Out West Blog

Notes, photos and updates from the Center's student researchers and summer interns working at organizations across the region.

Understanding Resilience in an Age of Change

B.S. in Earth Systems, 2012

Summer Intern at the San Francisco Estuary Institute

Read about our summer interns on the Out West student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Had you asked me four months ago about “the new ecological world order,” I might have given you a blank stare – even after graduating with a degree in the environmental sciences. Luckily, my Bill Lane Center internship at the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) gave me a chance to study Anthropocene-era conservation. I quickly learned how much climate change has altered the ecological world order, such that conventional conservation and restoration approaches are often inappropriate and even unsuccessful. With the SFEI team, I addressed this problem by donning a new mask, metaphorically at least. Together, my SFEI advisors and I adopted the two-faced gaze of Janus, the Roman god of gateways, looking both forward and backward in efforts to understand how we might design functional landscapes in a changing world.

Had you asked me four months ago about “the new ecological world order,” I might have given you a blank stare – even after graduating with a degree in the environmental sciences. Luckily, my Bill Lane Center internship at the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) gave me a chance to study Anthropocene-era conservation. I quickly learned how much climate change has altered the ecological world order, such that conventional conservation and restoration approaches are often inappropriate and even unsuccessful. With the SFEI team, I addressed this problem by donning a new mask, metaphorically at least. Together, my SFEI advisors and I adopted the two-faced gaze of Janus, the Roman god of gateways, looking both forward and backward in efforts to understand how we might design functional landscapes in a changing world.

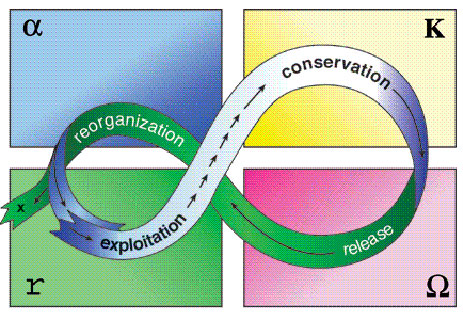

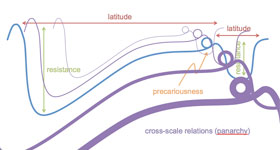

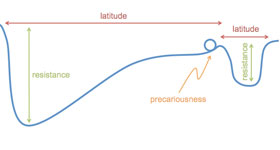

SFEI is in the process of developing an interdisciplinary research institute called the Center for Resilient Landscapes, and my somewhat daunting summer task was to clarify what “resilient landscapes” really are. The new Center will build on the strengths of existing SFEI programs in historical ecology, watershed and wetland science, and conservation biology, combining these programs‘ individual strengths to focus on creating dynamically functioning landscapes. Though ecologists, social scientists, and policymakers intuitively know what “resilience” means, it‘s hard to pinpoint a definition that renders the term useful to local managers. Thus, I spent a good portion of my summer reviewing the relevant literature – analyzing, annotating, and summarizing what “resilience” might mean to the SFEI team.

SFEI is in the process of developing an interdisciplinary research institute called the Center for Resilient Landscapes, and my somewhat daunting summer task was to clarify what “resilient landscapes” really are. The new Center will build on the strengths of existing SFEI programs in historical ecology, watershed and wetland science, and conservation biology, combining these programs‘ individual strengths to focus on creating dynamically functioning landscapes. Though ecologists, social scientists, and policymakers intuitively know what “resilience” means, it‘s hard to pinpoint a definition that renders the term useful to local managers. Thus, I spent a good portion of my summer reviewing the relevant literature – analyzing, annotating, and summarizing what “resilience” might mean to the SFEI team.

Resilience is a paradox of change and persistence. At SFEI, we consider resilient landscapes to be capable of recovering dynamically from perturbations, maintaining their basic function and structure in the face of change. The new Center will focus on building resilience by developing locally appropriate, long-term restoration strategies at sufficient scale for adaptation over time. Working with government agencies, land trusts, and local communities, the SFEI team will attempt to design landscapes that sustain natural hydrologic processes, support native species, and provide ecological services. This type of nuanced conservation work is challenging but important. It draws upon historical patterns and processes with an eye toward modern values and future conditions.

My time on SFEI‘s historical ecology team gave me a small taste of what the new Center will be capable of accomplishing. I focused my research on understanding historic species distributions in a handful of key watersheds and riverine systems in California. Using archival materials, I helped the team understand how California watersheds functioned in the early nineteenth century and how they might best function in the future. In addition to my literature reviews, I analyzed species collection databases, visited archives, digitized California maps, reviewed papers, and copyedited reports. These activities gave me a taste of the different kinds of work that go into historical ecology projects.

Whether the team at SFEI was analyzing old maps or proposing new restoration strategies, they consistently brought a critical eye and an optimistic approach to their work. As my first summer spent almost entirely in an office, I had to get used to sitting in a desk for eight or nine or even ten hours a day. I‘m glad my first desk job was at SFEI. With afternoon walks, yoga classes, and a social group of people surrounding me, I had a great work environment. The people at SFEI were curious about my aspirations and goals, and they cared about the trivial stuff of my day-to-day well being. Though I maintained a smile throughout my going-away lunch, it was hard not to cry. The team was dedicated, creative, encouraging, and just plain kind. Working at SFEI taught me about the type of colleagues I will search out in the future, and I only wish I could have stayed to help inaugurate the Center for Resilient Landscapes.

Whether the team at SFEI was analyzing old maps or proposing new restoration strategies, they consistently brought a critical eye and an optimistic approach to their work. As my first summer spent almost entirely in an office, I had to get used to sitting in a desk for eight or nine or even ten hours a day. I‘m glad my first desk job was at SFEI. With afternoon walks, yoga classes, and a social group of people surrounding me, I had a great work environment. The people at SFEI were curious about my aspirations and goals, and they cared about the trivial stuff of my day-to-day well being. Though I maintained a smile throughout my going-away lunch, it was hard not to cry. The team was dedicated, creative, encouraging, and just plain kind. Working at SFEI taught me about the type of colleagues I will search out in the future, and I only wish I could have stayed to help inaugurate the Center for Resilient Landscapes.

Read more at the Out West Blog for Summer Interns »

Fighting the Good Fight

B.A. in Biology, 2013

Summer Intern at Yellowstone National Park

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

I started the summer with next to no knowledge about North American lithic technology, plains archaeology, Yellowstone National Park, or cultural resources management. Now, I can identify and date diagnostic projectile points up to 10,500 years old, hold an intelligent conversation about prehistoric plains chronology, navigate my way through a bison jam, and appreciate the subtler points of Section 106 and Section 104 mandates. It’s hard to imagine that I’ve already been here for three months, and that it’s now time to leave. I feel like I could spend the rest of my life in Yellowstone and just begin to scratch the surface.

I started the summer with next to no knowledge about North American lithic technology, plains archaeology, Yellowstone National Park, or cultural resources management. Now, I can identify and date diagnostic projectile points up to 10,500 years old, hold an intelligent conversation about prehistoric plains chronology, navigate my way through a bison jam, and appreciate the subtler points of Section 106 and Section 104 mandates. It’s hard to imagine that I’ve already been here for three months, and that it’s now time to leave. I feel like I could spend the rest of my life in Yellowstone and just begin to scratch the surface.

The mountain of work bequeathed to the archaeologists in Yellowstone is enormous. Most of the work comes in the form of compliance requests – every federal project that could feasibly affect cultural resources in the park needs to be approved by the park archaeologist. In a place as culturally rich as Yellowstone, the projects seeking approval pile up quickly. Additionally, there are boxes upon boxes of backlogged ‘problem artifacts’—remnants from bygone contracted archaeologists who never finished analyzing and cataloging their finds (or in some cases cataloged them incorrectly, which presents a host of new problems). A single person could occupy themselves for years trying to sort through the thousands of backlogged artifacts and projects. The job descriptions of Staffan and Robin, the park archaeologists, could read like war plans – defeat the compliance requests, conquer the mess of incomplete reports, do battle with the backlog.

