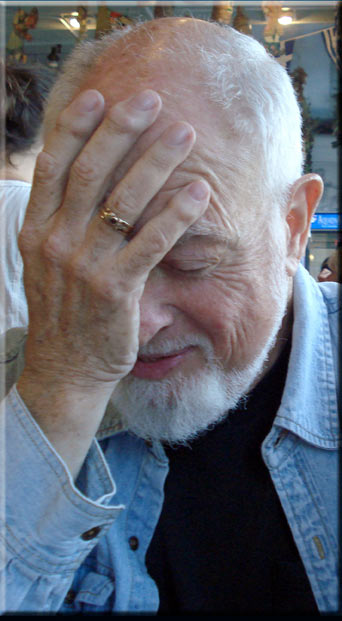

Jane Hirshfield, “the youngest and last of Czesław’s American poet-friends”

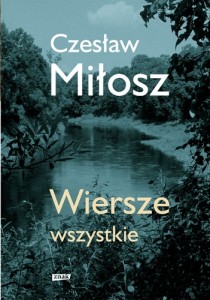

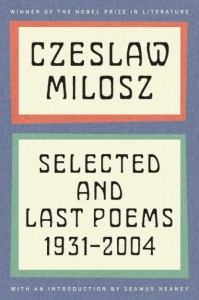

Sunday, October 14th, 2012 Some time ago, the Book Haven wrote about California poet Jane Hirshfield‘s appearance at Kepler’s (we’ve also written about her here). Jane and I came together over Czesław Miłosz a dozen years ago, when I interviewed her about her friendship with the Nobel poet for California Magazine. Two books and many articles later, after I have crossed the world tracing Miłosz’s journeys and speaking about him during Rok Miłosza, it was pleasing to find Jane’s elegant post about him on the Library of America blog “Reader’s Almanac” this week, as she remembers “Czesław Miłosz, (California) Poet.” (We’re also grateful to Jane and LOA for the mention of An Invisible Rope, in which Jane was one my contributors, and also for the hat tip to the Book Haven.)

Some time ago, the Book Haven wrote about California poet Jane Hirshfield‘s appearance at Kepler’s (we’ve also written about her here). Jane and I came together over Czesław Miłosz a dozen years ago, when I interviewed her about her friendship with the Nobel poet for California Magazine. Two books and many articles later, after I have crossed the world tracing Miłosz’s journeys and speaking about him during Rok Miłosza, it was pleasing to find Jane’s elegant post about him on the Library of America blog “Reader’s Almanac” this week, as she remembers “Czesław Miłosz, (California) Poet.” (We’re also grateful to Jane and LOA for the mention of An Invisible Rope, in which Jane was one my contributors, and also for the hat tip to the Book Haven.)

Here’s an excerpt from Jane’s piece:

In late 2002, at ninety-one and returned to Poland from his long self-exile (ten years in Paris, then forty as professor and poet in Berkeley), Miłosz wrote this small poem in his notebook:

I pray to my bedside god.

For He must have billions of ears.

And one ear He keeps always open to me.

(tr: Anthony Miłosz)

Reading this in English eight years after the poet’s death, I was struck by its curious “bedside.” A translator’s note explains: the original adjective means “near-at-hand,” “handy.” The Polish words for a first aid kit, a home-library reference book, and hand luggage all use some form of podręczny. This would, then, be not the distant and fearsome God of Judgment, but the rescuing one who knows every sparrow that falls, and the poem points toward a fully-felt fulcrum of balance: its god is local and large, intimate and immense, able to carry in a small, household form something vast, life-saving, and essential. Even the typography holds dual vision: the “g” of “god,” is lower-case; the pronoun is “He.”

All those years ago, when I first spoke to her on the phone, she told me how she had initially befriended the Polish poet. At a large outdoor gathering, the hostess approached Jane and suggested she introduce herself to Czesław Miłosz and his wife Carol. Everyone was intimidated by him, and so these gatherings could often be lonely affairs. Jane described it in An Invisible Rope: “I was, I believe, the youngest and the last of Czesław’s American poet-friends. I met him only after he had already turned seventy-five, when we were both invited to a group picnic on Angel Island, in the middle of San Francisco Bay. Not long after, he invited me to dinner after translating one of my poems into Polish. He showed me how largely it is possible for a person to live, even in old age, rapacious for knowledge, experience, and –though it is not a term he would use – the understanding of wisdom. His investigation of good and evil was not conceptual but personal and pressing.”

All those years ago, when I first spoke to her on the phone, she told me how she had initially befriended the Polish poet. At a large outdoor gathering, the hostess approached Jane and suggested she introduce herself to Czesław Miłosz and his wife Carol. Everyone was intimidated by him, and so these gatherings could often be lonely affairs. Jane described it in An Invisible Rope: “I was, I believe, the youngest and the last of Czesław’s American poet-friends. I met him only after he had already turned seventy-five, when we were both invited to a group picnic on Angel Island, in the middle of San Francisco Bay. Not long after, he invited me to dinner after translating one of my poems into Polish. He showed me how largely it is possible for a person to live, even in old age, rapacious for knowledge, experience, and –though it is not a term he would use – the understanding of wisdom. His investigation of good and evil was not conceptual but personal and pressing.”

And so her journey began – just as it began for me a dozen years ago, when I inadvertently became the last person in the U.S. to interview Miłosz (without warning, he returned to Kraków forever a few months after my California Magazine profile). Jane does her best to describe the impression, and does it much more eloquently than I can in this midnight blog post:

“Perhaps I am trying to sketch here a premise too complicated for such a brief form as this virtual Library bookshelf. But Miłosz, a poet of almost incalculable range, continually reminds us also that poems, and poets, live in the small, in the local and comic recognition, in the living and perishing real. We do not, cannot, live in general; even exile takes place in a place, a deck overlooking a Bay, on which a poet with extravagant eyebrows turns the pages of a New Yorker for its cartoons. We breathe the air that is near to us, scented with redwoods and lemons, or with the exhaust of refineries, power plants, airplanes, wars. If a poet in exile continues writing, he or she will be sustained by that air and that place, and will become of it.”

Then she cites the poem that I know is her favorite … or at least one of her favorites (can there ever really be a favorite?) She also reads and discusses the same poem, “Winter,” in the video below: