Paul Celan, John Felstiner, and the soul of beauty

Sunday, October 21st, 2012 Some weeks ago, we discussed Simone Weil‘s comment that “distance is the soul of beauty.” At that time, Andrew Shields wrote to the Book Haven:

Some weeks ago, we discussed Simone Weil‘s comment that “distance is the soul of beauty.” At that time, Andrew Shields wrote to the Book Haven:

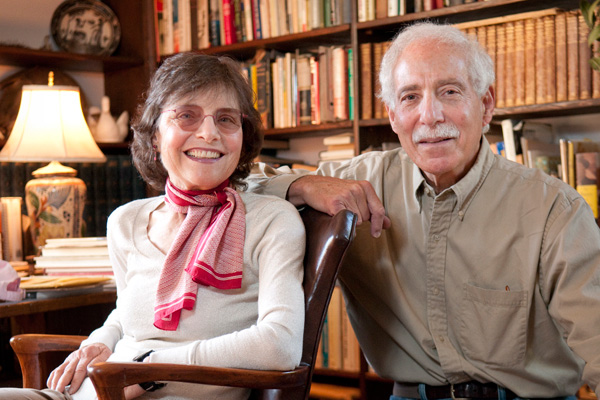

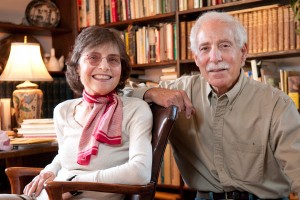

Back in the spring of 1988, several students and I (already graduated but still hanging around) spent several evenings at [author and translator] John Felstiner’s house, reading, translating, and discussing [Paul] Celan poems. The most memorable discussion was about “The Vintagers,” in which we discovered ourselves, as it were, as readers of the poem. Our experience of the poem (a “beautiful” experience) was connected to our distance from it, which we found characterized in the poem as the distance between those who make tears into wine and those who later drink it. That seemed like a figure of Celan the poet as wine-maker and ourselves as reader/drinkers.

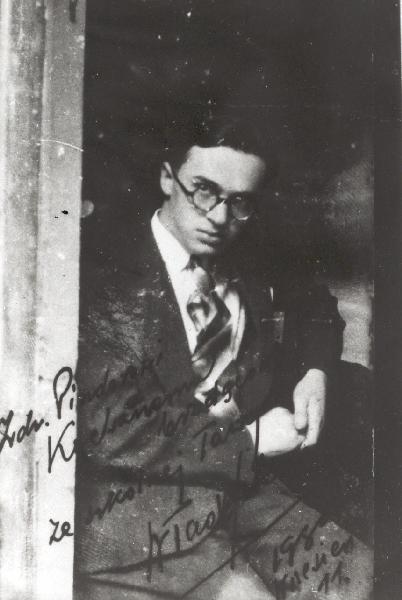

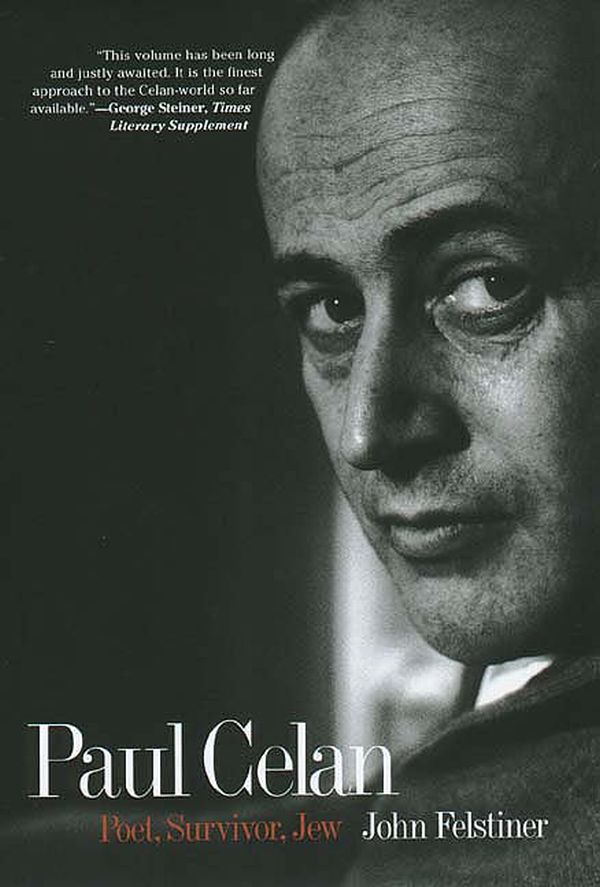

I wrote to John, asking if we could republish his translation of “Die Winzer” – so many know little of the German-language poet’s work besides his “Todesfuge.” In his 1995 literary biography, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew, John says the 1953 elegy “asks even more attentiveness than usual” in Celan’s oeuvre. The poem, he says, “ingrains autumn into itself: an elegy and at the same time a meditation on poetic process, impelled by rhythmic repetition.”

Here it is:

The Vintagers

They harvest the wine of their eyes,

they crush out all of the weeping, this also:

this willed by the night,

the night, which they’re leaning against, the wall,

thus forced by the stone,

the stone, over which their crook-stick speaks into

the silence of answers –

their crook-stick, which just once,

just once in fall,

when the year swells to death, swollen grapes,

which just once will speak right through muteness

down into the mineshaft of musings.