Conservation in Action at the American Prairie Reserve

M.S. Earth Systems, 2014

Summer Intern at the American Prairie Reserve

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Last week I made my final trip up to the prairie reserve. On the evening before I left, I went for a run to saturate my senses with the landscape. I eventually came to a valley where I decided to perch on a cottonwood tree and watch the sun go down. I closed my eyes for a few moments, and when I opened them, I saw a buffalo bull a few hundred yards in the distance that must have wandered off on his own. I then turned full circle and realized that I was surrounded by four other bulls that were quickly approaching me. I was overcome with excitement: All of the journals I had read by Lewis and Clark, Edwin Denig, George Catlin and others suddenly came alive, and I imagined an endless grass-filled landscape bursting with millions of buffalo, elk, and antelope and thousands of cougars, wolves, and bears.

Last week I made my final trip up to the prairie reserve. On the evening before I left, I went for a run to saturate my senses with the landscape. I eventually came to a valley where I decided to perch on a cottonwood tree and watch the sun go down. I closed my eyes for a few moments, and when I opened them, I saw a buffalo bull a few hundred yards in the distance that must have wandered off on his own. I then turned full circle and realized that I was surrounded by four other bulls that were quickly approaching me. I was overcome with excitement: All of the journals I had read by Lewis and Clark, Edwin Denig, George Catlin and others suddenly came alive, and I imagined an endless grass-filled landscape bursting with millions of buffalo, elk, and antelope and thousands of cougars, wolves, and bears.

In his book Last Stand, Michael Punke writes, “For emigrants traveling west, sighting the first buffalo marked a signature moment in their voyage – true arrival on the frontier”. Seeing those five buffalo that night represented a frontier for me as well. This frontier is partly physical; I come from mountains and evergreens. Before this summer I had never been to Montana nor had I seen a prairie landscape. In fact, the prairie did not immediately make a big impression on me. At first it seemed like a large expanse of barren nothingness. But then I spent time tearing down a century-old ranch corral, and created just a little more open space so that those bison can roam freely. I also spent a night driving around with a spotlight searching for black-footed ferrets, North America’s most endangered mammal. At 3:30 AM I finally saw a pair of those narrow-set, green eyes peer up at me, and I knew I was seeing one of only 750 in the wild. I came to understand that nature is often invisible to us, but those parts are no less extraordinary than the parts that are conspicuous. I now feel a closer connection to this land than any other I have ever experienced.

Heyday Love

B.A. Candidate in English, 2013

Summer Intern at Heyday Institute

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

I had a magical summer in Berkeley, working for Heyday Institute. As the Events and Marketing intern, I learned a lot about planning and communication as well as about the publishing process.

I had a magical summer in Berkeley, working for Heyday Institute. As the Events and Marketing intern, I learned a lot about planning and communication as well as about the publishing process.

What I enjoyed:

1. Meetings. I was able to attend different types of meetings and observe how various parts of a publishing company work together. At marketing meetings, the publicity and events directors would meet with authors to discuss possible marketing strategies. At development meetings, the board of directors, publisher, development director, and events director would meet to discuss fundraising events for the organization. My favorites were launch meetings. There, everyone would get together to discuss book cover designs and titles. It was interesting to hear about the politics in making book covers. For example, if an author was working on a biography with the person the book is about, it is better to have just the author’s name on the book rather than adding “by.”

2. Experience. I received a lot of hands on experience in writing pitch letters and press releases for books. I was also able to have a lot of control over the events planning project for Soul Calling, being able to decide where and when I wanted events. Whenever I needed guidance, I knew I could ask my supervisors for help.

3. The environment. Although I had a main project to work on, every day was a surprise. For example, one day when I came to work Malcolm walked into the office and asked me to make a diorama of old California when current extinct animals were still alive. For the rest of the morning, I played with animal cutouts and fake grass. I was also able to attend events, such as the after party for the News for Native California Anniversary and Basket celebration. There, I was able to meet many people from the Heyday community.

Conclusions from working at the Yosemite Museum

By Molly O’Connor

B.S. Candidate in Computational Imaging, 2014

Summer Intern at the Yosemite Museum

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

When I was about to head up to the Yosemite Museum at the beginning of the summer, one of the most confounding questions people asked me was what I was going to be doing there. I had vague ideas of researching things and putting them online, but I was also under the impression that I might be emptying mousetraps for eight hours a day.

When I was about to head up to the Yosemite Museum at the beginning of the summer, one of the most confounding questions people asked me was what I was going to be doing there. I had vague ideas of researching things and putting them online, but I was also under the impression that I might be emptying mousetraps for eight hours a day.

Two months after my initial confusion, you might ask again what exactly I’ve been doing all summer. And the answer (besides chain-drinking tea) is, well, everything. Because that’s what the people who take care of the museum’s collections need to do – everything. I dusted cabinets, changed lightbulbs, covered shelves with tyvec, and gathered climate monitors. I researched, asked questions, cataloged an Eadweard Muybridge photograph, and photographed nearly one hundred rocks so that I could select a dozen or so to put on a web page about the geological collection. It might have felt like grunt work some of the time, but even the little operations are necessary to take care of the collections. I may have spent hours plugging information about baskets into spreadsheets, but those spreadsheets were the necessary first step before designing a cultural exhibition for the next summer.

Yellowstone Over Time

By Quinn Walker

B.S. Candidate in Human Biology

Summer Intern with Yellowstone Heritage and Research Center

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

At the beginning of the summer, family and friends kept asking me what exactly I was doing in Yellowstone National Park. “Well,” I said, “I’m working in the Heritage and Research Center.” “Mmhmm…” they would doubtfully reply. “In the museum collection,” I’d add. “Um…” they would say. “You are so skeptical,” I’d sigh. “How can I put this? I catalog artifacts (clean, photograph, and label them before entering the details into the database and storing them), do inventory of items we already have, design exhibits, and give tours to visitors. I deal with pests, vacuum the processing room, and make perfectly sized boxes out of cardboard and a box cutter.” By this point there is silence. “That’s nice,” they say. And yes, it is nice. It’s also beautiful, fascinating, and an incredibly valuable experience.

At the beginning of the summer, family and friends kept asking me what exactly I was doing in Yellowstone National Park. “Well,” I said, “I’m working in the Heritage and Research Center.” “Mmhmm…” they would doubtfully reply. “In the museum collection,” I’d add. “Um…” they would say. “You are so skeptical,” I’d sigh. “How can I put this? I catalog artifacts (clean, photograph, and label them before entering the details into the database and storing them), do inventory of items we already have, design exhibits, and give tours to visitors. I deal with pests, vacuum the processing room, and make perfectly sized boxes out of cardboard and a box cutter.” By this point there is silence. “That’s nice,” they say. And yes, it is nice. It’s also beautiful, fascinating, and an incredibly valuable experience.

I will never forget my summer in Yellowstone (or, probably, the hundreds of random facts I now know about the nation’s first national park). I learned why the park holds such an important place in the world’s conservation efforts. Of course, Yellowstone couldn’t have happened without the contributions of countless individuals, such as Thomas Moran, John Colter, and Horace Albright. For my final exhibit, I chose to elaborate on one of those people. Ole Anderson was a Swedish implant to the park in its very early days. He set up wooden racks within the hot spring terraces. The hot springs, which are part of Yellowstone’s impressive thermal features, would coat specimens with layers of travertine (limestone) and create an impressive and unique souvenir. When I saw some of the horseshoes we have in the collection, I knew this was what I wanted to do. As I studied, I fell in love with the stories in the collection. The people who explored the park became my companions, and I couldn’t be happier about that.

