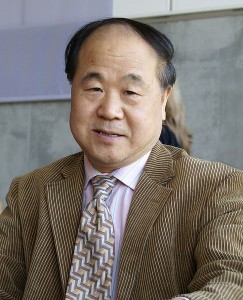

More on Mo: an “officially sanctioned artist” or merely a cautious kinda guy?

Friday, October 12th, 2012As may be gathered from yesterday’s post, I’d never heard of Mo Yan before yesterday’s award. While everyone today is laughing about the Onion satires that suggest that the Nobel peace prize has been awarded to the European Union (thank heavens it wasn’t the economics prize, as a friend noted), I’m still puzzling on Mo Yan, whose pen name is translated as “don’t speak.”

Here’s what Ted Gioia, whose weekly “Year of Magical Reading” spotlights the magical realism genre (it’s here), said this about him on my Facebook page: “Not a very inspired choice. If the Nobel judges wanted to turn to Asia, Murakami was the obvious candidate - and his work is more skilled, creative and influential than Mo Yan’s.

“He is presented as a brave critic of Chinese repression, but his works are actually quite cautious and seem self-censored to me. He aims for parody and humor, and is sometimes amusing, but I can’t see him as a Nobel laureate – unless the judges were determined to pick a Chinese author this year.”

Why not Bei Dao then … oh that’s right. They won’t do poetry two years in a row. Poetry must be kept in its place, after all.

David Ulin, my former editor at the Los Angeles Times Book Review has a piece in the L.A. Times today, spelling out what Ted had summarized:

Mo is what some critics deride as an officially sanctioned artist, a vice chairman of the China Writers’ Assn., celebrated by the establishment. Although he has been called “one of the most famous, oft-banned and widely pirated of all Chinese writers,” he recently was one of “100 writers and artists” who participated in a tribute to Mao Tse-tung. In 2009, he refused to sit on a panel at the Frankfurt Book Fair with dissident writers Dai Qing and Bei Ling, and he has avoided making any public statements about Liu [Xiaobo].

At the same time, his work has often hit on touchy subjects, such as the role of women in Chinese society and the Communist Party’s one-child rule. His 11th novel, Frog, published in 2009 and not yet available in the United States [we published an excerpt here – B.H.], involves a midwife confronted by the forced sterilizations and late-term abortions demanded by the party’s policy.

Mo’s detractors are forceful. “For him to win this award, it’s not a victory for literature; it is a victory for the Communist Party,” raged Yu Jui, a writer and democracy activist, in a blog post.

The article launches into something of a defense of new Nobelist, quoting his words in 2009: “A writer should express criticism and indignation at the dark side of society and the ugliness of human nature,” he said then, “but we should not use one uniform expression. Some may want to shout on the street, but we should tolerate those who hide in their rooms and use literature to voice their opinions.”

Meanwhile, John Freeman‘s interview with the Chinese author at the London Book Fair this week is included in Granta, which seems to be the go-to place for Mo Yan this month. The Q&A is here.

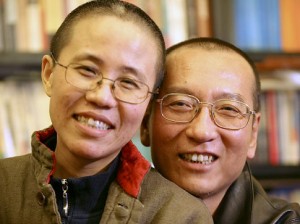

Am I the only one wondering today when they’re going to let their other recent Nobel writer (though a peace, not lit, prizewinner) – Liu Xiaobo – out of prison? He still has the distinction of being the second person ever to be denied the right to have a representative pick up his prize for him.