Dedicated to advancing scholarly and public understanding of the past, present, and future of western North America, the Center supports research, teaching, and reporting about western land and life in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Center Researcher Contributes to Major Report on Climate Change in California

Photograph: Fragile Oasis via Flickr

This summer, the California Energy Commission published a major report assessing the state's vulnerability to climate change. The report looked at threats to infrastructure and human health, the effects of climate change on agriculture, water resources and wildfires, and sought to identify the most vulnerable ecosystems in the state.

Maria Santos is an ecologist and postdoctoral scholar at the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

The culmination of 18 months of work, the report brought together contributions from over 120 researchers, among them the Center's postdoctoral scholar, Maria J. Santos, who co-authored the paper "Identifying Vulnerable Species and Adaptation Strategies in the Southern Sierra of California Using Historical Resurveys."

Santos and her colleagues focused on a transect of the southern Sierra Nevadas that includes Yosemite National Park, an area whose flora and fauna had been extensively surveyed in the early to mid 20th century. By comparing present-day observations with the historic data, the team was able to see how small mammals changed their ranges over the last century. Moreover, because the Yosemite transect contains both developed and protected areas, the team was able to gauge the effect of human actions as well.

The study found that species at high altitudes reacted differently to direct and indirect effects of climate change than did those at mid and low elevations. While their most suitable habitats tended to move to lower elevations, the animals themselves tended to move to higher altitudes in response to changing conditions, suggesting that the adaptive capacity of a number of species to climate change may be limited.

Santos says that the wealth of evidence provided by the historical resurvey will make it possible to develop better models for how future climate change could impact habitats and the species that depend on them.

The complete report is available from the California Energy Commission.

Read the report by Maria J. Santos, Craig Moritz and James Thorne »

California as an "Island": Finding Grains of Truth in Misbegotten Maps

Julie Sweetkind-Singer, head librarian, Branner Earth Sciences Library & Map Collections, with some of the maps depicting California as an island. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

The Stanford Libraries have acquired a trove of nearly 800 historic maps that all share one grevious error: they depict California as an island floating off of the West Coast of North America. Donated by the prominent collector Glen McLaughlin, these European and Asian maps date from the 1600s to as late as the 1860s.

The Stanford News Service spoke to the Center's executive director, Jon Christensen, and our visiting fellow Rebecca Solinit, about how these maps – while utterly wrong – speak to something essentially right about the idea of California as an island:

According to Christensen, "Californians often think of themselves as an island. Bio-geographically, it's still very much an island," with its unique Mediterranean climate at the edge of a continent.

"California is surrounded by deserts and mountains, so much so that it might as well be an island," said Rebecca Solnit, author of Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. "It has 2,000 species of plants found nowhere else on the Earth, as well as a lot of endemic butterflies, reptiles and other critters."

Comparative Wests: A Summer of Creating, Restoring, and Maintaining Country

The Comparative Wests Project at Yulpu in Martu Country, Western Desert, Australia, on the morning of August 18, 2012. Pictured are Stanford and Native American participants with Martu Traditional Owners from Parnngurr Aboriginal Community and Rangers from Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa. Photograph: Don Hankins.

While “country” and “nation” are sometimes used synonymously, a country has a sense of home and landscape that often distinguishes it from the more administrative phenomena that define a nation. Today, many countries persist in – sometimes in spite of – the nation states that engulf them. Emblematic among these are the Indigenous lands and societies of Western North America and Australia, where despite common assumptions of collapse, Indigenous countries fluoresce, often beneath the scope and authority of the nations that claim them.

Over the course of August, the Comparative Wests Project at the Bill Lane Center for the American West convened in Australia to initiate a comprehensive exploration of the social and ecological processes through which such countries in Western North America and Western Australia emerge, change, and persist. The project implemented a groundbreaking, multi-disciplinary program of exchange and research – assembling scholars, policy makers, artists, journalists, land managers, curators, Traditional Owners, and First Nations representatives from the American West, Canada, and Australia – to investigate the processes and implications of creating, using, transforming, restoring, and maintaining the “countries” that continue to define the Wests.