Working for a Watershed; Conservation on the Henry’s Fork River

By Nessarose Schear

B.S. Earth Systems, Biosphere

Summer Intern with Henry's Fork Foundation

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

It feels strange to be back in a city after spending the whole summer with the Tetons and Yellowstone as my backyard. After weeks of a smoky skyline and blood red sunsets, caused by nearby forest fires, the clear New England sky of Massachusetts is disorienting.

It feels strange to be back in a city after spending the whole summer with the Tetons and Yellowstone as my backyard. After weeks of a smoky skyline and blood red sunsets, caused by nearby forest fires, the clear New England sky of Massachusetts is disorienting.

This summer was an incredible opportunity to participate in important conservation work and research and I look forward to seeing how the data we collected impacts the future management of the Henry’s Fork Watershed. This summer the crew of five interns and I, under the guidance of the excellent field leader Matt Cahoon, surveyed tributaries to the Henry’s Fork River. We worked mostly in Grand Targhee National Forest and Harriman State Park. Our work was focused on the native trout species, the Yellowstone Cutthroat trout, checking in on populations that had been surveyed around ten years ago. The cutthroat are threatened by invasive rainbow and brook trout that were introduced historically by anglers and by human activity such as cattle gazing and irrigation. In addition to research we also worked on some conservation projects to mitigate and reverse erosion, putting up fences and planting native willows and grasses along the banks of the Henry’s Fork. Luckily for the Fork, Henry’s Fork Foundation (HFF) is working hard on all fronts to make sure the river and its ecologic services are preserved.

What Do People Talk About When They Talk About Parks?

By Monica Climaco

B.A. Candidate in Urban Studies, 2013

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

One of the projects that I have been working on during my time here at the Bill Lane Center for the American West is answering the question that makes up the title of this post: What do people talk about when they talk about parks? As an Urban Studies major, I have read my share of works both endorsing and attacking parks and natural spaces in urban areas. From local politicians, to critics and activists, to members of non-profit organizations, to researchers and professors, it seems that everybody has something to say about what is good and what is bad about parks, or how parks should be. I myself am an advocate for parks and natural spaces in cities; I don’t think the City Nature team would have allowed me to join them if I were not. However, there is an argument against parks that resonates with me: Stanton Jones and Arthur Graves reasoned that public parks (and those who design and manage them) do not really take people’s needs into consideration. Therefore, these spaces are misunderstood and misused. Jones’ and Graves’ argument spurred me to determine what people—those who actually use and visit the parks often—are saying about parks. What features do they look for in a park? What makes them come back? Conversely, what are characteristics of a park are not attractive to them? What causes them to never want to return?

One of the projects that I have been working on during my time here at the Bill Lane Center for the American West is answering the question that makes up the title of this post: What do people talk about when they talk about parks? As an Urban Studies major, I have read my share of works both endorsing and attacking parks and natural spaces in urban areas. From local politicians, to critics and activists, to members of non-profit organizations, to researchers and professors, it seems that everybody has something to say about what is good and what is bad about parks, or how parks should be. I myself am an advocate for parks and natural spaces in cities; I don’t think the City Nature team would have allowed me to join them if I were not. However, there is an argument against parks that resonates with me: Stanton Jones and Arthur Graves reasoned that public parks (and those who design and manage them) do not really take people’s needs into consideration. Therefore, these spaces are misunderstood and misused. Jones’ and Graves’ argument spurred me to determine what people—those who actually use and visit the parks often—are saying about parks. What features do they look for in a park? What makes them come back? Conversely, what are characteristics of a park are not attractive to them? What causes them to never want to return?

To answer these questions, I decided to scour Yelp.com for reviews of parks in the City of Los Angeles, one of the areas that the City Nature team is focusing on. Not all of the parks that are listed under the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks appear on Yelp.com. However, more than 100 parks (big and small, famous and hidden gems, alike) are reviewed on the website. That number is plenty to work with for this project. Using a social networking site to gather data for research may not seem like the best choice, but it’s a cheap (read: free) and efficient alternative to conducting surveys at the hundreds of parks and natural spaces in LA. The Department of Recreation and Parks does not seem to have its own reviews, which adds to Yelp.com’s appeal. Plus, I thought that a social media platform that allowed users to write as they pleased would yield more varied and more interesting answers than a set of questions would.

Year of the Bay

By Anna Garbier

B.A. in Linguistics, 2012

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

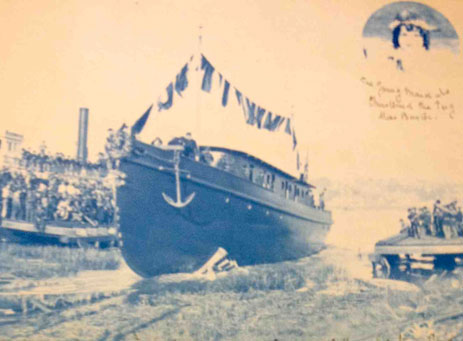

I’m sailing across the San Francisco Bay, on an 1891 scow schooner, operated by the San Francisco National Maritime Museum. It’s a public sail with fifteen or so passengers, including myself, and a few crewmembers. The historic vessel I’m on will soon become the physical centerpiece to an otherwise virtual crowdsourcing project headed by Jon Christensen at the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

I’m sailing across the San Francisco Bay, on an 1891 scow schooner, operated by the San Francisco National Maritime Museum. It’s a public sail with fifteen or so passengers, including myself, and a few crewmembers. The historic vessel I’m on will soon become the physical centerpiece to an otherwise virtual crowdsourcing project headed by Jon Christensen at the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

I’ve been invited onto the ship by the Captain, who now introduces me to the crew. He tells the crew that I’m a research assistant for a project called the Year of the Bay at the Bill Lane Center. He leaves it at that, and directs his attention towards the waters.

We round Angel Island and, in a lull of action, a crewmember turns to me. “So, what’s this Year of the Bay project?”

Inside the Bill Lane Center, we speak the language of corpus data, information mapping, geo-referencing, and crowdsourcing. We know what it means to create data-driven narratives, and what it means to conduct digital humanities research.

To digital humanities researchers, I say this: The Year of the Bay is a project that tests how crowdsourcing can be used to help humanities researchers obtain, tag, clean, and analyze a wide range of information. The project examines how crowdsourcing works by tracking and mapping the public’s interactions with a particular website (soon to be launched) that is designed and built for this experiment.

Vintage Motorcycles and Haunted Clocks

By Katrina Pura

B.A. Science Technology Society, 2013

Summer Intern with Yosemite Archives and Museum

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Prepare for the unexpected when you enter the Yosemite Museum collection room. The first time I was shown through the vault-like door and my supervisor switched on the lights in a manner reminiscent of the velociraptor scene in Jurassic Park, I was confronted with the oddest assortment of objects I had seen in my life. Amidst the bulk of the collection, a large pickled fish floated in yellow liquid, waterfall paintings were hung on racks all around the walls and the edge of a disused stone fireplace could be seen peaking halfway around a cabinet. Seemingly at random, my supervisor started pulling open drawers full of cups, weapons, feathers, jewelry and animal skins. Although I have since grown accustomed to this fascinating room, the novelty of my first visit set the tone of the internship for the summer. Because I spent two days in the museum and three in the Land Resources office, I was able to work on new and unexpected tasks every week.

