SAGE

To Bean or Not to Bean, Soy is the Question: Essential Answer

By Judee Burr

I have heard that the production of soy is actually quite bad from a sustainability point of view. As a vegetarian, what are my best options in terms of soy products (if indeed there are good options), or if not soy products, what are other good alternatives that provide the protein that soy doess?

Asked by Marc Evans, ’10, MA ’11, Stanford, Calif.

As a strict vegetarian, I know how easy it is to fall into the trap of eating copious amounts of soy. I spend so much time explaining my choice not to eat meat that I sometimes forget to think closely about what I am putting in my body. You’re right though, there are serious issues with the way some soy is grown. The short answer is that eating soy is almost always more environmentally friendly than eating meat. But there are still good reasons to pause before making tofu your only source of protein and patting yourself on the back for being green.

Soy is a complicated little bean. In an individual’s diet, it can be a healthy source of protein and fiber. But as a global commodity crop, it can leave a devastating environmental footprint. I took my questions about soy production to Professor Rosamond Naylor, director of Stanford’s Center for Food Security and the Environment. She told me that problems with soy come from relatively recent changes in how and where it is grown. We’re not just talking about hoards of vegans who want their soymilk: Today, most of the 260 million ton global soy crop is fed to animals or converted into biofuels. Today, more than 90 percent of the soy grown in the United States has been genetically modified, primarily to stand up to common herbicides. And as the crop has become increasingly valuable on global markets, vast areas of tropical forest and savannah, especially in Brazil, have been clearcut to make way for horizon-spanning plantations.

In 2011, genetically modified (GM) soy was the leading genetically modified crop globally – occupying some 185 million acres of land area, or nearly twice the land area of California. GM crops make it easier for farmers to produce an abundant harvest. The problem is that extensive GM crop use is actually an environmentally dangerous practice. When farmers’ fields are home to only a single crop, farmers are much more susceptible to disastrous crop failure—if a pathogen infected the soy, the entire crop would be gone. Creating strains of soy that are resistant to herbicides can also cause farmers to use more of those herbicides to combat weeds that develop an herbicide resistance. Residues from these chemicals can remain on the plants and have been linked to severe health problems for farm workers, and potentially for consumers. GM crops also make farmers dependent on the agricultural biotechnology companies that synthesize their seeds. Unfortunately, the world’s largest producers of soy—the United States, Brazil and Argentina—rely heavily on GM soybeans. Check out the Nitty Gritty answer for more on the environmental and health impacts of GM soy.

Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest and Brazilian savannah (or cerrado) is an equally disturbing problem driven by soy production. The United States and Brazil are fighting for the lead in the global market for soy, and Brazil has relied on cropland expansion to increase their production levels.

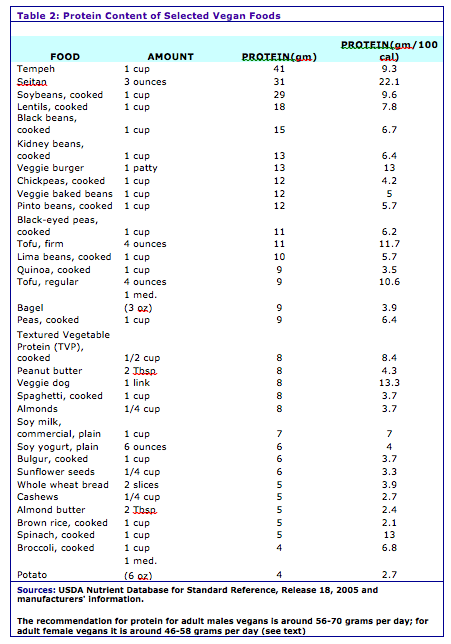

What happens after soy reaches our mouths? Soy is a great source of vegetarian protein, but it’s not the only one. Vegetarians who do not eat soy or are avoiding the wrong kinds of soy can get the necessary protein from other sources. According to the USDA Dietary Reference Intakes, adults should eat about 0.36 grams of protein per pound of weight, every day. For a 140-pound person, that means 50.4 grams of protein per day, or a little less than 2 ounces of pure protein. Eggs can be a good source of protein for non-vegan vegetarians – one egg contains about 6 grams of protein. Egg-eaters can be environmentally conscious by buying free range, organic (no antibiotics, fed with organic feeds) eggs. But there are also plenty of soy-free, vegan food alternatives that provide even greater amounts of protein. The chart below lists many of these delicious alternatives, such as the meat substitute seitan, made from congealed wheat gluten, and many protein-rich grains and beans. Tempeh and textured vegetable protein are soy products.

We should consider the place of soy in our diets the same way we consider everything else that we eat – by understanding where our food comes from and the impact it has on our health. Can you eat sustainable soy? Yes. Are there vegetarian substitutes for soy that will give you the right amount of protein? Absolutely. Are there any foods that will always be sustainable, no matter where they are grown? No, probably not, because food is necessarily linked to the way it is grown, harvested, and shipped. So keep thinking and keep eating.

JUDEE BURR, '12, is a double major in earth systems and philosophy.

Actions

Related Links

-

Indomitable

November/December 2008 -

Let Me Introduce Myself

September/October 2008 -

The Effort Effect

March/April 2007 -

Seeing at the Speed of Sound

March/April 2013 -

Changing His Pitch

May/June 2013

Comments (2)

Ouch! So much misinformation in one place! Here is just a sampler.

1. How do you get that all farmers plant just one variety of soybean? There are dozens if not hundreds of varieties available at any given moment. In fact, farmers probably have never had as wide a selection of varieties to choose from then they do now.

2 Use more herbicides? Have you ever heard of economics? Farmers do not spray for the fun of it. Biotech soybeans have allowed them to switch from older herbicides to newer ones that have smaller environmental footprints. It has allowed them to stop plowing the soil prior to planting, saving fossil fuels, preventing erosion and lowering greenhouse gas emission.

3. Herbicide residue limits and application guidelines are set by the EPA. No reputable study has found issues with consumer health.

4. Farmers might be dependent on companies for seed, but before that, farmers have been depended on companies for seed (yes, they have been buying seed for almost a century, pesticides (yep, they have used these since WWII) and tractors. Come 2014, when patents expire, they can save their own soybean seed.

5. Soybean expansion in Brazil is driven by consumer demand from Asia. That demand is independent of biotech. IF anything, the higher yields of biotech soybean limit the amount of land converted to agriculture.

Posted by Dr. Wayne Parrott on Apr 13, 2012 11:21 AM

Thank you for your comments. Firstly, I was in error when I suggested that only a single genetic variety of soy was used in GM soy production practices - as you said, multiple varieties are generally used to diversity. That error has been corrected above.

However, the remainder of the article does not contain misinformation. The debate about GM crop production is real and contentious, and I hope that interested readers will continue to engage with and learn about the issues surrounding this practice. The point of the article is to emphasize that even a seemingly innocent meat-substitute like soy is associated with environmentally questionable production practices like GM use and the separate issue of production-induced habitat destruction. It may seem like these practices happen a world away - and sometimes they do. But, as consumers of soy food products, of animals that are fed soy diets, and of soy-containing biodiesel, we have a responsibility to keep asking these questions and, when possible, to make the most environmentally conscious purchasing decisions. Because the environment depends on our choices! And we depend on the environment. So, thanks again for your comments and for the research that you do. Engaging in this debate in a respectful way will undoubtedly bring us closer to figuring out the best way to produce food and sustain the environments we produce it in.

Judee

Posted by Miss Judith Lena Burr on Apr 23, 2012 4:49 PM