Humanities at Stanford

Inside the humanities at Stanford University

Getting to the ‘Heart’ of the Matter

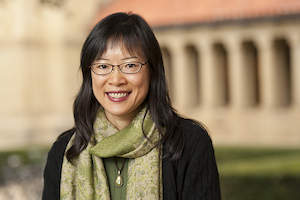

Stanford professor Haiyan Lee chronicles the Chinese “love revolution” though a study of cultural changes influenced by Western ideals.

This is a love story: A young Chinese man, Bohe, and a young Chinese woman, Dihua, have just been betrothed. Both of them are amenable to the parentally arranged match. Unfortunately, before they have the chance to marry, the Boxer Rebellion of 1898 erupts and Bohe is separated from Dihua. By the time she is reunited with him in Shanghai, he has become an opium addict. Dihua, a virtuous Confucian woman, tries unsuccessfully to save him and, after he dies, commits the remainder of her life to monastic celibacy.

This is a love story: A young Chinese man, Bohe, and a young Chinese woman, Dihua, have just been betrothed. Both of them are amenable to the parentally arranged match. Unfortunately, before they have the chance to marry, the Boxer Rebellion of 1898 erupts and Bohe is separated from Dihua. By the time she is reunited with him in Shanghai, he has become an opium addict. Dihua, a virtuous Confucian woman, tries unsuccessfully to save him and, after he dies, commits the remainder of her life to monastic celibacy.

The relationship in The Sea of Regret, written in 1906 by Chinese author Wu Jianren, might not fit modern definitions of romantic love. Yet in early 20th-century China, where passion was defined as devotion to Confucian standards shown through one’s daily demeanor, Dihua’s example of valiant self-sacrifice was the epitome of passionate fulfillment.

This is just one of the examples from nineteenth century Chinese culture that help to paint a picture of a society on the cusp of change and grappling with the onslaught of Western ideas, particularly those that associated romantic love with modern freedom and individuality.

Haiyan Lee, an associate professor in Stanford’s Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, has been studying Chinese literature and culture from the pivotal period between 1900 and 1950 with the aim of documenting what she calls the “sentimental revolution” of China.

Euro-American culture introduces ideas about love, freedom, and individuality

Overall, Lee characterizes the history of love in China as “a tortuous process of negotiation and hybridization, which is still very much ongoing,” yet notes that one of the effects of globalization on modern life has been the localization of European Enlightenment ideas about love, freedom, and individuality. Thanks to the enormous impact of Euro-American culture, particularly via Hollywood movies, “Contemporary Chinese understandings of love and sexuality are increasingly converging with the dominant western paradigm.”

In other words, as Professor Lee states, globalization has entailed the embracing of “basic western-derived, sentiment-based assumptions about personhood and sociality,” which she said, “has paved the path for melodramatic love stories like Titanic to conquer China and much of the rest of the world.”

In other words, as Professor Lee states, globalization has entailed the embracing of “basic western-derived, sentiment-based assumptions about personhood and sociality,” which she said, “has paved the path for melodramatic love stories like Titanic to conquer China and much of the rest of the world.”

Winner of the Association for Asian Studies Joseph Levenson Book Prize in 2009 for the best English-language academic book on post-1900 China, Lee’s Revolution of the Heart: A Genealogy of Love in China, 1900-1950 (Stanford University Press, 2007) chronicles the structures of feeling throughout modern Chinese history. In her research, Lee develops a genealogy of Chinese notions about love (qing) through an examination of a wide range of texts, including literary, historical, philosophical, sociological, and popular cultural genres. As Professor Lee explains, “[these] ideas of love and emotion tell us a great deal about a culture and society, since when we talk about love, we are also talking about a host of other things.”

Unconventional study of emotions reveals origins of cultural change

The story of Bohe and Dihua, for example, is at one level a universal tragic love story about a star-crossed couple. But at another level, it is also about the virtue of constancy, exemplified by the female protagonist Dihua. Against the backdrop of rebellion, social upheaval, and dislocation, Dihua remains constant to her ailing mother and her wayward  fiancé. Even after both are dead and gone, she honors their memory by suspending her own life in pious contemplation. Such an extravagant gesture of devotion is likely quite alien to today’s readers, Chinese as well as American.

fiancé. Even after both are dead and gone, she honors their memory by suspending her own life in pious contemplation. Such an extravagant gesture of devotion is likely quite alien to today’s readers, Chinese as well as American.

Inspired by an English literature course on Victorian fiction that she took during her doctoral studies, Lee began to consider issues of love and sympathy in the Chinese context. The academic study of emotion in literature and history was relatively novel in the 1990s. Lee said it has since caught on and blossomed into a robust subfield in the last decade, making Lee’s on-going bibliography longer by the month.

Spanning the evolving spectrum of affective expressions in China, professor Lee’s research methodology is somewhat unconventional. In

stead of constructing arguments around specific authors or genres in literature, she turns her lens to what is perceived as “common sense” in Chinese culture. It is through this genealogical excavation, done across literary and non-literary materials that she can identify the process by which cultural norms today took shape over the course of China’s modern century.

Lee says what she enjoys most about her approach is how it surprises people that “what they take for granted and have internalized as a cultural instinct has a much more recent origin than they might expect.”

Lee takes a similar exploration approach in her upcoming publication, The Stranger and the Chinese Moral Imagination, a work that focuses on contemporary China and issues of morality as refracted through engagement with strangers. In particular, Lee notes how “socialist China marks certain classes of people as enemies of the state and regards them as strangers, outsiders, and pariahs.”

By Camille Brown