They harvest, they crush out the wine,

they press down on time like their eye,

they cellar the seepings, the weepings,

in a sun grave they make ready

with night-toughened hands:

so that a mouth might thirst for this, later –

a latemouth, like their own:

bent toward blindness and lamed –

a mouth to which the draught from the depth foams upward, meantime

heaven descends into waxen seas, and

far off, as a candle-end, glistens,

at last when the lip comes to moisten.

According to John, who is studying “creative resistance” during the Holocaust: “Despite this ever present ‘they’ in Celan, critics who are sure that ‘Die Winzer’ concerns the poetic process itself identify those who ‘harvest the wine of their eyes’ as poets taking on our pain and transforming it. Perhaps, but this disregards the people who first found voice in ‘Todesfuge,’ whose wartime suffering sifted through European earth. It’s they, a buried people, who are leaning against night in ‘Die Winzer,’ against the shooting wall, and who speak ‘into/the silence of answers.’ To say that ‘they’ are poets is off by a generation.”

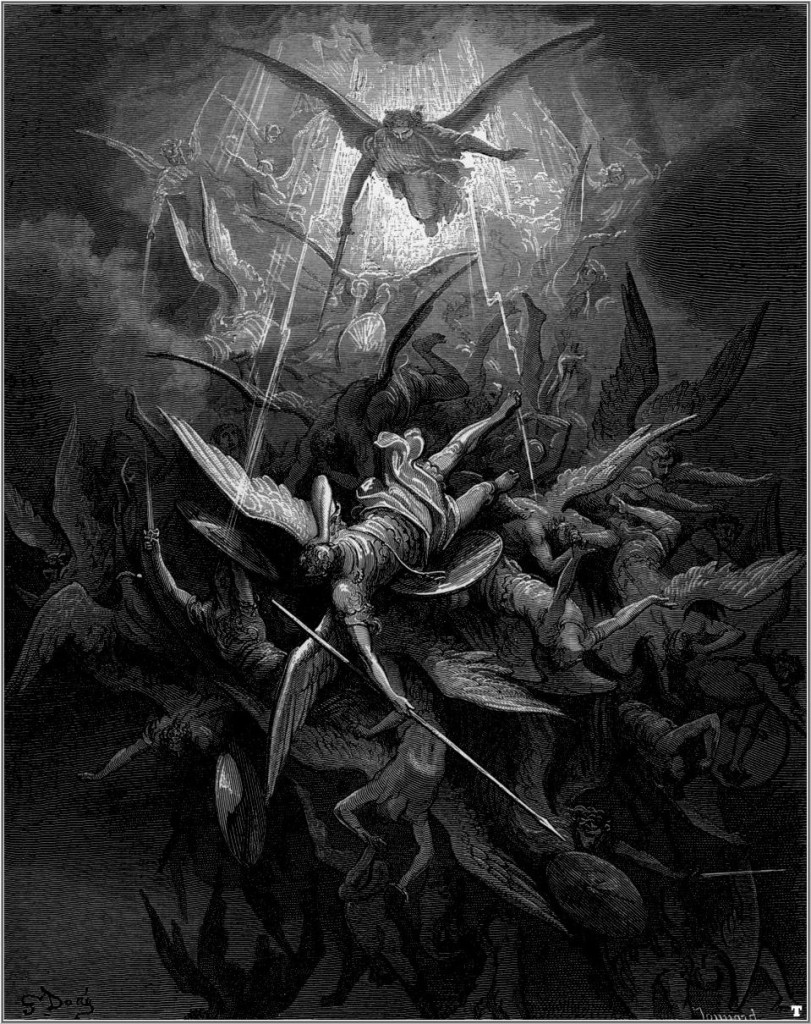

Noting that an earlier draft of the poem was called “Die Menschen” (roughly, “The Humans”), John writes (and these excerpts don’t nearly do justice to the Felstiner’s expert biography), “The change from ‘The Humans’ to ‘The Vintagers’ added a pastoral irony, since in German Romantic poetry the Winzer figures as a rejoicing worker. In Hölderlin, ‘The vintager’s brave joyous cry/Rings pure on sun-warmed vineyard slopes.’ Closer to Celan is Isaiah‘s prophecy: ‘upon thy harvest the battle shout is fallen. … And in the vineyards there shall be no singing … no treader shall tread out wine in the presses’ (16:9-10). Desolation threatens the harvest and the song alike. …

“And shortly before writing ‘The Vintagers,’ Celan had read Heidegger on Hölderlin’s 1801 elegy ‘Bread and Wine,’ in which Dionysus goes between humankind (die Menschen) and ‘they,’ the gods. Celan marked Heidegger’s phrase, ‘poet in a destitute time: singing on the trace of the departed gods.’

“The Vintagers” corresponds in a score of words to “Bread and Wine” and still refutes it. The later poet does not invoke gods or the mystery of water being turned into wine or wine into the blood of redemption. When, in Celan, ‘they cellar the seepings, the weepings,/in a sun grave they make ready/with night-toughened hands,’ we are to think not of Dionysus’s priests or Jesus’ disciples but of people forced to dig their own graves.”