Prepare for the unexpected when you enter the Yosemite Museum collection room. The first time I was shown through the vault-like door and my supervisor switched on the lights in a manner reminiscent of the velociraptor scene in Jurassic Park, I was confronted with the oddest assortment of objects I had seen in my life. Amidst the bulk of the collection, a large pickled fish floated in yellow liquid, waterfall paintings were hung on racks all around the walls and the edge of a disused stone fireplace could be seen peaking halfway around a cabinet. Seemingly at random, my supervisor started pulling open drawers full of cups, weapons, feathers, jewelry and animal skins. Although I have since grown accustomed to this fascinating room, the novelty of my first visit set the tone of the internship for the summer. Because I spent two days in the museum and three in the Land Resources office, I was able to work on new and unexpected tasks every week.

One of the highlights of my time in the museum occurred when my supervisor asked me to rewrite a label for a 1914 Indian Motorcycle. The label needed to detail the history of the Indian motorcycle company while also explaining the racist connotations of the brand name in a way that a middle school student could understand. Oh, and it needed to be five sentences or less. The assignment made me hyper-conscious of my word choice and gave me the opportunity to research something that I had never heard of before. Likewise, in creating a Wikipedia article on the early California artist, Chris Jorgensen and in updating the existing Yosemite Museum wiki I was able to greatly expand my knowledge of Yosemite history. In addition to these tasks, another highlight involved re-shelving rows of the Native American basket collection. I felt very lucky to handle such beautiful objects whose makers had invested months and even years of time and care into.

Running With the Wolves

By Julia Barrero

B.A. Candidate in History, 2014

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Maybe it was fate, or just serendipitous, or maybe I was subconsciously searching for it after spending weeks researching wolves this summer. However it happened, I recently stumbled across a song on YouTube: “Running With the Wolves” by Cloud Cult, which is precisely what I feel like I’ve been doing for the last ten weeks of this summer. Back in June, when I settled on studying Idaho’s wolf management policy as part of my independent research project for the Bill Lane Center, I also entered myself into a several month-long marathon; racing to absorb anything and everything about a subject about which I knew absolutely nothing.

Maybe it was fate, or just serendipitous, or maybe I was subconsciously searching for it after spending weeks researching wolves this summer. However it happened, I recently stumbled across a song on YouTube: “Running With the Wolves” by Cloud Cult, which is precisely what I feel like I’ve been doing for the last ten weeks of this summer. Back in June, when I settled on studying Idaho’s wolf management policy as part of my independent research project for the Bill Lane Center, I also entered myself into a several month-long marathon; racing to absorb anything and everything about a subject about which I knew absolutely nothing.

Why? Well, first off, I got this research gig as a bonus when I was offered the amazing opportunity to be a TA for the BLC’s Sophomore College Seminar on natural resource issues in the American West. This September, along with twelve rising sophomores, and five other faculty members, we’ll be studying fire policy, the health of fisheries, and land use, with southern Idaho as our backdrop. It’s an opportunity I am so grateful and excited to have, especially after having participated in the BLC’s last Sophomore College Seminar last summer, but as a student.

Mapping the Global Urban Water Crisis

By Jennifer Farman

B.A. Candidate in History, 2014

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

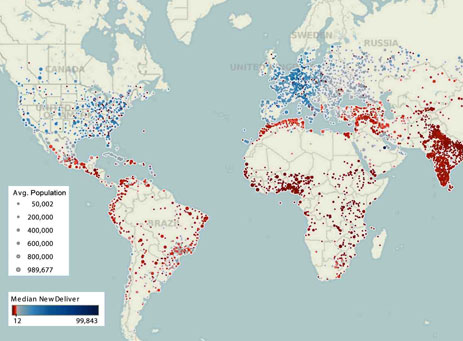

I first became interested in water issues last summer during my time exploring the complex role of water in the western United States as part of a Sophomore College course sponsored by the Bill Lane Center. This summer I have had the opportunity to investigate water issues on a global scale as a Research Assistant at the Center, where I have been exploring some exciting data on urban water availability as part of the “Global Cities” team of the City Nature project. With some excellent research from the Nature Conservancy as our base, my co-workers and I have spent the summer looking at many of the interesting interactions between urban growth and water availability. My research has focused on cities with current populations between 50,000 and 1 million people, as these cities will experience some of the most dramatic growth in the next 50 years. As the global urban majority continues to grow, these cities will face significant challenges in the areas of water quantity and quality, as well as in their capacity to deliver this water.

I first became interested in water issues last summer during my time exploring the complex role of water in the western United States as part of a Sophomore College course sponsored by the Bill Lane Center. This summer I have had the opportunity to investigate water issues on a global scale as a Research Assistant at the Center, where I have been exploring some exciting data on urban water availability as part of the “Global Cities” team of the City Nature project. With some excellent research from the Nature Conservancy as our base, my co-workers and I have spent the summer looking at many of the interesting interactions between urban growth and water availability. My research has focused on cities with current populations between 50,000 and 1 million people, as these cities will experience some of the most dramatic growth in the next 50 years. As the global urban majority continues to grow, these cities will face significant challenges in the areas of water quantity and quality, as well as in their capacity to deliver this water.

A Growing World Without Water

By Isabella Akker

B.S. in Earth Systems, 2013

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

Thirsty? Go to a water fountain, grab a bottle of water, or walk to a river. But what will you do thirty years from now? I’ve spent the last eight weeks looking for answers to questions surrounding what many of us take for granted—adequate, easy access to clean water.

Thirsty? Go to a water fountain, grab a bottle of water, or walk to a river. But what will you do thirty years from now? I’ve spent the last eight weeks looking for answers to questions surrounding what many of us take for granted—adequate, easy access to clean water.

Armed with a large dataset for over 6,000 cities worldwide, all with populations between 50,000 and 1 million, I worked to visualize and quantify worldwide water “stress” through a combination of proxy variables for measuring water quantity, water quality, and water delivery in these 6,000 cities. In turn, my team and I hope that this would demonstrate how prepared these cities are for growth both economically and socially.

Unsatisfied with the three variables’ inability to truly reflect the conditions “on the ground” for the more than 6,000 cities and over 195 countries, I decided to go further, and combined these three variables with others—including foreign investment, freshwater withdrawals, improved urban water and sanitation access, and population growth in a given country—to get a better sense of the challenges ahead of us as a global society dependent on water for survival. I am now working on visualizing the results of this model and creating an interactive webpage for others to modify my model and come to their own conclusions.

438 Miles Up: Analyzing Urban Nature from Orbit

By Alex Kindel

B.S. Symbolic Systems (Learning), 2014

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

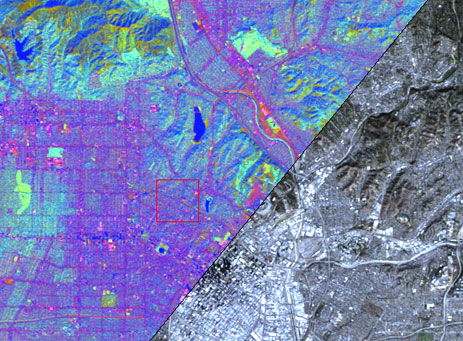

How is nature distributed in cities? In what ways can we understand the quality and experience of urban nature? These are just some of the many questions tackled by the interdisciplinary City Nature project this summer, which I've had the great fortune to be a part of.

How is nature distributed in cities? In what ways can we understand the quality and experience of urban nature? These are just some of the many questions tackled by the interdisciplinary City Nature project this summer, which I've had the great fortune to be a part of.

