Stanford students bring much-needed health care to rural Guatemala

For more than 30 years, Stanford School of Medicine Professor Paul Wise has traveled regularly to rural Guatemala to provide health care for people who desperately need it. He brings with him Stanford medical students and undergraduates interested in helping the residents of San Lucas Tolimán.

Stanford News Service writer Adam Gorlick is in San Lucas with the Stanford team. He will post periodic updates on the program, the people of San Lucas and the experiences of the students who have shifted abruptly from Palo Alto to a small town in southwestern Guatemala.

Stanford biology major Anand Habib crosses a flooded road on his way back to San Lucas Tolimán.

A short-lived return to normalcy in rain-battered Guatemala

SAN LUCAS TOLIMÁN, Guatemala - The children of San Lucas had nice enough weather to return to school on Thursday.

They had been home since early June, ever since their classrooms were turned into emergency shelters for the families flooded out of their houses by the tropical storms passing over this part of Guatemala.

But today promised to be warm and dry, with just a few clouds hanging in an otherwise sunny sky. The flooded homes had dried out, and the town's school kids donned uniforms, backpacks and smiles as they loaded into buses or walked back to school.

The group from Stanford was thankful for the break in the weather as well. It had rained since they arrived here Sunday, and the dampness and gloom were becoming tiresome. Some decided to leave their rain gear behind before heading to Panimaquip to provide some basic medical care and interview women about maternal health care in the poor hilltop village about 20 minutes from San Lucas.

The early part of the day was a success: Paul Wise and two medical students saw about 50 patients at a makeshift clinic they set up with the help and invitation of local health care promoters. Kate Leonard, a Palo Alto pediatrician who spent a year living and working in Guatemala, joined three Stanford undergrads in a chat with a few women about the care they receive when pregnant.

The clouds returned quickly. Just as our driver, Ricardo, came to pick us up, a thunderstorm cracked overhead and the rain began to pour.

We piled into Ricardo's Ford pickup and made it as far as the bottom of the hill leading out of the village. Getting in our way was a flood, cutting us off from higher ground and the road back home. Crossing it seemed like a bad idea.

We poured out of the flatbed and headed back up the hill for shelter. Meanwhile, Ricardo managed what seemed to be the impossible. He gunned the engine and crossed the rushing flood. When the rain slowed a bit and we made it back down the hill, we had no choice but to make the water crossing by foot. Those of us who remembered our rain gear were now on a level playing field with those who didn't. There was no way around being soaked.

A few miles later, we were in the same predicament. Only this time, so were 10 other vehicles. Trucks, sedans and school buses were stuck on either side of another river that was rushing across a dip in the road.

More waiting. More hesitation. Much determination. Only one car turned around and went back the way it came. Everyone else was going to get across - or get washed away trying.

Passengers abandoned their vehicles, leaving it to the drivers to say a prayer and hit the gas. Ricardo aimed his Ford with its non-functioning 4-wheel drive at the washed-out gully. The truck, bouncing through more than bumper-deep water, was pounded by rolling rocks along the way but made it to higher ground.

Meanwhile, someone got a rope. And someone threw it from one side of the water to someone on the other. The setup for a tug-of-war became a pull for cooperation. With men on both sides yanking the rope tight, people used it as a guide to cross the water and join their vehicles on the other side.

Women carrying babies. Guatemalan day laborers. Stanford academics. And those kids who finally had their first day back at school and were now trying to get home. Everyone was drenched and cold - but thankful to finally be on the other side of the flood.

Tuning in to the sounds of life in San Lucas

SAN LUCAS TOLIMÁN, Guatemala - The first sound of the day you'll hear in San Lucas Tolimán usually comes from the roosters.

Their throaty, cackling calls quickly wake the town's dogs. Their barking chorus comes from the streets they've prowled all night, the roofs they've paced and the stoops where they've slept. But it likely quiets down every six months or so when government workers set traps to poison the strays.

Following the dogs are the sounds that can't be made without the people of San Lucas. Diesel-powered mills start with a cough and roar into a clack-clack-clacking as they grind kernels of corn into mush. Women balance bucketfuls of the stuff on their heads, carrying it away to pound and stretch and press into tortillas.

Little storefronts open and their owners call out to passersby. If the rain stops these days, children come out to play.

Tuc-tucs - the three-wheeled taxis that look like they'll topple in the next turn but somehow manage to plow through flooded roads and defy the steepness of hills - putter along the streets.

Then there's the sound of those who don't live here but come to this impoverished place to help.

The doctors talk about using their medical expertise to improve health care.

