The young Sendler

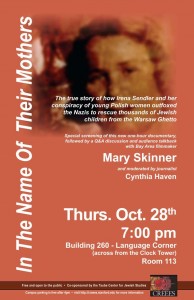

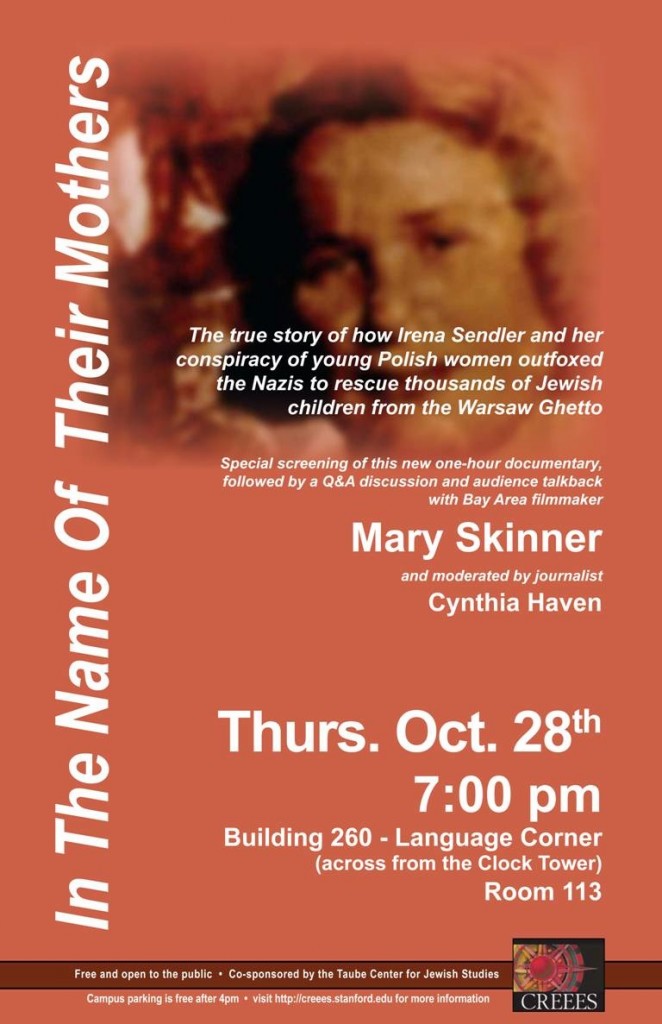

Finalement! The final installment of my interview with California filmmaker Mary Skinner, the mastermind behind In the Name of Their Mothers, which airs tonight on PBS (10 p.m. on KQED for Bay Area viewers – and the film shows tomorrow in Boston). The occasion is a perfect one: today, May 1st, is Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In the Name of Their Mothers is a documentary film about the Polish social worker Irena Sendler, who saved 2,500 Jewish babies and children from the Warsaw Ghetto and almost certain death at Treblinka. (Check local times here, and you can buy the DVD here.)

I’ve written about Irena Sendler before, here and here.

Skinner in Warsaw

This interview took place following a Stanford screening of the film on October 28, 2010. Part 1, with a trailer for the film, is here. Part 2, with a youtube video featuring an interview with Irena Sendler, is here. Part 3 is here.

For Part 4, the questions are all from the audience:

Q: From the start of this journey to the end of the film, what were the surprises for you?

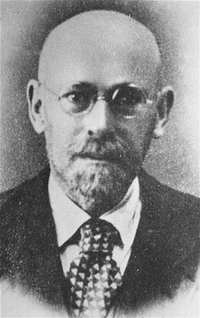

Man of Żegota: Władysław Bartoszewski

MS: Oh, that’s an interesting question. I started out thinking, “This is going to be a one-year project. One woman managed to smuggle 2,500 babies out of the ghetto, and I’m going to get that interview and it’s over.”

The shocking thing was how elaborate and how expansive this whole network of women was, and how complex. The matter of saving a child’s life was not so much getting them out of the Ghetto. The children could walk out of the Ghetto. It was it was feeding them and protecting them from the Germans and from blackmailers and getting the right paperwork for them. It was the whole bureaucratic nightmare that they had in a German-run social services department where they had to keep on reporting to the Germans. They also had to report what they were up to back to the government-in-exile.

Woman of Żegota: Magda Rusinek

So there was all this paperwork. Every time I was writing another proposal to try to raise money for this film I was thinking, Irena Sendler did it, I can do it.