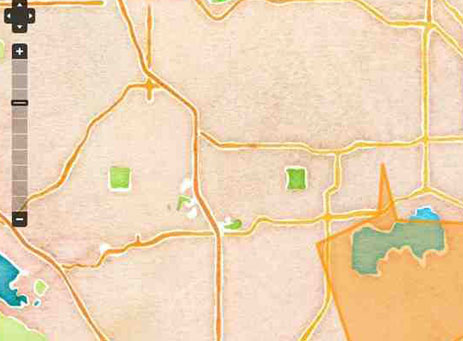

To answer these questions, we've taken a variety of approaches, from historical explorations of city parks to data mining on city planning documents. For my portion of the project, I chose to take a quantitative approach, primarily using methods from remote sensing. My main data source is Landsat 5, a satellite orbiting 438 miles above Earth. Landsat 5 carries an instrument called the Thematic Mapper (TM), which captures and processes numerous wavelengths of light reflected from the planet's surface. Using this imagery, I've spent the summer exploring and quantifying greenness for 36 of the largest cities in the United States.

My typical day in the office starts early in the morning in the computer lab, where I do the kinds of analysis that require a lot of heavy lifting on the computer's part. Landsat imagery is corrected for satellite conditions, transformed to generate greenness measures, split into smaller zones, and analyzed for statistical error. After spending a few hours in the lab, I take a lunch break, then head back to the shared office where the summer research assistants usually work. In the afternoon, I take the measures I've generated and explore different ways of categorizing and visualizing them.

Visualizing California's Water

By Christopher Kremer

Class of 2015

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Over the past ten weeks, I have worked with Geoff McGhee, the Bill Lane Center’s Creative Director for Media and Communications, to create an interactive information dashboard about California water management and conservation. I have used D3 and other Javascript data visualization libraries to develop interactive charts and graphs based on models from our partner Mitch Tobin at California Environmental Associates. I have also used geographic information systems technologies such as Quantum GIS to prototype maps about endangered species conservation and natural resource extraction, among other topics related to California’s water. Since we moved into the new office at the beginning of the summer, the once relatively empty workspace has grown up around us. We have added several top of the line computers for data visualization, as well as ample desk space for various creative projects. While our office, sandwiched between two others, was at first fairly quiet, it now hosts members of the City Nature team, too. It has been exciting to see the project evolve from the initial design, a constantly updated information panel with at-a-glance facts, to its current form, an interactive narrative platform that will see larger, more periodic additions. I have learned quite a lot from my summer work and am very excited to see our project in action.

Over the past ten weeks, I have worked with Geoff McGhee, the Bill Lane Center’s Creative Director for Media and Communications, to create an interactive information dashboard about California water management and conservation. I have used D3 and other Javascript data visualization libraries to develop interactive charts and graphs based on models from our partner Mitch Tobin at California Environmental Associates. I have also used geographic information systems technologies such as Quantum GIS to prototype maps about endangered species conservation and natural resource extraction, among other topics related to California’s water. Since we moved into the new office at the beginning of the summer, the once relatively empty workspace has grown up around us. We have added several top of the line computers for data visualization, as well as ample desk space for various creative projects. While our office, sandwiched between two others, was at first fairly quiet, it now hosts members of the City Nature team, too. It has been exciting to see the project evolve from the initial design, a constantly updated information panel with at-a-glance facts, to its current form, an interactive narrative platform that will see larger, more periodic additions. I have learned quite a lot from my summer work and am very excited to see our project in action.

Read more at the Out West Blog for Summer Interns »

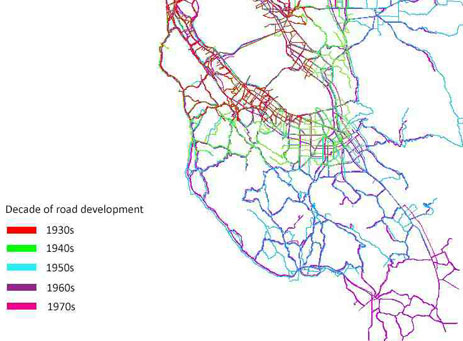

Digitizing Historic Roads of the Bay Area

By Alice Avery

B.A. in History, 2012

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with an innovative mining of planning documents, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives, in order to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

I’ll be honest: I was a little nervous about a summer internship under the Bill Lane Center for the American West because my worst grade at Stanford was in the most introductory of Earth Systems classes. The kind of grade from a supposedly easy class that makes people ask incredulously, “Really?” Despite being very interdisciplinary, the center is housed in the environmental sciences building. As a history major, I’m used to using texts, interviews, diaries, and other static written sources to answer research questions. Given the prompt to research conservation history in California on my own, using a search engine would have been the most technological thing I did. But in July, armed with a handful of tutorials in GIS and four CDs of high-resolution historic road maps, I set out to analyze conservation history in the Bay Area through road and open space development in digital decade snapshots.

I’ll be honest: I was a little nervous about a summer internship under the Bill Lane Center for the American West because my worst grade at Stanford was in the most introductory of Earth Systems classes. The kind of grade from a supposedly easy class that makes people ask incredulously, “Really?” Despite being very interdisciplinary, the center is housed in the environmental sciences building. As a history major, I’m used to using texts, interviews, diaries, and other static written sources to answer research questions. Given the prompt to research conservation history in California on my own, using a search engine would have been the most technological thing I did. But in July, armed with a handful of tutorials in GIS and four CDs of high-resolution historic road maps, I set out to analyze conservation history in the Bay Area through road and open space development in digital decade snapshots.

LA EJ (Environmental Justice)

By Jared Naimark

B.S. Candidate Earth Systems, 2014

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

Because of international travels at the beginning of the summer, I arrived back on campus for my research on the City Nature Project a few weeks late. I was surprised to find out that in my absence, I had been assigned to the history team and tasked with investigating the history of urban parks in Los Angeles. At first I was nervous and disappointed. I knew nothing about historical research, and even less about LA - I thought I would rather research anywhere else. However, I realized that Los Angeles must have been chosen for a reason, and so I delved into the books and articles, searching for a way to approach my task through the lens of my own interests in environmentalism, human rights, and activism.

Because of international travels at the beginning of the summer, I arrived back on campus for my research on the City Nature Project a few weeks late. I was surprised to find out that in my absence, I had been assigned to the history team and tasked with investigating the history of urban parks in Los Angeles. At first I was nervous and disappointed. I knew nothing about historical research, and even less about LA - I thought I would rather research anywhere else. However, I realized that Los Angeles must have been chosen for a reason, and so I delved into the books and articles, searching for a way to approach my task through the lens of my own interests in environmentalism, human rights, and activism.

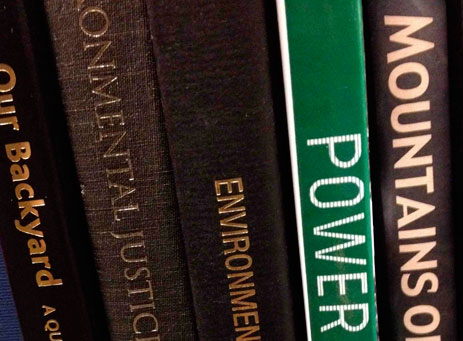

I quickly found my connection in the subject of Environmental Justice, EJ, for short. The EJ movement, with roots in the occupational health movement of the early 20th century as well as in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, links environmental sustainability to the health of urban dwellers. Throughout history and today, environmental health hazards such as toxic wastes and air pollution have disproportionately impacted low-income and minority communities. In response to this injustice, grassroots activists have come together to prevent the further pollution of their communities. After discovering what seems to be an unofficial EJ section in Green Library (see photo), I learned that many of the most important EJ battles have been waged in and around Los Angeles. From the superfund clean-up of the Stringfellow Acid Pits in the ‘80s, to the citizen inspired halting of the Nueva Azalea power plant in 2001, these pivotal activist victories not only ensured safe and sustainable local communities, but also put EJ on the map as a national issue.

Mining the Museum, Curating California, Pinning Down Public Memory

By George Philip LeBourdais

Ph.D. Candidate in Art History

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

On a balmy spring day in Palo Alto, one of my fellow art historians gloomily contemplated the contemporary usage of the word “curate.” What passes for “curating” today, she lamented? Often a sporadic relationship between a tumblr account and dramatic photography culled from a fashion magazine, designer’s website, or lust-worthy food blog.