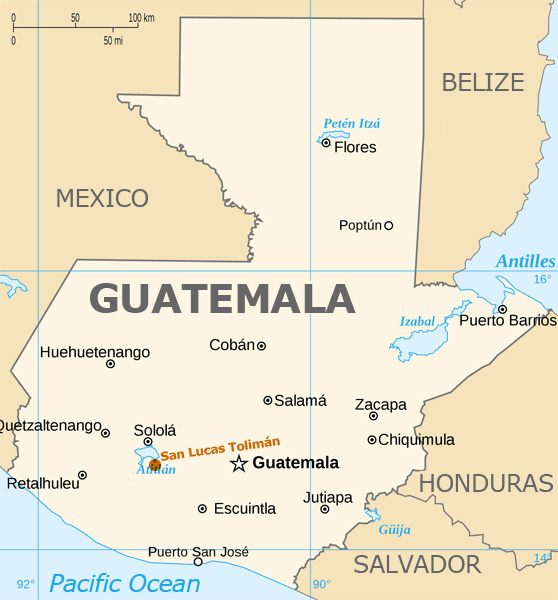

The Stanford team will provide health care to rural communities surrounding San Lucas Tolimán. (click to enlarge)

The students discuss their goals and ideas and passions for correcting some of the social injustices that breed poverty and oppression.

The religious pray that their faith - and their own hard work - can help lessen some of the suffering in a country where less than 2 percent of the people own more than 60 percent of the land.

At some point during the day, many of the volunteers will wander into the dining hall of the San Lucas Mission for a meal, a conversation or a cup of coffee grown on a nearby plantation. The Rev. Gregory Schaeffer has run the mission for the past five decades, co-coordinating some relief efforts and raising money for the people here.

The visitors swap stories of what they've been doing. Some talk about the possibility of coming back. Others sound like they can't wait to go home. A few are like Stanford pediatrics Professor Paul Wise, who can't stay away.

"I fell in love with the place and the people" is what he says when you ask him about his first visit to San Lucas in 1970. "I expect that I'll continue to be working down here until I can't."

The groups of do-gooders go about their separate ways. They stay near the mission, fan into the streets of San Lucas, or - like Wise and the Stanford students here with him for a few weeks - get rides into the neighboring villages where the poverty only increases and the need for help is more dire.

The days in San Lucas wind down as the storefronts close and the people return home. The volunteers return to their hotels or the families they're staying with. And the last dogs bark in the dark, giving way to a few hours of quiet before the roosters wake again.

June 29, 2010

Treating the diseases of poverty

SAN JUAN, Guatemala - The gringo doctor came to town Tuesday, and the people of San Juan were waiting.

Before Stanford pediatrics Professor Paul Wise turns the metal-sided schoolhouse into a makeshift clinic, patients are streaming in. Wise is joined by two Stanford medical school students - Patricia Foo and Jake Rosenberg - there to help diagnose the health problems of people in this poor, rural village outside of San Lucas Tolimán.

Medical school student Jake Rosenberg examines a six-month old diagnosed with pneumonia.

The three set up their own exam areas: a desk and a few chairs. Each station is spaced just a few paces apart, and Wise double-checks the diagnoses made by the students. They're here to learn as much as they are here to help, still not far enough along in their careers to make final calls on health care.

The chairs fill quickly.

Here comes one young woman with a 6-month-old held close in a sling. The baby boy is scheduled for surgery to repair his cleft lip, but that's set to happen in a few months when another American doctor comes to this area to operate. Today, his problem is a cough - a tiny hack from a tiny body - muffled when he turns his face into his mother's bosom.

Wise presses his stethoscope against the child's back. Again, against his chest.

Pneumonia.

"This is dangerous," Wise says. "Six months with pneumonia is dangerous."

He walks over to a corner of the spontaneous clinic where Belinda Byrne of Stanford's Freeman Spogli Institute has arranged basic medicines donated by American doctors: painkillers, antibiotics, eye drops, anti-diarrheals. Wise gets what he needs and hands it to the boy's mother. While he's at it, he hands her a tube of cream to treat the baby's scabies.

Paul Wise examines a child in San Juan as medical school student Patricia Foo looks on.

Then Wise rubs hand sanitizer between his palms and moves on to his next patient. And the next. And the next. And the next.

Most of the children are suffering from easily preventable problems and sicknesses that can be treated with over-the-counter drugs found in any American pharmacy. Diarrhea. Worms. Scabies.

But in San Juan, people often have to wait for an Advil to be donated. Then they have to wait for it to reach them.

