Preventing Armageddon: 2010 Drell Lecture examines the road to nuclear arms elimination

What would a world without nuclear weapons look like, and how might it be achieved when Iran and North Korea are seeking the Bomb? The 2010 Drell Lecture brought together two Hoover fellows, both outspoken advocates of nuclear nonproliferation - former Secretary of State George Shultz and theoretical physicist Sidney Drell - in a conversation with former New York Times journalist Philip Taubman over the future of global nuclear disarmament.

BY AIMEE MILES

What would a world without nuclear weapons look like, and how might global leaders achieve the delicate political balance needed for its development? Is a nuclear nonproliferation agenda compatible with the contemporary demands of national and international security, or will the escalating threat of emerging nuclear rivals perpetually quash any hope of progress toward comprehensive nuclear reduction?

These dilemmas were among the weighty subjects of contemplation in discussion Monday hosted by Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC), titled "Working Toward a World Without Nuclear Weapons."

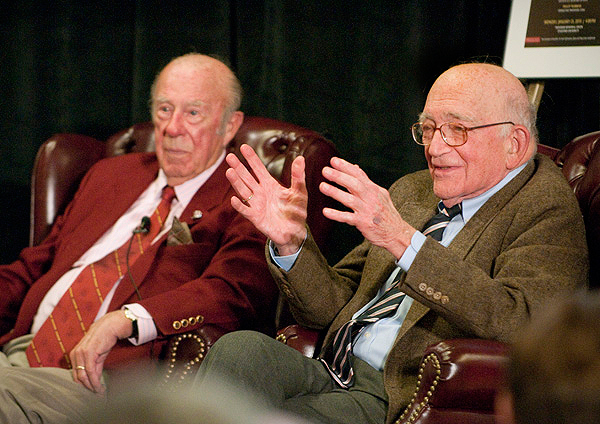

The 2010 Drell Lecture brought together two Hoover fellows and outspoken advocates of nuclear nonproliferation - former Secretary of State George Shultz and theoretical physicist Sidney Drell - in a conversation with former New York Times journalist Philip Taubman over the future of global nuclear disarmament.

Shultz and Drell, who became colleagues (and fast friends) after Shultz sought the technical counsel of the latter while serving as secretary of state under President Reagan, were both advocates of arms control and nuclear nonproliferation during the Cold War.

Former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, left, and physicist Sidney Drell addressed a full house at the symposium hosted by Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation.

They began their personal conversation years ago with recollections of the pivotal event that ended World War II and would define the future trajectory of both their careers - the leveling of Hiroshima by the world's first atomic bomb.

Hiroshima's lasting impression

When news of Hiroshima broke, neither man understood what an atomic bomb was, let alone what it could do - but the photographs that emerged from the din of destruction that enveloped that city (and later, Nagasaki) left a lasting impression of the immeasurable costs involved, Shultz recalled. "It was my first real impression of what Hiroshima was, just to see those pictures," he said.

The relief of entering a post-World War II era was quickly stifled as the mounting pathos of Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union began to settle in its place. Drell set to work on the Missile Defense Alarm System (MiDAS) and Corona projects, which aimed, respectively, to provide notice of Soviet ballistic missile launches and conduct satellite surveillance.

"Between August 1945 and 1960, I was a physicist teaching for a while at MIT, mostly here at Stanford," Drell remembered. "One day I got a phone call saying that wise hands in Washington realized that physicists, specifically, and scientists in general had played a very important part in winning World War II - winning it with radar, ending it with the atom bomb. But those individuals were no longer young … and it was thought that perhaps bringing a young generation of scientists into the work would be important for our national security."

Drell was among a handful of young scientists and academics invited to work during their summers "on problems of national importance." He was assigned to help figure out a way for orbiting satellites to obtain useful surveillance information - such as how to detect the launch of ballistic missiles halfway around the world by observing rising plumes of heat.

He was later called to Washington to do more extensive work on improving first-generation photo satellites. As the technology improved, Drell began to see its potential for supporting verification processes in nuclear treaties and promoting arms control. Recognition of his work in Washington eventually led to his collaboration with Shultz, who, as secretary of state under Reagan, was charged with the task of averting a nuclear crisis with the Soviet Union.