Researching at Stanford, Reflecting on American Indian Identity

Photo: Left to right: Maurice Patterson, Director, “Oriental Korein Band”; Dolores Jean McLaughlin, Hunkpapa Sioux from Fort Yates, No. Dakota, and “Queen of the Oriental Band”; Howard Keik, Mayor of Casper, Wyoming; and Howard Evans, “Captain of the Guild, Korien Temple,” at the All-American Indians Days Pageant, Sheridan, WY, 1954. Miss American Indian “Miss America” Archive, c. 1950-1960, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University

This summer, the visiting researcher Cindy Ott spent time at the Center delving into the Stanford University archives. One collection that particularly intrigued her was the papers of the Miss American Indian Pageant, which was held annually in Sheridan, Wyoming between 1953 and 1985. “They reveal surprising collaborations among American Indian communities and the Shriners who organized the pageant,” she says, “collaborations and forms of cooperation that resist simple categorizations of us vs. them, or Indian vs. non-Indian identity.”

Ott says that she was struck by images like the one above, which depicts a young contestant alongside Shriners in Orientalist attire on parade through the streets of Sheridan, as three Native Americans view them from curbside. She says that the Miss American Indian archives document through written and visual sources how an ideal American Indian woman was defined at the time, and by whom and how those determinations were made.

Ott, an assistant professor of American Studies at Saint Louis University, is working on a research project entitled “Indians Making History,” examining how American Indian communities have documented their past and perpetuated their heritage in the last half-century. Some of the questions this project raises are: What are the dynamics and mechanisms by which American Indians reconcile their own experiences in a modern globalized world with the persistently romantic expectations of what it means to be Indian? What do Indians nowadays preserve from their own lives to perpetuate Indian heritage for future generations? She especially draws on Indians’ use of photographs, food, and land preservation, and the connections among them, to explore this topic.

Examining the Past of "America's Serengeti" on NationalGeographic.com

Through the Center's internship program, Michelle Berry is spending her summer at at the American Prairie Reserve, a Montana-based nonprofit that acquires and manages land trusts in the West. Recently, Michelle wrote a report describing her work mapping the boundaries of historical wildlife populations on the great plains. This week, The National Geographic Society's NewsWatch blog published her report. Berry writes:

"Today, the plains are barely recognizable from the descriptions provided by the journals of Lewis and Clark. During the 1800s a series of localized extinctions occurred across the American prairie, instigated in large part by the arrival of fur trappers (who heard about the abundance of animals encountered by the expedition) and increasing numbers of settlers (thanks to steamboats, wagon trains and railroads). An estimated 30 million bison were reduced to a few hundred, pronghorn numbered in the low thousands, and elk, along with predators like grizzlies and wolves, completely disappeared."

Theodore Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch, the “Walden Pond of the West,” Threatened by North Dakota’s Oil Boom

NPR's Morning Edition today has a story by the Rural West Initiative's director, John McChesney, about the threat posed by energy development to the site of Theodore Roosevelt's North Dakota ranch.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch in North Dakota is often called the “Walden Pond of the West.” But Roosevelt’s ranch today is in the midst of an oil boom that is industrializing the local landscape. Critics say a proposed gravel pit and a bridge could destroy the very thing that made such a lasting impression on Roosevelt: the restorative power of wilderness.

It’s not easy to reach the place that Roosevelt said created the best memories of his life. Over 30 miles of dirt road, then and a mile-and-a-half hike, lie between a visitor and the ranch. Roosevelt National Park Superintendent Valerie Naylor drove me out on a Sunday. We didn’t see another person at the ranch site, which sits on the banks of the Little Missouri River.

Naylor showed me the old hand-dug well and the ranch house’s massive foundation stones, cut from granite. “That’s what’s so special about the Elkhorn ranch,” she told me, “We don’t have anything that’s reconstructed here – we just have a site and it’s the way that it was – for the most part – when Roosevelt first found it in summer of 1884. So it’s very special.”