"It takes the students about three minutes to figure out that the health problems we're seeing are diseases of poverty," Wise says. "It's profound material deprivation, and in many cases political oppression, that generates the health problems we face here."

One child comes in with a respiratory problem, and Wise teaches Foo how to find it by placing her stethoscope on just the right spot on the girl's back.

"It sounds like a wheezing and popping - like bubble wrap when you squeeze it," Wise tells Foo.

Wise and the students work closely with a couple of health care promoters - people from the village trained to help the families in their community get the care they need, even if it means waiting for a foreign doctor to come through the area a few times a year.

Keeping tabs on the sick, the promoters make sure they take their medicine as prescribed. And they follow up to see if they're getting better. That medical history is jotted down on index cards, and Wise, Foo and Rosenberg review each of them before asking their patients any questions.

By the time the gringos leave for the day, Wise figures they've seen about 50 people. But they aren't done - the rain that's beaten this region with floods, mudslides and washed out roads for the past month returns around 1 p.m. If they don't leave now, the roads will be impassable.

They'll be back tomorrow.

June 29, 2010

Remnants of lives washed away

SAN LUCAS TOLIMÁN, Guatemala - The rains let up Tuesday morning here in San Lucas Tolimán. Long enough at least for a tour of the damage all the water has done.

Ten houses at the bottom of a hillside were washed away in the downpours that hit this area about four weeks ago. All that's left are the reminders that lives were lived here: pieces of metal roofs and cinderblock walls, food wrappers, pieces of a baby swing.

One husband and father who didn't trust the banks packed his family's savings into the walls of his home. When the flood came, he had only enough time to get his wife and children to safety. Their savings were washed away, now buried in thick mud.

Some lost even more. Ten people in San Lucas died in the flooding.

There's no chance the houses will be rebuilt anytime soon, but there are glimmers that things will return. Saplings have been planted among the debris of the washed-away homes, in the hope that their roots will strengthen the soil.

June 28, 2010

A rain-soaked welcome to Guatemala

Bianca Argueza grabs a bag of vitamins at San Lucas' hospital. The human biology major and FSI intern will help deliver those and other medications to the rural villages around San Lucas, Guatemala.

SAN LUCAS TOLIMÁN, Guatemala - Driving the road from Guatemala City to San Lucas Tolimán takes nerve. Heavy rains washed away portions of the paved two-way lane a few weeks ago. The debris from mudslides has created a tougher obstacle course for drivers already forced to weave around potholes, caution signs and the occasional dog or pedestrian that gets in the way on the curvy path leading up, up and up to Guatemala's western highlands.

Once there, the rains start again. Drizzling at first, then cascading over the metal roofs of San Lucas' buildings in a quick thunderstorm. The two volcanoes overlooking this city are cloaked in fog, and low clouds hang over the soaked coffee plantations and the yawning Lake Atitlán. Word has it that water levels are rising too high and too fast, and some people are evacuating their homes. The weather forecast calls for steady rains over the next two days.

It's been a wet and road-weary welcome for the Stanford students who arrived last weekend to provide health care and study the medical services available to residents of this poverty-stricken city and its surrounding villages.

Under the guidance of Stanford pediatrics Professor Paul Wise, the group of medical students, as well as undergraduates chosen by the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, are seeing firsthand what it takes to provide medical care to the rural poor in a developing country wracked by decades of civil war, political corruption and the violence of a growing drug trade.

For Wise, the trip to San Lucas is an extension of the work he's been doing in Guatemala for more than 30 years. And it's the basis of Children in Crisis, a program he started this past year to marry Stanford's medical research with the university's expertise in international studies to provide health care to the world's most vulnerable patients: children living in politically unstable nations.

Starting on Tuesday, Wise and the students will head out to some of the 15 rural communities surrounding San Lucas. They stocked up for the trip with medicine - much of it donated by American doctors - at the town's hospital, supported by the San Lucas Mission, a Roman Catholic parish.

The maladies they'll be treating are some of the most common - colds, stomach viruses, diarrhea, asthma, malnutrition and skin conditions. In developed countries, those problems can be easily fixed or avoided with regular medical care or a quick trip to a doctor.

But around San Lucas and much of Guatemala, medical services and health care providers are sparse. The Stanford group is teaming up with some of the local promotores, the 30 volunteers from the neighboring villages who encourage people to seek medical care and help them get the medical attention they need.

The students plan to blog every day - as Internet connections allow - on their experiences, impressions and challenges of working in the area during the next two weeks. Their posts can be found at https://intheworld.stanford.edu.

Share This Story