On a balmy spring day in Palo Alto, one of my fellow art historians gloomily contemplated the contemporary usage of the word “curate.” What passes for “curating” today, she lamented? Often a sporadic relationship between a tumblr account and dramatic photography culled from a fashion magazine, designer’s website, or lust-worthy food blog.

My research this summer for the Bill Lane Center in downtown San Francisco at the California Historical Society (CHS) thus arrived like a breath of fresh air, even while I shuffled through low-lit underground vaults poring over old books, paintings, and photographs. In fact, “Curating California,” an ongoing project that Jon Christensen, Executive Director of the Bill Lane Center, conceived in collaboration with Anthea Hartig, the inspiring Director of CHS, demands that we refresh our understanding of the term:

Curate, in its nominative form, means one who cares for the development of souls, reminding us that a central mission of “curators” should be preserving things that help us understand our collective past and might positively affect our growth as social beings. Curating, in that sense, means caring about community.

Unsolved Mysteries and the Making of an Exhibit

By Maritza Urquiza

B.A Candidate in History

Read about our summer research projects on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Anyone who has been around me this summer has surely heard me talking, perhaps rambling once in a while, about Juana Briones. A friend commented on how I talk about her as if I had once known her. For the past seven weeks, I have been getting to know this incredible historical figure through my internship with the California Historical Society (CHS). I have been working with Marie Silva, an amazing CHS staff member, to research and locate primary sources for a future exhibit on the life and times of Juana Briones. Juana Briones was a fascinating nineteenth century California pioneer, who was also humanitarian, a landowner, a healer, and an early feminist, just to name a few words that would describe her.

Anyone who has been around me this summer has surely heard me talking, perhaps rambling once in a while, about Juana Briones. A friend commented on how I talk about her as if I had once known her. For the past seven weeks, I have been getting to know this incredible historical figure through my internship with the California Historical Society (CHS). I have been working with Marie Silva, an amazing CHS staff member, to research and locate primary sources for a future exhibit on the life and times of Juana Briones. Juana Briones was a fascinating nineteenth century California pioneer, who was also humanitarian, a landowner, a healer, and an early feminist, just to name a few words that would describe her.

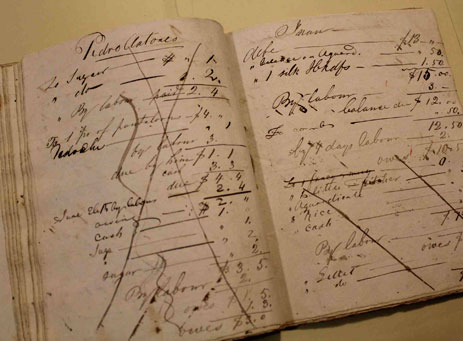

My summer has consisted of asking a wide range of research questions, uncovering sources and searching for clues that shed light on Juana Briones’ incredibly complex and captivating life. I have visited numerous repositories throughout the Bay area, searching through mission records, lithographs, maps, portraits, legal and land transaction documents, as well as translating nineteenth century Spanish manuscripts. Since sources that relate directly to Juana Briones are limited, I often have to search for other material that would shed light on an aspect of Juana Briones’ world. For instance, a potential visual that I found searching through a CHS collection includes an 1847 account book of Indian sailors (pictured above). Juana Briones was known for her humanitarian aid to sailors and this source can give us a clue to some of the sailors that Juana Briones might have come in contact with and even harbored in her house.

Mapping Los Angeles’ Park History

By Nicholas Biddle

B.S Candidate in IDMEN Energy ad Materials Engineering, 2014

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

How does a park system come to be? What is the motivation behind park creation? These are just two of the many questions that led us to create the City of Los Angeles park development map.

How does a park system come to be? What is the motivation behind park creation? These are just two of the many questions that led us to create the City of Los Angeles park development map.

The idea of the project was to build a historical map of Los Angeles parks. Since the start, the methodology has taken many turns and the vision of the final deliverable has greatly changed. We ran into our first roadblock when we could not find the establishment dates of Los Angeles’ parks. It soon became apparent that the city was not available to help with our request, so we took our research to the archives. From there, we gathered park opening dates from Los Angeles Times online archives and municipal annual reports with reasonable success. The vision and storyboard went through many evolutions based on the visualization service we were planning on using. In the end we decided to go with Neatline, a new program in need of a project daring enough to test it out. We were up for the job and have not looked back since.

How do Cities Measure "Social Capital"?

By Sarah Quartey

B.A. Candidate in Urban Studies, 2014

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

Here’s something that wasn’t initially on my bucket list: read the comprehensive plans for each of the 40 largest cities in the United States. It’s kind of funny how things like that happen. Anyway, let’s back up and explain how I found myself knee deep in the ever-so inspiring "Envision San Jose."

Here’s something that wasn’t initially on my bucket list: read the comprehensive plans for each of the 40 largest cities in the United States. It’s kind of funny how things like that happen. Anyway, let’s back up and explain how I found myself knee deep in the ever-so inspiring "Envision San Jose."

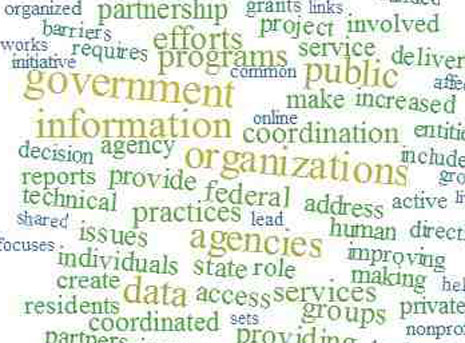

The CityNature research group is exploring why access to nature (defined as tree-lined boulevards, urban parks, backyard gardens) doesn’t scale up with population. We took a variety of approaches, and I found myself on the Semantics Team. The Semantics Team sought to understand how cities talk about nature – Is nature aesthetic? Economic? Recreational? Or is it something else altogether? In doing so, my other undergraduate teammate and I built a plain text corpus out of the 37 comprehensive plans we were able to get our hands on. This turned out to be no small task. I knew from the beginning that I wanted to talk about the social causes and effects of the physical urban design of city nature, and I realized I could use this painstakingly pieced-together corpus just for that purpose.

My research has focused on what city comprehensive plans refer to as “social capital.” Social capital is a collective term for “social networks and the associated norms of reciprocity” – it is, essentially, the power of human relationships rather than the power of an individual or even a collective group (Putnam, 2000). Social capital lies between the influence and capital of a single person and the power in a great number of people – social capital refers to neither Martin Luther King, Jr. nor the sum of the March on Washington, but instead to the congregation that attended in full force because of the strong ties between its members. I know, I know, it’s a mouthful.

A Trip to the Delta

By Jenny Rempel

B.S. in Earth Systems, 2012

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns and Research Assistants will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

As we nibbled on sack lunches in the minivan, I found myself asking if it was opposites day. Liquid gold from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta was flowing through a leveed canal some 20 feet above us. Somehow things were reversed: how had the islands wound up beneath the very water that made them islands? On my first field day with the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), it felt like I was following the Historical Ecology Team down the rabbit hole into a wonderland landscape. Luckily, this was just the team to help me understand the history behind this baffling locale.

As we nibbled on sack lunches in the minivan, I found myself asking if it was opposites day. Liquid gold from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta was flowing through a leveed canal some 20 feet above us. Somehow things were reversed: how had the islands wound up beneath the very water that made them islands? On my first field day with the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), it felt like I was following the Historical Ecology Team down the rabbit hole into a wonderland landscape. Luckily, this was just the team to help me understand the history behind this baffling locale.