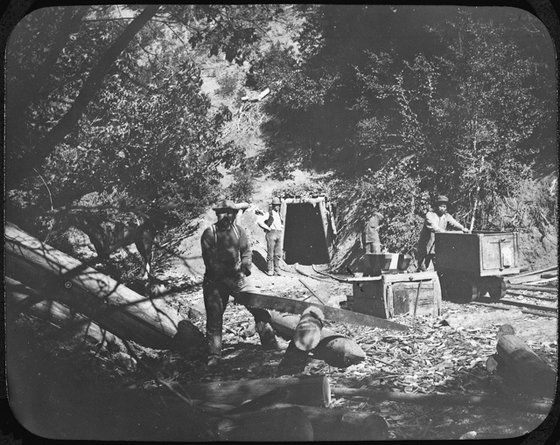

Gold fever heats up again in California's Mother Lode

Photo: Historical Gold Rush mine, National Archives, via Flickr

California has caught gold fever again.

Gold prices are at all-time highs. Signs of a new gold rush are popping up all along Highway 49 through the Mother Lode: grizzled prospectors panning in the creeks, new underground mines preparing to go into production, rampant mining-stock speculation, boosterish media coverage and even an old-fashioned salted-mine hoax.

The timing is perfect for a new gold rush, says Jack Mitchell, publisher of the weekly Ledger Dispatch in Amador County. The economy is "sucking wind" in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, he says, and "there is a strong belief that the real gold has not been found yet."

"Today's Gold Price" is posted daily behind the front desk at the historic Holbrooke Hotel in Grass Valley: "One Ounce - $1,593.00" the sign read when I checked in a couple of weeks ago.

Read the rest of Jon Christensen's report in the San Francisco Chronicle's "Insight" section »

California's Mixing Bowl: The Delta's Crucial Role in a Thirsty State

Photo: Greg Balzer via Flickr

Our interactive digital environmental history collaboration on the Delta with KQED and the San Francisco Estuary Institute was prominently featured and called out in a story on the PBS NewsHour last night:

This is a great sign of how such good, solid, important, in-depth work can have great legs. And it is echoed by the many other ways that people keep talking about and pointing to this work, as important in itself, and as an example of the kinds of things we all should be doing more of in environmental and science communications, deeply informed by history and the humanities.

Well deserved kudos to Geoff McGhee, Creative Director for Media and Communications here at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, and our collaborators at SFEI — including former Bill Lane Center intern Alison Whipple — and our media fellow from KQED, Lauren Sommer.

See the rest of the story with a link to the visualization at PBS Newshour »

Unearthing the Histories of Montana's Prairie Wildlife

By Michelle Berry

M.S. Earth Systems, 2014

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

“Immense” was the word Meriwether Lewis used consistently to describe the extent of prairie wildlife during his great transcontinental expedition; “We saw immense quantities of game in every direction around us as we passed up the river: consisting of herds of Buffalo, Elk and antelopes with some deer and wolves” (April 17th, 1805). Today, the plains are barely recognizable from the descriptions provided by Lewis. During the late 1800’s and early 1900s, the combined actions of homesteaders, fur trappers, and ranchers lead to a massive defaunation of the American prairie. Populations of bison, wolves, and grizzly bears went entirely extinct. Since 2001, the American Prairie Reserve (APR) has been working to restore the prairie ecosystem in northeastern Montana and create an educational nature reserve that will be open to the public. As part of their vision, the completed reserve will incorporate all the wildlife species that once inhabited the area in their natural abundances.

“Immense” was the word Meriwether Lewis used consistently to describe the extent of prairie wildlife during his great transcontinental expedition; “We saw immense quantities of game in every direction around us as we passed up the river: consisting of herds of Buffalo, Elk and antelopes with some deer and wolves” (April 17th, 1805). Today, the plains are barely recognizable from the descriptions provided by Lewis. During the late 1800’s and early 1900s, the combined actions of homesteaders, fur trappers, and ranchers lead to a massive defaunation of the American prairie. Populations of bison, wolves, and grizzly bears went entirely extinct. Since 2001, the American Prairie Reserve (APR) has been working to restore the prairie ecosystem in northeastern Montana and create an educational nature reserve that will be open to the public. As part of their vision, the completed reserve will incorporate all the wildlife species that once inhabited the area in their natural abundances.