That was a big part of it. The paperwork. It was all this doctoring and foraging and sending the papers and reporting and fighting to get more stipends and then hiding and then tricking this guy into telling the Germans. They had a lot of double-booking going on, and they all had to keep the code. The Germans had no idea, absolutely no idea what they were doing.

Q: There was a film made a few years back, The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler.

MS: I applaud the makers of that film for casting someone like Anna Paquin, who drew an audience to the film. I thought that the betrayal of the Ghetto was very good, very realistic, and the conflicts of this young social worker trying to convince mothers to part with their children. Obviously, I had gotten deeper into the story and so I knew that there were more elements to it that weren’t depicted in film, but I really applaud that film. I thought was it was quite authentic for a Hallmark movie, and I was really glad that 11 million watched it.

Hero in hiding: Adolf Berman

MS: I found it fascinating the way these women worked together, but there were some wonderful men who were part of this underground counsel to aid the Jews – people like Władysław Bartoszewski. Once again, Polish and Jewish resistance workers who were collaborating – people like Adolf Berman, who was who was living in hiding in Warsaw. He was responsible for identifying a lot of the parents who were willing to let their children go and putting them in touch with the network that could help them. There were some very brave, noble men that were part of this team as well.

Q: It’s still very hard to understand the brutality of the S.S. Where does it come from? Is it in some particular DNA strand?

MS: It’s not like Germans marched into Warsaw and said, “We’re here to annihilate the Jews.”

The first thing they did is they got rid of all the leadership in Warsaw and they said, “You know, these people are all our enemies. The mayor of Warsaw, the leadership within Warsaw, they were their enemies. So the people say, “Well, that’s war. Right.”

Magda honored by Yad Vashem ... and the boy she saved

Next, they start to say, “You know, the Jews have always wanted to govern themselves. We’re going to do them a favor. We’re going to let them all live in one place together and they can make their own rules. You just keep us apprised.” So the first couple of months of the Ghetto’s existence, they slowly moved people into one section of the city. Then they established the Jewish Council and the Jewish police force – they’re doing deals with the leadership of this group.

Jewish leaders were killed in early 1939 pogroms as well. They got rid of the Jewish leadership of the city. Some of them fled to the Soviet Union. So then, the public figured, “Well, they told us what they’re doing is they’re letting people be self-governing. It’s a separatist program. It’s apartheid. I guess we know and understand.”

Anna Paquin as Irena Sendler

Then the next thing we hear is that the people in the Ghetto are sick, and we’re going to do you a favor and not let you go into that area, because we don’t want you getting typhus. So then the population can’t see what’s happening behind the wall. And then you have the new external circumstances of less and less food as the German Army ran out of food.

So you ask, how could a Weimar soldier do this? Well, the Weimar soldier now has lost his buddies, he’s hungry, he’s been told these people are infested with typhus, and this is the only practical solution to this situation.

So then it starts to feel little bit like some contemporary things I’ve read about.

There were different types of people in the German army. There were people who were already brutal maniacs that were recruited for the S.S. and further trained to be brutal maniacs. Then there were simple German soldiers.

The way that Germans conducted themselves in Warsaw was they didn’t go into the Ghetto. For a long time, they ordered him Ukrainian conscripts to do a lot of the dirty work, they ordered Jewish police to do things, in exchange for supposedly … Everybody had to have a job, a livelihood. They told the people they deported, “We’re not deporting you, we’re giving you a loaf of bread and some margarine and jam and you’re going to a nice place to work, and you’re getting out of his ugly city.”

So even if the German soldiers, the simple Weimar soldiers, thought that that’s what was going on. You see how it gets more and more desperate.

It starts at the moment at which you objectify a human being. Which is to say, “That human being has no economic value and that human being does.” Then you’re in trouble. It proceeds from there. But it’s not like it started on Day One.

There were different kinds of German soldiers. And there were even some who helped Irena Sendler.

You can hear the entire October 28 interview with Mary Skinner – complete with slamming doors and the chiming of Stanford’s Bell Tower – here.

Yayyy for Mary Skinner! Her film about Irena Sendler, In the Name of Their Mothers, is an “official selection” at this year’s United Nations Association Film Festival (UNAFF).

Yayyy for Mary Skinner! Her film about Irena Sendler, In the Name of Their Mothers, is an “official selection” at this year’s United Nations Association Film Festival (UNAFF).