Having spent the previous week copyediting a 400-page report on the region, I was eager to see this labyrinth inland delta in person. Reading of sunken islands and ever-taller levees does not fully convey just how whimsical this landscape looks today. But the 400-page report published by the Historical Ecology Program does not attempt to describe things as they are in the present. Instead, it focuses on what this landscape looked like 200 years ago. Four years of research revealed, from south to north in broad brushstroke generalizations: a series of broad riverine floodplains, tule-choked marshes laced with tidal channels, and tidal wetlands with rich riparian forests. Pretty different from the deep-set cornfields we were passing in our minivan.

The report is a tour-de-force from Alison Whipple, Robin Grossinger, Ruth Askevold, and the whip-smart team at SFEI. I’ve been lucky enough to join their ranks in Richmond, CA for a few brief summer months.

Filling in the Gaps: Mapping LA Park History

By Claudia Preciado

B.A. Urban Studies, 2012

Read about the CityNature project on the OutWest student blog. Over the summer, a team of undergraduate student researchers combined spatial analysis with innovative mining of planning document text, photographs, social media, and published historical narratives to explain why nature is unevenly distributed in and across cities.

Los Angeles has been home for me my entire life, which makes me one of the biggest proponents for public spaces and green spaces. Growing up in the city for me meant having my parents drive me to softball practice at the nearest park. That alone was reason enough to become a part of the City Nature project focused on Los Angeles parks. As part of the historical team, we were motivated by the question of how people use and interact with LA parks, through time and across boundaries.

Los Angeles has been home for me my entire life, which makes me one of the biggest proponents for public spaces and green spaces. Growing up in the city for me meant having my parents drive me to softball practice at the nearest park. That alone was reason enough to become a part of the City Nature project focused on Los Angeles parks. As part of the historical team, we were motivated by the question of how people use and interact with LA parks, through time and across boundaries.

Our research began with finding out more about the park system and how it evolved over time. By researching park histories, we hoped to find out more about why the public wanted parks to begin with (i.e. potential and previous uses). Through this research, we came across articles discussing the concept of usable parks for the people instead of perfectly groomed (stay off the) lawns. Issues of social equity and access were relevant across the 1920s and 1930s when Los Angeles witnessed a surge of parks.

From the initial research, our team decided to create a public, interactive way of accessing the information, articles, and photos we were finding. An accessible history, along with current information, on Los Angeles parks would allow others to also add and take ownership of their local parks. Creating a way to display this information became another task in the process.

Unearthing the Histories of Montana's Prairie Wildlife

By Michelle Berry

M.S. Earth Systems, 2014

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

“Immense” was the word Meriwether Lewis used consistently to describe the extent of prairie wildlife during his great transcontinental expedition; “We saw immense quantities of game in every direction around us as we passed up the river: consisting of herds of Buffalo, Elk and antelopes with some deer and wolves” (April 17th, 1805). Today, the plains are barely recognizable from the descriptions provided by Lewis. During the late 1800’s and early 1900s, the combined actions of homesteaders, fur trappers, and ranchers lead to a massive defaunation of the American prairie. Populations of bison, wolves, and grizzly bears went entirely extinct. Since 2001, the American Prairie Reserve (APR) has been working to restore the prairie ecosystem in northeastern Montana and create an educational nature reserve that will be open to the public. As part of their vision, the completed reserve will incorporate all the wildlife species that once inhabited the area in their natural abundances.

“Immense” was the word Meriwether Lewis used consistently to describe the extent of prairie wildlife during his great transcontinental expedition; “We saw immense quantities of game in every direction around us as we passed up the river: consisting of herds of Buffalo, Elk and antelopes with some deer and wolves” (April 17th, 1805). Today, the plains are barely recognizable from the descriptions provided by Lewis. During the late 1800’s and early 1900s, the combined actions of homesteaders, fur trappers, and ranchers lead to a massive defaunation of the American prairie. Populations of bison, wolves, and grizzly bears went entirely extinct. Since 2001, the American Prairie Reserve (APR) has been working to restore the prairie ecosystem in northeastern Montana and create an educational nature reserve that will be open to the public. As part of their vision, the completed reserve will incorporate all the wildlife species that once inhabited the area in their natural abundances.

Getting into California

By Sandy Chang

B.A. Candidate in English, 2013

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

On my second day at Heyday, Lillian, one of my supervisors, turned around from the passenger seat of the car and smiled, “Today is a great day for research. Let’s go hiking at a preserve one of our fall books is based on.”

On my second day at Heyday, Lillian, one of my supervisors, turned around from the passenger seat of the car and smiled, “Today is a great day for research. Let’s go hiking at a preserve one of our fall books is based on.”

Natalie, Lillian, and I had just finished a marketing meeting with authors Colburn Wilbur and Fred Setterberg about their upcoming book, Giving with Confidence: A Guide to Savvy Philanthropy. The meeting had lasted two hours, and we were all tired after a long discussion about ways to market their book through social networking, public media, and events. Therefore, we stopped by Pulgas Ridge for an hour of hiking before driving back to work. It’s moments like these that make working at Heyday a great experience. Although Heyday contributes amazing books to the literary world, the work environment is friendly and relaxing.

Heyday is a small non-profit publisher located in Berkeley, California. The organization exists to promote awareness and celebration of California’s many cultures, landscapes, and boundary-breaking ideas. It was originally founded by Malcom Margolin in 1974.

Gone Fishin'

By Daniel Perret

B.A. in Biology, 2013

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Yellowstone National Park is an international destination for people who love to fish, from casual stick-and-string dock anglers to hardcore wader-wearing fly-fishers. For thousands of years, people have utilized the bountiful piscine resources of the many creeks, lakes, and rivers that pepper the Yellowstone countryside.

Yellowstone National Park is an international destination for people who love to fish, from casual stick-and-string dock anglers to hardcore wader-wearing fly-fishers. For thousands of years, people have utilized the bountiful piscine resources of the many creeks, lakes, and rivers that pepper the Yellowstone countryside.

Hang on a second! Until very recently, no evidence of prehistoric (defined as pre-1750) fishing activity has ever been found within the park. Theories abounded as to the reason. Maybe the prehistoric Native American residents of the park held a cultural taboo against fish consumption? Did they simply lack the technology to exploit the resource? Or have our best archaeological efforts simply missed the traces?

In 2006, an excavation at an important new site near the northern park boundary proved the third option correct. The excavation team found two net-sinker weights, one on each side of the Yellowstone River. The net-sinkers are heavy, impressive affairs; large, ovate river cobbles with considerable notches worked into opposite sides. Subsequent excavations of the site reached a depth of four meters, where Paleo-Indian knives were recovered, indicating that the site had been occupied as early as 10,500 years before present (YBP). Although the net-sinkers themselves probably date to the late pre-historic period (3,000 YBP – 300 YBP), they represented the first evidence of fishing ever recovered in Yellowstone.

Fast forward six years. Two park archaeologists and I are back at this important area, performing a site condition assessment. We walk transects, eyes on the ground, on the prowl for lithic artifacts and possible threats to the site. I spot a large rock that looks suspiciously out of place, eroding out of the riverbank. I pick it up, dust it off, and see that this is no ordinary rock. Another net-sinker, and the third ever recovered!

Seeing Yosemite Through New Eyes

Photo: Sergio Rodriguez via Flickr

By Katrina Pura

B.A. Science Technology Society, 2013

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

Before my eight week internship began in the Land Resources Office of Yosemite National Park, I couldn’t have told you what exactly I would be doing. Vague ideas of filing papers and reading musty government maps filled my head. I had no idea what managing the land in a park nearly the size of Rhode Island would entail, but four weeks in with four more exciting weeks before me I can say that I do now. I realized the extent of what I have learned while reading an article my supervisor sent me last Monday. Titled “Land Rush at National Parks” from the Wall Street Journal, the article dealt with such issues as buying inholdings (private properties inside the park), using a reduced Land and Water Conservation Fund (the government mechanism for buying land) to purchase these properties and the necessity in some cases of working through third party conservation trusts to negotiate the deals. These references would have been unintelligible to me at the start of the internship but after their involvement in day-to-day discussion in the office, you can imagine how familiar they have become.

