Radiologists as artists: Critics love mummy scans

It's definitely science, but is it art?

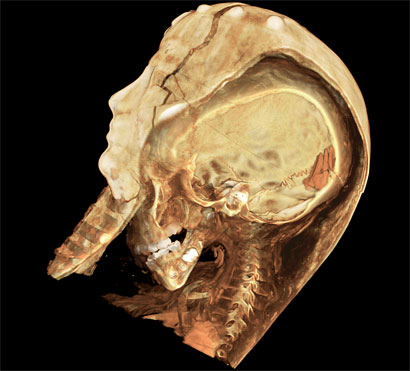

The National Science Foundation and Science magazine apparently think so. They have deemed an image of a 2,000-year-old child mummy scanned at Stanford worthy of their highest artistic honor: first place in photography in their Science and Engineering Visualization Challenge.

Last May, officials from the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum & Planetarium in San Jose carefully transported one of their mummies, a 75-year resident of the museum, to the basement of the medical school's Grant Building. There it underwent some 60,000 scans with a specialized CT scanner that has an arm that rotates around the patient—or mummy—from many angles.

The scans revealed the most detailed images of any mummy to date, with slices about the thickness of a business card, according to one of the team leaders, Rebecca Fahrig, PhD, associate professor of radiology. The team could see the healthy-looking skeleton of a 4- or 5-year-old girl, who showed no signs of trauma or lengthy illness. The girl, who has been dubbed Sherit, ancient Egyptian for "little one," most likely died of an infectious disease. They could also see that her body was draped in linen and adorned with jewelry wrapped in gilded cartonnage, all suggesting a life of wealth and privilege.

The NSF and Science created the Science and Engineering Visualization Challenge to celebrate that role that imagery plays in connecting scientists with the public and in nurturing community interest in research developments. Their call for entries says, "In an increasingly graphics-oriented culture, where people acquire the majority of their news from TV and the World Wide Web, a story without a vivid and intriguing image is often no story at all."

More than just a pretty picture, the mummy images not only bring to light some of the questions about the mummy herself, but also highlight how new developments in imaging technology can benefit people living today—from clinical diagnosis to surgical planning to virtual autopsies. Paul Brown, DDS, a researcher at the biocomputation center and organizer of the mummy team at Stanford, said the scanner used for Sherit is "the future of medical imaging." In addition to Brown and Fahrig, the team acknowledged for the photography honor are Robert Cheng, MS, science and engineering associate at the School of Medicine, and Christof Reinhart of Volume Graphics, a software company in Mountain View, Calif.

The mummy image was a clear winner, despite the fact that CT scanning and computer imaging, rather than traditional photography, produced the images, said one of the judges of the competition. She said the mummy photo showed how "the definition of photography in science has expanded."

The same judge also described the image as "stunningly beautiful." Beauty is definitely in the eye of the beholder, or at least the eyes of the judges. The second runner-up for photography: A Cuban banana cockroach.

Share This Story