Nearly every day in this country, at least one talk is being given. How many are being heard is another matter.

Stanford instructor Dan Klein, who teaches acting and improvisation — and how to give great talks — recently asked the 2013 Knight Fellows what things got in the way of them enjoying a talk. Their list included a speaker who:

- Recites or reads his talk

- Doesn’t make eye contact, makes eye contact with just one person, or tries to make eye contact with too many people

- Speaks in a monotone, speaks with no pauses, or speaks too fast or too slow

- Presents content that doesn’t match audience needs

- Doesn’t have a point

- Delivers the talk without any physical gestures at all

Meeting audience needs

Klein said the simple solution for anyone planning to give a talk is to prepare, with three essential elements in mind: content, delivery and psychological state. Being successful is more than just being heard. It’s moving people to action, he said.

So one of the first things you want to do to prepare your talk is think about what outcome you want. Do you want your audience to donate time or money, modify their behavior or think differently about something? The next step is pinning that outcome to the needs of your audience. Why should they do what you are advocating? What will they get out of it? Will it help them do their jobs better, for example?

This is also where the psychological component comes in. What emotions might your audience have toward the subject? What do you want them to feel? Fear? Hope? It’s best to start out with a positive, but blending in a little fear doesn’t hurt, Klein said, such as: “‘if you don’t stop eating cheeseburgers for every meal, you’re increasing your risk of a heart attack.’” Once you answer these questions, you can start structuring your talk with a beginning, an overview, a middle and an end.

A winning structure

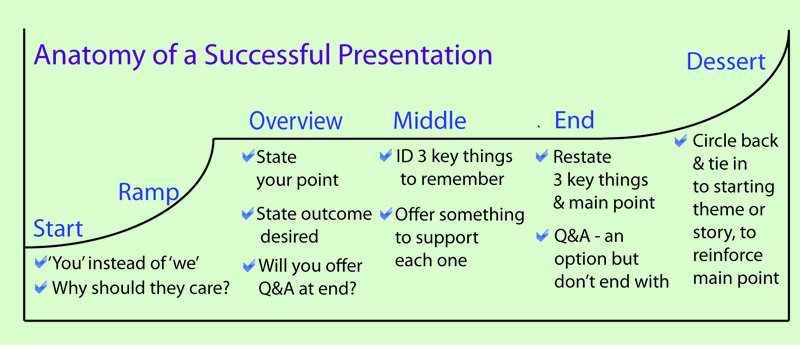

Pay special attention to the beginning and ending, Klein said. “If you don’t get their attention in the beginning, they may not follow you to the end.” Statistically speaking, the best measure of success is what they remember at the end. “The ending is at least half the game.”

The Start: This is your chance to grab audience attention and ramp them up to hear more. You can start with something surprising, a great joke, or a story. But the best is something that shows them how your topic relates to them and why they should care. “It’s got to be about the audience,” said Klein. Speakers sometimes address an audience as “we” in order to relate, but even more pointed, he said, is to address them as “You.”

The Overview: Let them know what the main point of your talk is, and what you hope to accomplish — that is, what you hope to motivate them to do.

The Middle: Identify three key things you want them to know and provide statistics, anecdotes or other information to back each of them up.

The End: Restate your main point and the three key things you want them to remember. At this point you could open your talk up to a question and answer session. But don’t let your talk end with the last question. You never know when it could be a mood killer. You want them to go out the door feeling upbeat and inspired. So, give them some:

Dessert: Bring it back to whatever you started with, whether an anecdote or story or statistics. Leave some interesting element to share after the end. As Klein said: ”The key to the end is that you can have the summary, and the Q&A, but don’t end there. Dessert is the very last thing, and it reinforces the main point.”