Before my eight week internship began in the Land Resources Office of Yosemite National Park, I couldn’t have told you what exactly I would be doing. Vague ideas of filing papers and reading musty government maps filled my head. I had no idea what managing the land in a park nearly the size of Rhode Island would entail, but four weeks in with four more exciting weeks before me I can say that I do now. I realized the extent of what I have learned while reading an article my supervisor sent me last Monday. Titled “Land Rush at National Parks” from the Wall Street Journal, the article dealt with such issues as buying inholdings (private properties inside the park), using a reduced Land and Water Conservation Fund (the government mechanism for buying land) to purchase these properties and the necessity in some cases of working through third party conservation trusts to negotiate the deals. These references would have been unintelligible to me at the start of the internship but after their involvement in day-to-day discussion in the office, you can imagine how familiar they have become.

Stories from Team Trout

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work. We’re excited to highlight their work with that of our distinguished partners: American Prairie Foundation, Henry’s Fork Foundation, Heyday, Yellowstone National Park, Yosemite Archives and Museum, and the San Francisco Estuary Institute.

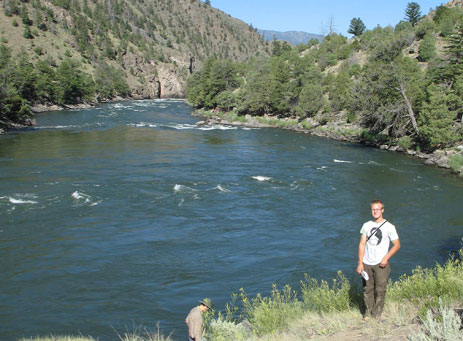

By Nessarose Schear

B.S. Earth Systems, Biosphere

Every morning the five other co-interns and I pack our packs, load up the ancient Suburban with field gear, and head out to remote creeks in the Henry’s Fork watershed. This area, especially the Henry’s Fork river, is considered some of the absolute best fly-fishing because of the huge wild rainbow and brook trout. Henry’s Fork Foundation (HFF) is the only organization advocating for the conservation of the watershed. They do everything; research, restoration, education, and negotiation with local farmers and businesses to make sure the watershed stays healthy.

Every morning the five other co-interns and I pack our packs, load up the ancient Suburban with field gear, and head out to remote creeks in the Henry’s Fork watershed. This area, especially the Henry’s Fork river, is considered some of the absolute best fly-fishing because of the huge wild rainbow and brook trout. Henry’s Fork Foundation (HFF) is the only organization advocating for the conservation of the watershed. They do everything; research, restoration, education, and negotiation with local farmers and businesses to make sure the watershed stays healthy.

A big indication of the health of the system is the health of the trout. That’s where we interns come into the picture. We are helping HFF re-survey streams that were surveyed around 10 years ago, to check in on the trout populations. While we care about the rainbow and brook trout, we really want to study the native Yellowstone cutthroat trout, which are easily outcompeted by the nonnative species.

Learning and Teaching Yellowstone’s History

By Quinn Walker

B.A. Candidate in Human Biology, 2015

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

As Jon, one of Yellowstone’s museum technicians, led a tour of the collection, I stood behind the tables. Jon had called me in to this group from Elderhostel, training for the day I would lead a tour on my own. I listened attentively, noting key historical points and interesting facts I could use in the future.

As Jon, one of Yellowstone’s museum technicians, led a tour of the collection, I stood behind the tables. Jon had called me in to this group from Elderhostel, training for the day I would lead a tour on my own. I listened attentively, noting key historical points and interesting facts I could use in the future.

Then one of the gentlemen in the group asked Jon about an artifact on the table. Jon grinned and turned to me. “I belieeeeeve I will let my lovely assistant, Sophia Snuffleupagus, answer this one. Sophia, they’ve got a question about the coated specimens.” I laughed. “Well, first of all, I only wish that was my name. But yes, I’d be super excited to tell you about them!”

Jon knew that I had begun planning my exhibit, as had the other two interns in the Curatorial Department of the Heritage and Research Center. Different members of the staff had taken us through the vast Yellowstone collections. We’d seen old jail doors, photo albums, mini-skirt uniforms from the 60’s, and full size mounted bears—and that’s just from the curatorial collections. The three-story HRC, as it’s fondly known, also houses a research library, archives, and geology, botany, and archeology labs (each with its own collection of artifacts).

Many objects are so distinct they require a new box be made for their storage from the materials down in the archive room. I’ve spent hours down in the basement, measuring, cutting, and gluing pieces together. We’ve become old hands at packaging--the objects vary in size, shape, and weight and this information all goes into the preparation for storage. Next Christmas is going to be a piece of cake.

As soon as I had seen the artifacts, I knew what I wanted to do for my exhibit. In the early days of the park, entrepreneurs had swooped in quickly, eager to make money off the majesty of ‘Wonderland’. One of these opportunists, Ole Anderson, had set up wooden racks within Mammoth Hot Springs. Visitors would place wire objects on these racks and, over five days, the Hot Springs coated them with layers of travertine (limestone) leaving visitors with glistening white souvenirs of their visit.

Jon looked on as I described the artifacts and Anderson’s life, and even went on to talk about the biology of the wolf skulls out on the table. With over 3.5 million visitors each year, the importance of educating Yellowstone’s public has never been higher. The Museum collection, and even just being in Yellowstone, gives one an amazing appreciation of both the history of the West and the beautiful and remarkable land that we sometimes take for granted.

Read more at the Out West Blog for Summer Interns »

Baskets on Baskets in the Yosemite Museum

By Molly O'Connor

B.S. Candidate in Computational Imaging, 2014

Read about our summer interns on the OutWest student blog. Throughout the summer, the Center's interns will be sending in virtual postcards, snapshots and reports on their summer work.

It’s possible there’s something wrong with me. I’m starting to like making spreadsheets. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not the only thing I’ve been doing here at the Yosemite Museum. I know the location of every bug trap, and the little research projects are particularly fun. Who’d have thought that a name of a man who taught at a Los Angeles community college fifty years ago would lead me to the achievements and love packed away into the yearbook of the 1950 class of the Yosemite Field School, shared with me after six decades of being tucked, lonely, in the dark of a shelf? Or that I’d graduate college with a halfway-decent knowledge of the number and placement of machine guns on WWII fighter jets?

It’s possible there’s something wrong with me. I’m starting to like making spreadsheets. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not the only thing I’ve been doing here at the Yosemite Museum. I know the location of every bug trap, and the little research projects are particularly fun. Who’d have thought that a name of a man who taught at a Los Angeles community college fifty years ago would lead me to the achievements and love packed away into the yearbook of the 1950 class of the Yosemite Field School, shared with me after six decades of being tucked, lonely, in the dark of a shelf? Or that I’d graduate college with a halfway-decent knowledge of the number and placement of machine guns on WWII fighter jets?

But my main job at the Yosemite Museum is working with American Indian woven baskets. My part-time counterpart, Katrina, and I are removing all of the baskets from their shelves in the Collections Room, covering each shelf with Tyvec so the baskets won’t catch on the foam padding, then replacing the baskets. My largest basketry responsibility, however, is to create spreadsheets with catalog numbers, details, and images of every single basket that each of the three Paiute/Miwok Indian demonstrators for the Museum have ever made.

There are literally hundreds.