Medical anthropology

Medical anthropology is the study of how health and illness are shaped, experienced, and understood in light of global, historical, and political forces. It is one of the most exciting subfields of anthropology and has increasingly clear relevance for students and professionals interested in the complexity of disease states, diagnostic categories, and what comes to count as pathology or health.

Medical anthropology is the study of how health and illness are shaped, experienced, and understood in light of global, historical, and political forces. It is one of the most exciting subfields of anthropology and has increasingly clear relevance for students and professionals interested in the complexity of disease states, diagnostic categories, and what comes to count as pathology or health.

At Stanford some of our principal areas of inquiry include cultures of medicine, the social nature of emergent biotechnology, the economics of bodily injury, psychic expressions of disorder, the formation of social networks on health, the lived consequences of disability and inequality, and ever-changing concepts of human biological difference and race. Several of our core faculty research these issues in increasingly important geographical areas in the world today. These include Africa, Asia, and Latin America in addition to the United States and its borderlands. We engage with patients, health scientists, and larger publics at home and abroad in order to contribute to a more robust understanding of the coproduction of disease and phenomena like poverty, social status, global standing, racism, and nationalism. Our program seeks students who creatively imagine interdisciplinary approaches to health questions, wish to increase dialogue with medical professionals, and aim to rethink operative principles within science and medicine.

Our core group of faculty includes:

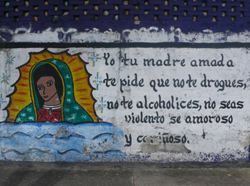

Angela Garcia: Professor Garcia’s work explores political, economic and psychic processes through which illness and suffering is produced and lived. Through long-term ethnographic research with poor families and communities struggling with multigenerational experiences of addiction, depression, and incarceration, she draws attention to emerging forms of care and kinship, accounts of cultural history and subjectivities, and relations of affect and intimacy, that are essential to understanding health and life. Working in the United States and Mexico, her work also demonstrates the urgent need for drug law reform and new approaches to ethics and therapeutics as they concern suffering in shared and transgressive formations.

Angela Garcia: Professor Garcia’s work explores political, economic and psychic processes through which illness and suffering is produced and lived. Through long-term ethnographic research with poor families and communities struggling with multigenerational experiences of addiction, depression, and incarceration, she draws attention to emerging forms of care and kinship, accounts of cultural history and subjectivities, and relations of affect and intimacy, that are essential to understanding health and life. Working in the United States and Mexico, her work also demonstrates the urgent need for drug law reform and new approaches to ethics and therapeutics as they concern suffering in shared and transgressive formations.

Duana Fullwiley: Professor Fullwiley explores how global and historical notions of health, disease, race, and power yield biological consequences that bear on scientific definitions of human difference. Through an ethnographic engagement with geneticists and the populations they study, she underscores the importance of expanding the conceptual terrain of genetic causation to include poverty and on-going racial stratification. She explicitly writes in the long histories of inequality and dispossession suffered by global minorities that often go missing from medical narratives of genetic disease and ideas of “population-based” severity. Working in France, West Africa and the United States, she details the legacy effects of postcolonial, post-Reconstruction, and Progressive Era science policies on present-day health outcomes. She also chronicles the remnants of racial thinking in new population genetic research and works with scientists to redress them.

Lochlann Jain: Professor Jain's research is primarily concerned with the ways in which stories get told about injuries, how they are thought to be caused, and how that matters. Figuring out the political and social significance of these stories has led to the study of law, product design, medical error, and histories of engineering, regulation, corporations, and advertising.

Jamie Jones: Professor Jones is a biological anthropologist with general interests in human ecology and population biology. Within this broad category, he is primarily interested in three areas: biodemography; disease ecology; and the evolution of human life histories.

Matthew Kohrman: Professor Kohrman’s work explores the ways health, culture, and politics are interrelated. He focuses on the People's Republic of China. He has written about disability, the emergence of a state-sponsored disability-advocacy organization and the lives of Chinese men who have trouble walking. He is now working on tobacco addiction and the state.

Tanya Luhrmann: Professor Luhrmann is interested in the way the non-material becomes real for people. This leads her into the study of psychiatric illness (psychosis in particular) and the supernatural and spirituality, and the way that different theories of mind may affect even someone’s sensory experience in pathology and health.

What sets this program apart?

An engaged orientation

Our group at Stanford believes that anthropological analysis is not just for anthropologists and not just for the classroom. It matters elsewhere. Whether it is cancer, psychiatric disease, drug addiction, injury and disability, racialized health disparities, genetic disorders or the leading cause of premature death, tobacco, we tackle issues of great importance for people the world over. In addressing the societal and bodily aspects of these problems, we encourage our students to work with affected communities, medical professionals, basic scientists, patient advocates, and health NGOs while aiming to reach even larger publics.

The goal of our work is to advance the field of anthropology, which is the disciplinary home of medical anthropology, but to do so in ways that also advance thinking within broader intellectual communities. The field of medical anthropology addresses afflictions of increasing importance that are seldom sufficiently understood by biomedicine alone. Much of our work focuses on how health problems arise from larger social issues, which must also be addressed. As we strive to dissolve the stark divides between the life and the social sciences, we work in the spirit that cross-disciplinary conversations are possible and necessary to achieve effective medicine, humane healing, and ethical science. In this vein, we encourage our students to publish in the flagship journals of anthropology as well as in relevant health science and more popular mainstream venues.

Theory and Methods

We are steadfast in our commitment to ethnography, affirming its empirical merits and value for theory building. We also realize that some research questions benefit from other methods, including statistical reporting, demographic observations, and survey techniques. In its specifics, training in our program includes courses in anthropological theory, the anthropology of science and technology, psychiatric anthropology, and various area foci where specific health problems are more prevalent for geo-political reasons. We expose students to these diverse approaches to allow them to contribute innovatively to anthropology as well as to a broader set of audiences. To facilitate this work, we also collaborate with Stanford’s Center for Comparative Studies on Race and Ethnicity (CCSRE), the Center for International Studies (FSI), the Department of Medicine, the Department of Psychology, and the program on Science and Technology Studies (STS).