'Quantum diplomacy'

In the course of working together, said Shultz, he and Drell coined the term "quantum diplomacy" - a reaction to the impetuous nature of the beast. "Sid said, 'As soon as you observe something in physics it changes, so it's very hard to really observe something,'" Shultz recalled. "I said, 'Boy, in diplomacy, you put a TV camera around something, it's not the same.'"

Shultz was asked to discuss a prominent example of such fragile diplomacy - the 1986 Reykjavik negotiations between Reagan and Secretary-General Mikhail Gorbachev.

"The Reykjavik meeting came as a suggestion from the Soviet side," Shultz said. "We didn't know quite what to expect from the Soviet delegation. … Right off the bat in the morning, Gorbachev read aloud a whole series of proposals that essentially were granting all the proposals we'd made … practically going to zero on INF weapons, cutting strategic weapons in half - those were all our proposals that they had before resisted."

The summit eventually fell short of the mutually desired goal of total elimination of nuclear explosive devices within a 10-year period, but established a precedent for the types of concessions that the Soviets and Americans were willing to make and eventually resulted in the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

Shultz and Reagan continued to prioritize nuclear weapons reduction as an agenda point.

"What's the biggest threat to the United States?" they asked one another. "We both thought, not since the British burned the White House in 1814 has anything threatened our security like a ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead on the end of it," said Shultz. "And if we could get rid of them, we'd be a much safer country. And for that matter, if we could get rid of them entirely, it would be a safer world."

Faced political opposition

The idea was met with intense political opposition. Shultz and Reagan thought Gorbachev could be reasoned with, but many remained unconvinced.

"As we worked with the Soviet Union, and as we started negotiating, there was a lot of opposition to that," said Shultz. He remembered "saying to my delegation, 'This is a different Soviet leader than anybody we have ever encountered before. He's quicker, he's smarter, he's much more agile, and he's formidable, but you can have a conversation with him, he'll listen to you.' So I thought, and President Reagan thought, that change was possible in the Soviet Union."

The CIA, the Defense Department, former President Richard Nixon and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were among the opposition. "After all, they were the authors of détente," Shultz explained. "Détente was, 'We're here, they're there, that's life - the name of the game is peaceful coexistence.' We rejected détente."

The Reagan era's ambitious plans for disarmament were left at an impasse, and global nuclear threats outlived the end of the Cold War. Drell noted that the world left in its wake poses a very different set of challenges. Still, he has not wavered in his support for a program to totally eliminate nuclear weapons. A viable process for nuclear disarmament, he explained, would ideally incorporate provisions for transparency and cooperative verification, as was achieved in the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) between the United States and Russia, ratified in 1991.

"The technical realities, the political realities and the urgency have made this a much more compelling case," said Drell.

Well-timed discussion

The timing of Monday's discussion could not have been more pertinent, as the U.S. Senate awaits a renewed arms treaty with Russia. If ratified, the treaty would introduce a new round of reductions - a move that has attracted criticism from Senate Republicans supporting a modernization plan for existing U.S. nuclear warheads.

Taubman, a consulting professor at CISAC, questioned whether President Obama's lofty plans for disarmament can muster the political momentum needed to translate thought into action, both domestically and in the United Nations. The support of the U.S. military-industrial complex was of particular concern.

Shultz said he believed that the Senate would ratify a new START if robust provisions for verification of disarmament procedures were integrated into its program, and emphasized the need to adopt a "hardboiled" diplomatic policy with Iran. Drell added that budget concerns would need to be carefully weighed. The critical next step, they agreed, is implementation.

"In a sense the battle of rhetoric has been won," said Shultz. "Now the battle of action is in front of you. What are you going to do about Iran? What are you going to do about North Korea?"

In light of these uncertainties, new questions were raised: How would a non-nuclear deterrence regime function? How could it?

Said Drell: "Trying to establish stability when you have knowledge and can reconstitute [nuclear weapons] is what you're going to have to work with."

Aimee Miles is an intern at the Stanford News Service.