“I felt at home,” said Arthur Miller. Now his home will be ripped down.

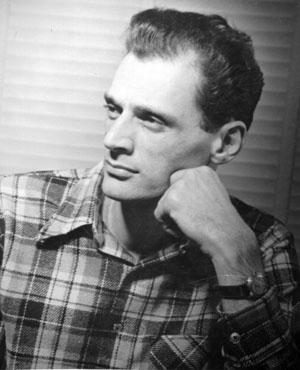

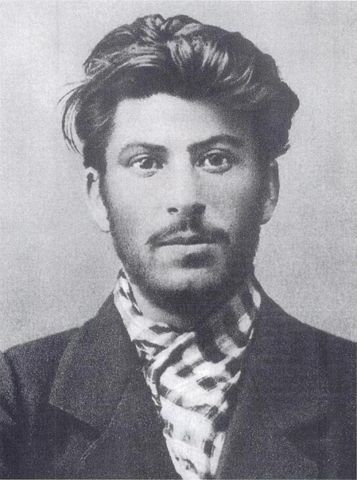

Thursday, September 20th, 2012Pulitzer prizewinning playwright Arthur Miller was born and reared in New York City – but he loved Ann Arbor, where he attended university. Go figure.

It would be swell if Ann Arbor returned the love, but it appears the city is about to tear down his digs at 439 South Division Street. The street holds memories for me – I lived at 701 South Division. For one academic year, I lived even closer to his ghost, around the corner on Thompson Street, somewhere in the 500 block.

So how did he wind up so far away from the endless pavements of Manhattan? “Miller’s father, a practical-minded businessman, was amazed to hear of a faraway school called Michigan that would actually pay students money for writing. His son told him about the prestigious Avery Hopwood Awards, built from a legacy given by another MIchigan alumnus who had made a fortune on Broadway with such slight bedroom farces as Getting Gertie’s Garter and Up in Mabel’s Room … Miller’s father was impressed, but he reminded his son that he had to make some money first – before trying his hand at the Hopwoods.” Elnora Nelson writes in Arthur Miller’s America: Theater and Culture in a Time of Change: “He arrived in Ann Arbor after a circuitous bus ride and a hitchhike, he said, quite simply, ‘I felt at home.”

From Ryan Stanton at AnnArbor.com:

A house where famous playwright Arthur Miller once lived when he attended the University of Michigan could be demolished if no one steps forward to buy it and relocate it.

That’s what U-M officials indicated at a neighborhood meeting Thursday night as they gave an update on the $29 million expansion of U-M’s Institute for Social Research building.

The 3,210-square-foot wooden house at 439 S. Division St. stands next to the ISR building, a block south of downtown Ann Arbor, and was Miller’s first residence when he attended U-M in 1934.

“I just think it should be known, before it is demolished, what it is,” said Ann Arbor resident Marilyn Bigelow, a self-described informal historian who showed up to Thursday’s meeting to let U-M officials know she’ll be fighting to preserve the house, which dates back to the late 1800s.

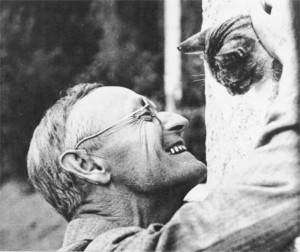

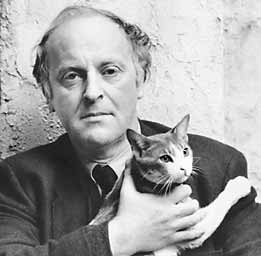

Of course the article includes photos: The homely wooden buildings of an earlier era, the soulless dark-glass facade of the Institute for Social Research, which needs ever more space, ever more parking. (The new $29 million expansion will have a “green roof,” of course.) The relics of Ann Arbor’s most eminent writers – Arthur Miller during the 1930s, Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky in the immediate years after his exile, briefly Robert Frost and W.H. Auden – don’t stand a chance. Not even a plaque to commemorate the building I must have walked past hundreds of times.

“Although most Miller studies trace the beginning of his literary career at Michigan to his undergraduate submissions to the Hopwood Awards Committee, he first made his mark in Ann Arbor as a writer for the Michigan Daily.” It was then, and is still, at 420 Maynard Street, a few convenient blocks away from our homes on South Division (and Thompson). I expect the 5-cent Cokes that formed the main of our diet in the 1970s were much the same as he had swallowed – and the hot-type presses were already pleasantly passé in my time. In my era, Tom Hayden had cut a greater swath in the Daily‘s consciousness – I remember Hayden on a return visit to the offices, to talk to the editors about Indochina. But Miller’s influence has proved the deeper and more lasting one. And we both got two Hopwoods in the end.

In his autobiography Timebends, Miller reflects much on the radical legacy of Ann Arbor and the Daily. But I liked this paragraph the best:

“In the thirties, one of Ann Arbor’s small-town charms for me was its reassuring contrast with dog-eat-dog New York, where a man could lie dying on Fifth Avenue in the middle of an afternoon and it would take a long time before anybody stopped to see what was the matter with him. A short ten or twenty years later people were looking back at the thirties nostalgically, as a time and caring and mutuality.”