A tale of two cities: Newtown and Toulouse

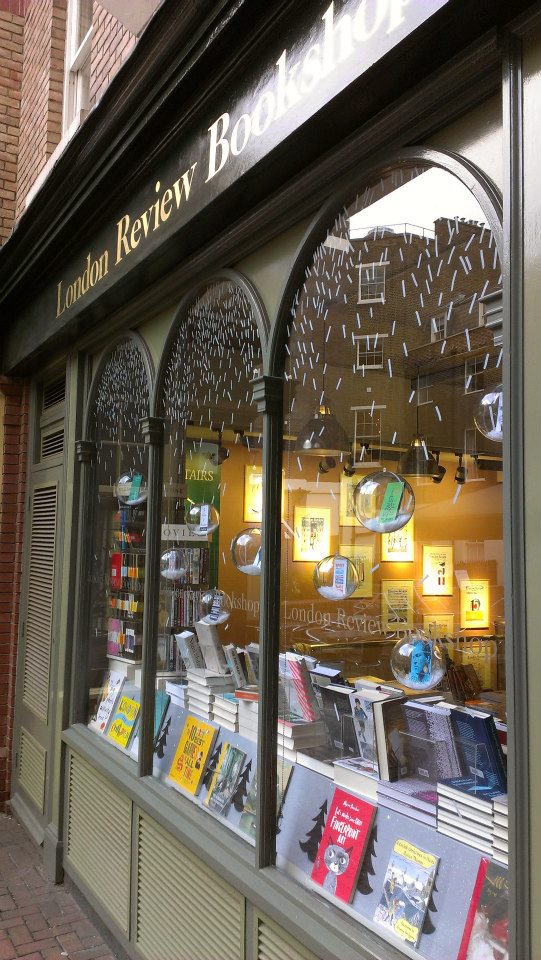

December 27th, 2012On my last night in the village of Lagrasse, my Calcutta companion and his two friends were all on their computers, trying to find a way for me to get to London more expeditiously than winding the long way back to Avignon, then Paris, then the chunnel to London with a combination of trains, cars, and taxis. We had almost given up when we found a cheap flight from Toulouse to Heathrow – saving me a little money and a lot of time.

It was a city I was barely aware of. So it is strange to have it come to my notice twice today, a few weeks since my brief visit there. First occasion: I read Janet Lewis‘s The Wife of Martin Guerre, in which that ancient city plays a pivotal role. Second occasion: Cécile Alduy tweeted me about her New Yorker article today, “Two Schools: Newtown and Toulouse.”

She wrote:

In France, where I was visiting my family for an early-winter break with my four-year-old daughter, the reaction to the Newtown school shooting was one of horror and of bewilderment—“Incomprehensible,” “unbelievable,” “unthinkable,” or, more often, dingue(crazy). Disbelief altered the faces of Parisians usually known for their urban cool. In spite of the biting cold and urgent plans for Christmas shopping, they could be seen, haggard, reading the headlines in the green kiosks of the street newsstands over and over again, or staring at the news channel in cafés that normally cater to soccer fans. When they learned that I’ve lived in California for close to ten years, they’d ask me, “Why? Why?” … The answer, that the American Constitution appears to guarantee a right to bear arms and that no politician is ready to take on the National Rifle Association and other pro-gun lobbies, was met by an uneasy silence. And then this, whispered, looking away: “How can you put your daughter in a preschool in San Francisco and sleep at night?”

Yet, she points out, “French schools are not immune from deadly madness.” Last March, “Mohamed Merah, a self-proclaimed jihadist on an American no-fly list, erupted at the Ozar Hatora Jewish School in Toulouse at 8 A.M., a camera affixed to his belt, and started to fire indiscriminately at the playground with an automatic pistol.”

She compares the two cities, the two nations, and their attitudes and their laws regarding guns and violence. Read the rest of it here. Merah, she said, is a terrorist “in the legal sense of the term,” she writes. But Adam Lanza? He, too, spread terror, “though the meaning of his action will remain forever sealed.” As someone said to me, perhaps it has no meaning, and in a nihilistic age, that is its meaning.

Like every other issue in this country, gun control in the wake of the massacre quickly became a polarized tit-for-tat, with blame, snark, threats, grandstanding, and name-calling, all resulting in skyrocketing gun sales.

There was a moment when everyone, even the NRA, realized that something had to be done. I hope that moment hasn’t passed, because I don’t think this is the sort of issue that can be resolved by one side running over the other and shoving something down the opposition’s throat (Cory Booker on the “false debate” here). We’ll need everyone onboard, together, to address this as a nation.