, and so does the Bible. The Old Testament is a pretty hard text to read; anyone who finds my writing difficult must have trouble with the Bible, too. Our consumer culture aims at putting your mind to sleep, and you’re not even aware of it. It costs a lot of money to keep this singular procedure going, and there’s an insane global operation in place for that very purpose. This state of lost awareness creates the illusion of stability in a constantly changing world, suggesting at least a hypothetical security that doesn’t exist. I see the role of the tabloid press somewhat differently. I can’t just shrug it off and say to hell with it. The tabloid press is there for a serious reason, and that reason is both tragic and delicate.

AD: Suppose someone who has never read anything by you picks up this interview and says: what an interesting guy, which one of your books would you recommend to them? What would be a point of entry to your life’s work?

LK: The Old Testament. The Book of Revelation. Let them choose from my books at random.

AD: How do you relate to your fellow Hungarian writers? Do you ever e-mail one another? Would you tell György Spiró, for instance,‟I liked your last book, Gyuri?” I’m asking because in an earlier interview you seemed to see yourself as an outsider on the literary scene.

LK: I don’t just see myself as an outsider, I am one. Which doesn’t mean I’m not happy to see colleagues I admire; after all, we share the same fate. But I also worry about them. I worry, for instance, because they’re in literature, something that you can still sell for awhile, but it’s getting harder and harder. This kind of communication is really over and done with. Its disappearance is a rather obvious process; it is happening faster at some points of the world than at others. I’m afraid this kind of literature is not sustainable.

AD: You mean it’s not just the authority of literature that’s finished but literature as such?

LK: The so-called high literature will disappear. I don’t trust such partial hopes that there will always be islands where literature will be important and survive. I would love to be able to say such pathos-filled things, but I don’t think they’re true.

On our tabloids: “The structure of vulgarity is very complex.” He also talks about apocalypse, and “this rotten world we live in.” And rock bands? You can read about his favorite ones, along with the rest of the interview, here.

What does he think about bloggers, such as Humble Moi? “Recently one blogger suggested that I should be hanged. I immediately put on my space suit, started the engine and went to the moon for a while.” That puts me in my place.

Meanwhile, here’s what Irish novelist Colm Tóibín said about Animalinside:

Language for Krasznahorkai is a force struggling against the domination of cliché and easy consumption, offering small, well-organized revolts, plotting in upstairs rooms for plenitude and jagged rhythm, arming itself with clauses, sub-clauses and asides, preparing high-voltage assaults on the reader’s nervous system. … The world of his fiction is enclosed and stable, it must be taken on its own terms. … His work is full of menace, but it would be a mistake to read the menace either as political or as coming from nowhere. …